Thoughts on Veterans Day

Thoughts on Veterans Day

Veterans Day is a landmark observation, the official day in America that honors those who have served in our armed forces across all wars. A federal holiday, it falls on November 11. First designated Armistice Day by President Wilson, it marked the end of horrific World War I and served as a permanent national remembrance of our service veterans. Congress renamed Armistice Day as Veterans Day in 1954. Few holidays are as profound.

Veterans Day is far more than just another day off from work or school. November 11 commemorates many of the finest Americans who ever lived and their immeasurable contributions to defending our nation worldwide. Having studied about our veterans and spoken with many, I wanted to commit some associated thoughts and feelings to paper. Even for someone who loves to write, it was at first a difficult but mostly humbling job.

Where on earth to start? The initial exploration of the American West—a war of sorts– came to mind, and the idea took off like wildfire when I dove into the timelessly inspirational book by Stephen Ambrose on the Lewis and Clark expedition, Undaunted Courage (Simon & Schuster, 1996). In their roles as America’s premier explorers, Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and William Clark (1770-1838) served as captains in the U.S. Army, commissioned by President Jefferson to chart an all-water route to the Pacific; and along the way, map the terrain and essentially absorb and record all there was to learn about the country’s wildlife, geography, and Native Americans.

Lewis and Clark were seldom surpassed as military leaders: smart, fiercely dedicated to their men, resourceful, disciplined. And tough as rawhide. The thirty or so of them plus the irreplaceable young Shoshone woman, Sacagawea, and Clark’s slave York made a few tactical mistakes in dealing with various Indian tribes, persistent diseases and terrain obstacles, but it is hard to imagine any more relentless and ultimately successful soldiers breaking the back of a nearly impossible mission.

Ambrose’s sweeping history benefits from irresistible details that bring an expedition that began in 1803 to vibrant life for any reader. One small example: the physical labors, including paddling cumbersome boats thousands of miles, were so extreme that the soldiers often ate up to nine pounds of meat per day per man (in addition to their basic stores and whatever they could gather along the trail) and often still remained hungry.

Ambrose’s prose is lyrical, stirring, and inspiring. “The captains expected to be gone two years, perhaps more. In all that time, in whatever lay ahead of them, whatever decisions had to be made, they would receive no guidance from their superiors. This was an independent command, such as the U.S. Army had not previously seen and never would again.” They were on their own, come hell or high water… and both came in full force. Along the way they made history. Upon finally reaching the west coast and needing to determine where to spend the winter, they invoked democracy: “This was the first vote ever held in the Pacific Northwest. It was the first time in American history that a black slave [York] had voted, the first time a woman [Sacagawea] had voted.”

Fast forward 138 years to WWII, October 25, 1944 off the island of Samar in the Philippines. Naval historian extraordinaire James Hornfischer plumbs the scholarly and human depths of perhaps the most hellish battle ever fought by our sailors, which far too few of them survived. The book is The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors: The Extraordinary World War II Story of the U.S. Navy’s Finest Hour (Bantam, 2004).

Hornfischer’s account is brilliantly researched and written, uplifting and heartrending. The story of the “Taffy 3” sailors (their 13 ships were commanded by Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague as part of “MacArthur’s Navy”) who found themselves in the gun sights of a vastly superior Japanese force but fought back with everything they had brings tears to one’s eyes. No one need wonder why this cohort of young Americans who fought through the horrors of WWII is called “the greatest generation.” For anyone interested in naval history, leadership, teamwork, or warfighting technology, this book is stellar. Americans today are the beneficiaries of these sailors who all but rewrote the standards of courage and bravery under the most blisteringly hostile conditions imaginable. They were vastly outgunned and initially outmaneuvered but ultimately succeeded in turning back the enemy and rendering Japan’s once mighty navy all but irrelevant.

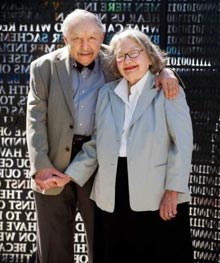

I make no secret of my reverence for American soldiers, sailors and airmen. We lose veterans every day, all too often before their time. One of these veterans, a dear friend of our family, made it a very long way after his years in the service. He recently passed away at age 90. His name is Arthur H. White, a scholar, public opinion pollster, social activist, gentleman, fine husband to Vivien. A brilliant, tireless mensch. (Pictured above, with wife Vivien.)

Arthur was my wife’s mentor at Yankelovich, Skelly & White (YSW; she was Jane Hill then), recognizing her talents in helping to run a vibrant organization. Among his many accomplishments, he co-founded YSW and helped to launch RIF, “Reading is Fundamental.”

Arthur was born into the surging tide of American industrial and cultural might in 1924. What fun to glance back to when:

– Calvin (“Silent Cal”) Coolidge was president

– IBM was founded

– A dozen eggs, loaf of bread and a pound of coffee cost about $1 (in total)

– The first regular airmail services started in the U.S.

Like so many in his generation, Arthur White was off and running as he stepped away from his U.S. Army Air Force Service in WWII and went to college on the G.I. Bill. His social and work circles encompassed U.S. presidents, major executives, and philanthropic and educational leaders. His nearly countless followers and colleagues were out to change the world for the better. As Joseph Carbone wrote in Arthur’s Stamford Advocate obituary, “His network of friends and associates served as a corps that was steadfastly committed to ensure that what Barbara Jordan described as the “America promised” was a promise to all, not just some.”

Arthur also founded Jobs for the Future (JFF), a workforce-education think tank based in Boston. As Mr. Carbone noted, “It has grown volumes since Arthur created it but never strayed from the principles he espoused. They recruit the best and the brightest, those that find virtue in imagination and view change in profound terms. Their respect for intellectual freedom and their pursuit of solutions as a matter of duty personify an ethos that has made JFF an American treasure.”

Like many others, I never had the chance to spend enough time with Arthur. I’ll remember his infectious smile, his churning enthusiasm for whatever projects he was engaged in, his delightful charm and sense of humor. Even at 90, he was gone too soon. Another glorious citizen we can all think about on Veterans Day.

Our wonderful veterans. They are all around us, and like the air we breathe, too easily taken for granted. November 11 is more than their day. It is their legacy.