We thirsty seniors are entitled to specially priced soft drinks at Taco Bell for twenty-five cents. But I’m an unentitled junior when it comes to prayer. I took a course or two in religion as an undergraduate and was remotely aware of the National Day of Prayer, the annual observance in May designated by the U.S. Congress when people are asked to “turn to God in prayer and meditation.” But I frankly never gave prayer any extended thought until recently. It seemed logical to go on-line and see if I had the remotest idea what a prayer actually was.

We thirsty seniors are entitled to specially priced soft drinks at Taco Bell for twenty-five cents. But I’m an unentitled junior when it comes to prayer. I took a course or two in religion as an undergraduate and was remotely aware of the National Day of Prayer, the annual observance in May designated by the U.S. Congress when people are asked to “turn to God in prayer and meditation.” But I frankly never gave prayer any extended thought until recently. It seemed logical to go on-line and see if I had the remotest idea what a prayer actually was.

Merriam Webster defines prayer as “an address (as a petition) to God or a god in word or thought” such as a prayer for the success of a voyage, or, similarly, “an earnest request or wish.” I suppose some of us are just as familiar on a day to basis with the notion of prayer as a slight chance, as in, ‘he hasn’t got a prayer of making that shot.’

So what happened to get me thinking about prayer? Actually it was a combination of two ingredients that catalyzed each other. Hoagy Carmichael wrote a lovely song in 1941, “Skylark.” Johnny Mercer’s lyrics include lines that have haunted me:

…Skylark

I don’t know if you can find these things

But my heart is riding on your wings

So if you see them anywhere

Won’t you lead me there…

Those words swirled in my mind as I thought about the heart rending story of the Florida boys who went missing in the Atlantic this summer when one of their fishing trips, carried out on a 19-foot boat, collided with a storm. Perry Cohen and Austin Stephanos were fast friends. Fishing buddies. “Candles and lanterns lit the sky,” we read, as hundreds joined the vigil.

These kind folks made it clear that they hadn’t given up the fervent hope of finding the boys. The U.S. Coast Guard did what it is justly famous for, putting on a full court nautical press across an area about the size of Kentucky. Captain Mark Fedor said it was a “gut wrenching decision” whether to suspend their search after days of intense work. After five days they believed the boys’ chances of surviving in the open water were very slim. Perhaps by then they ‘didn’t have a prayer.’ Or did they? The world witnesses remarkable events from time to time and human endurance is legendary. Some men survived the horrible Bataan death march executed by the Japanese in WWII, after all. Surely that was “impossible.”

Perhaps in that spirit, Pamela Cohen, Perry’s mother, said “We are 100% committed to finding and rescuing those boys, as is the Coast Guard, and we will not stop until we get them back home with us…We just feel very, very confident that they will be able to stick through this. They know that we’re coming for them and we will get them,” she said. A privately funded search followed the Coast Guard’s effort as a community of hope and love refused to give up on and continued to pray for the 14-year olds.

Clearly one can pray forward. I’ve been wondering if you can also pray backward. Historian David McCullough got me thinking about this as I considered his description of early Americans fighting for independence:

According to the official roster, the Connecticut brigade commanded by Colonel William Douglas numbered 1,500 men. But a third or more were sick, and only about half of those fit for duty… Many were the greenest of green American troops, farm boys who had joined the ranks only the week before. Some who had no muskets carried homemade pikes fashioned from scythe blades fixed to the end of poles…

As Frederick Mackenzie recorded, the British were astonished to find how many of the American prisoners were less than fifteen, or old men, all “indifferently clothed,” filthy, and without shoes. “Their odd figures frequently excited the laughter of our soldiers.” (David McCullough, “1776”; NY: Simon & Schuster, 2005)

Pondering our forebears, I found myself wanting (was it praying?) to be able to step back in time with a USO-style relief effort. Provide them some medical care and bring on the medics and corpsmen. Get them some nourishing food and something to drink, maybe some milk or Gatorade. While we’re at it, shuffle them into warm taverns with live music… the wonderful bar band Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes came to mind. I’d volunteer to be emcee and help to triage those who are so relieved and comforted that they are rendered teary or speechless. (And yes, get them some decent shoes and weapons!)

Returning to the present, it strikes me that praying is a fine act, but reaching out and touching others is often more powerful. Everyday acts of kindness abound and yet they are often drowned out in the 24-hour cycle of disaster news. A Florida police officer got me thinking about this again. Amidst all the focus on abominable acts of police violence there are countless acts of humanity performed by police across the country.

Oscala’s Sergeant Erica Hay came upon a homeless man and bought him breakfast from the Dunkin Doughnuts she had stopped at to get herself something to eat. Her kind, humble heart shone like a brass ring as she noted “I didn’t have anyone else to eat breakfast with that morning either…he was gracious enough to eat with me.” Right there on the sidewalk where she found him. Could a breakfast sandwich and a cup of coffee ever have tasted any better?

Now back to another transformative event, this time the Civil War. It is hard to read or write about this horrible time without wiping away tears. I just finished Brooks Simpson’s seminal work on General Grant and dwelled on this passage:

“Accompanying [General Benjamin F.] Butler’s two corps north of the James, Grant rode forward to examine a line of works captured by [ardent abolitionist General] William Birney’s brigade of black soldiers. ‘As soon as Grant was known to be approaching,’ one officer later recalled, ‘every man was on his feet & quiet, breathless quiet, prevailed. A cheer could never express what we felt.’” (Brooks Simpson: Ulysses S. Grant; New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000)

If at least some of these men weren’t praying I need to go back to square one. Brooks makes a strong case that the real Grant was a more compassionate, sober war leader than he is commonly credited as; much more prescient, more human. A little dusty and disheveled, yes, but a real person with real compassion. And no wonder his men were sometimes rendered silent.

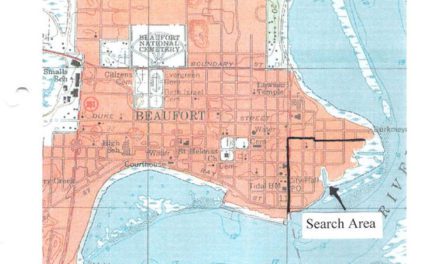

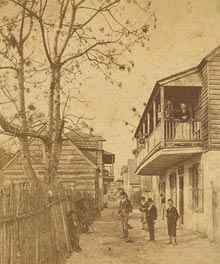

And… back to the present. We just returned from Charleston, one of the most charming cities on earth with some of the loveliest people. Visiting the Emanuel AME Church on Calhoun Street as a silent drizzle cast its spell on our way to a fabulous dinner with friends took my breath away. The flowers, messages, pictures of the slain against the plainly elegant exterior of the building. The thoughts and hopes of so many fine citizens. No doubt many of them pray when they visit this sacred place. Maybe we all do in our own way, even me. Pray tell.

Jack Sparacino earned a Ph.D. in psychology from The University of Chicago and later worked as a post-doctoral research fellow at Ohio State University in the business school. He is retired from United Technologies Corporation, Sikorsky Aircraft division and lives with his wife Jane and their two Yorkies on Saint Helena Island. He tries his best to catch a lot of fish, especially when sons Jack and Greg visit, stay off ladders, read only great books and write clearly. Sometimes he succeeds.