Designed by an iconic American architect, restored by a legendary Hollywood producer, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Yemassee plantation remains a work in progress. Mark Shaffer talks to the architect’s grandson – and the lead architect in the restoration process – Eric Lloyd Wright.

Designed by an iconic American architect, restored by a legendary Hollywood producer, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Yemassee plantation remains a work in progress. Mark Shaffer talks to the architect’s grandson – and the lead architect in the restoration process – Eric Lloyd Wright.

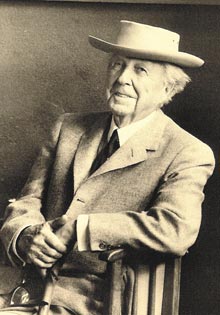

“Every great architect is – necessarily – a great poet. He must be a great original interpreter of his time, his day, his age.”

– Frank Lloyd Wright, 1867-1959

More than a half-century after his death, the great American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright’s status as the great original interpreter of his time – and beyond – is transcendent. Time, circumstance and the wrecking ball have whittled away at the great man’s legacy, raising the value – both economical and cultural – of what remains. Thanks to the early efforts of the Beaufort County Open Land Trust, one of Wright’s hidden treasures has been lovingly and meticulously rescued from certain oblivion in a story made for the movies. Fittingly, the central character is something of a legend in the film business. Joel Silver is among Hollywood’s elite producers, known for blockbuster franchise titles like Lethal Weapon, Die Hard, The Matrix, and Sherlock Holmes. The man knows his way around a hit action flick – he practically invented the genre – but he is also a renowned and passionate collector all things Frank Lloyd Wright. The acquisition of Auldbrass – Wright’s only Southern plantation – was like buying a piece of architectural mythology. One that needed a hell of a lot of work.

More than a half-century after his death, the great American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright’s status as the great original interpreter of his time – and beyond – is transcendent. Time, circumstance and the wrecking ball have whittled away at the great man’s legacy, raising the value – both economical and cultural – of what remains. Thanks to the early efforts of the Beaufort County Open Land Trust, one of Wright’s hidden treasures has been lovingly and meticulously rescued from certain oblivion in a story made for the movies. Fittingly, the central character is something of a legend in the film business. Joel Silver is among Hollywood’s elite producers, known for blockbuster franchise titles like Lethal Weapon, Die Hard, The Matrix, and Sherlock Holmes. The man knows his way around a hit action flick – he practically invented the genre – but he is also a renowned and passionate collector all things Frank Lloyd Wright. The acquisition of Auldbrass – Wright’s only Southern plantation – was like buying a piece of architectural mythology. One that needed a hell of a lot of work.

Commissioned in 1939 by industrial consultant C. Leigh Stevens, the beautifully restored property occupies 315 acres near Yemassee along the Combahee River, complete with a herd of zebras and other exotic creatures, including the occasional movie star. Today the estate is a working farm and a treasured retreat for the Silver family. Silver’s known for showing up at nearby Harold’s Country Club with a famous guest to soak up an evening of local culture.

Every other year the Silvers open Auldbrass to the public as part of the original purchase agreement through the Beaufort County Open Land Trust. These highly anticipated tours represent the biggest single fundraising event for the OLT and go to support vital land preservation efforts.

“Over the years Mr. Silver’s been extremely generous by allowing us to hold this fundraiser with all the proceeds going to the Land Trust,” says OLT Executive Director, Patty Kennedy. “Part of that is that I think he just supports the mission of the Land Trust.”

The tour weekend requires a huge effort begun a full year in advance and up to 150 volunteers, says Kennedy. “We don’t want to miss a trick. We want to be as respectful as possible to the house, the grounds and the family’s privacy.”

The tour weekend requires a huge effort begun a full year in advance and up to 150 volunteers, says Kennedy. “We don’t want to miss a trick. We want to be as respectful as possible to the house, the grounds and the family’s privacy.”

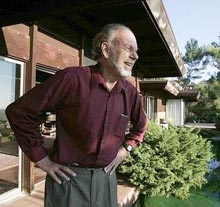

Tickets to this year’s Auldbrass tours are long gone. If you don’t already have one in hand your next chance is November 2014. However, there’s still a chance to learn more about this remarkable Lowcountry estate from the grandson of the man who designed it and the lead architect on the restoration. Eric Lloyd Wright will conduct a lecture on Auldbrass and the restoration process at USCB’s Performing Arts Center as part of the weekend event.

“When we reached out to Eric earlier this year and he agreed we were thrilled,” says Kennedy. “I think he can speak not only to the renovation and the house but to his grandfather’s vision and perspective. And, of course, Eric is a star in his own right.”

Eric Lloyd Wright was already well acquainted with Joel Silver when word reached the West Coast that Auldbrass was for sale. Like the inexorable John McClane in his blockbuster hit Die Hard, Silver undertook the daunting task of restoring Auldbrass with a yippee ki yay sort of attitude. Restoration began in earnest in 1988 and has never really ceased. Silver likens the process to “painting with a checkbook.” Eric Lloyd Wright was there from the very beginning. I spoke to him by phone from his Malibu studio.

A CONVERSATION WITH ERIC LLOYD WRIGHT

Mark Shaffer: How did you become involved with Auldbrass?

Mark Shaffer: How did you become involved with Auldbrass?

Eric Lloyd Wright: I was the restoration architect for Joel Silver on a building he owned in Los Angeles that was designed by my grandfather. While we were finishing up, Joel got a call from the Beaufort County Open Land Trust saying they had acquired the estate of Auldbrass from a hunting club. The problem was that the club didn’t know what to do with it. They’d parked boats in the living room and used the kitchen as a slaughter room. At some point it was basically abandoned. Animals got in the house and birds nested inside.

When the Land Trust got it, they didn’t know what to do with it because they didn’t have the money to do this massive restoration. Joel was eventually contacted because of his excellent work on the L.A. house and he said he’d come out and have a look at it. He took me along with a couple of other people from Los Angeles and one of those persons was his business manager.

I’d always wanted to see Auldbrass. I’d never seen it, only the drawings and they were gorgeous – a very creative and inspirational piece of work.

When we got there it was just derelict. What a shame. The original copper roof was buried under layer upon layer of patched roofing. It looked like and old lumpy carpet. Windows were smashed. Animals were in the house.

MS: It was in pretty rough shape.

ELW: Extremely. But Joel looked at it and his business manager said, “Joel, don’t touch it. Don’t touch it with a ten foot pole.” And Joel looked at him and looked at the house and said, “I like it. I think it’s beautiful. It’s got real possibilities.” So he made the arrangements with the Land Trust and agreed to certain stipulations – if the property wasn’t properly restored it would revert back to them and that he had to open it to the public [on occasion]. Then we started work.

MS: The initial restoration took years and involved incredible attention to detail. This also included completing parts of your grandfather’s original plans that had never been realized for whatever reasons.

All of this is beautifully documented in David De Long’s Auldbrass: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Southern  Plantation. In the forward Silver writes that it’s ironic Auldbrass was conceived the same year Gone With The Wind was released, since it’s conceptually as far from Tara as one can get.

Plantation. In the forward Silver writes that it’s ironic Auldbrass was conceived the same year Gone With The Wind was released, since it’s conceptually as far from Tara as one can get.

ELW: That’s right. It’s exactly the opposite direction.

MS: Your grandfather once said, “Buildings, too, are children of Earth and Sun.” My first impression of Auldbrass was “organic” – a design philosophy your grandfather pioneered and you and your father continued.

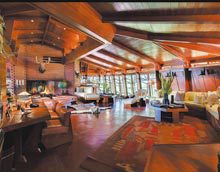

ELW: Oh yes. Absolutely. My grandfather pitched the walls at about 9 degrees. Structurally, that’s very sound because as loads go the building can’t cave in. But he said if you look at an oak tree it doesn’t stand vertical. There’s always a lean to it about 8 or 9 percent. So one of the things he did was to lean that house to be part of that oak swamp it’s in.

Also every 5 feet he built into the walls 2 by 12 trusses that went up from the ground in columns to support the roof joist. He detailed a pattern on them, and what he was doing was abstracting the trunks of trees, so you have all these trunks of trees. The house, by the way, is designed on a hexagonal unit, so the walls are all 120 degrees apart or 30 or 60 degrees apart and those are the angles within the house. There are no 90 degree walls at all.

MS: None within the entire structure, if memory serves.

ELW: Not a one. He also had double 2 by 6 roof joists going up like the limbs of a tree. The roof itself was copper that turned a verdant green once it oxidized, so that it’s like the leaves of a tree. Hanging off the end of the roof were these very detailed wood features built around the downspouts. They’re actually abstractions of the moss that hangs from the trees. When you look at the house it’s like an abstract oak forest.

MS: During the renovation you rediscovered a lot of your grandfather’s original concepts that were never carried out, including these hanging moss designs.

ELW: As Joel and I were going through the drawings, we came across this drawing of an absolutely gorgeous piece of copper work for the downspouts. It was much more beautiful than the wood. But we realized the wood had been put in as a cost expedient because the house was being built during World War II. Copper was hardly available and they had to use copper foil for the roof, which disintegrated after about ten years. So we decided to put those copper downspouts up and see what they look like. Of course, they were so gorgeous we didn’t take them down.

MS: This brings up another aspect of your grandfather’s work. The attention to every last miniscule detail is mind-boggling, and it’s inescapable at Auldbrass.

ELW: That was part of his getting into the abstraction of the form. In the nature of architecture, if you’re really following through natural patterns, they are complex. He was a master at bringing out this complexity. He was always critical of how well these details were done. That was a very important part of his work.

MS: What was he like to work with?

ELW: He was very good to work with, but he could get very angry if things didn’t go right. He did have a temper. He also had a certain stubbornness, which is natural. He was very sure of himself. The problem was that I don’t think he ever fully realized that the rest of us were having difficulty keeping up with him. He just assumed we knew what he wanted. We could never meet that expectation because he always expected us to know what he knew (laughs).

MS: Among all the detail w ork is the distinctive Auldbrass logo that he used to great effect.

ork is the distinctive Auldbrass logo that he used to great effect.

ELW: He used it all around the house. Some people say it represents Indians in a boat.

MS: I’ve heard that. I’ve heard all sorts of things.

ELW: (Laughs) I’ve heard all sorts of things, too. Unfortunately, I never heard what my grandfather thought, and I don’t know anybody who did. (Laughter)

MS: Well, so much for that. Because this is a private home and there is such limited public access, Auldbrass remains one of your grandfather’s lesser-known works. (Fallingwater is probably the best known.) Where do you think he would rate it in his body of work?

ELW: I think he would put it very high. One of the reasons being he was able to do a complete farm unit. He always loved the idea of a whole unit – a house, a farm and an office. He did that with his own home, Taliesin. That was a farm unit as well as a studio and a house.

I always think that Auldbrass has a unique place in my grandfather’s work. There are many similarities in his building, particularly the houses, but this is unique. It just hasn’t been repeated in any of the other work. Auldbrass is certainly one of the major works of my grandfather.

MS: Frank Lloyd Wright was way ahead of the curve on Organic Architecture and Green Building, something both y ou and your father continued to be passionate about. Architecturally speaking, where do you think we are headed as a nation?

ou and your father continued to be passionate about. Architecturally speaking, where do you think we are headed as a nation?

ELW: I think we’re sort of at a crossroads. I’m a little disappointed in what they call Green Architecture. A great deal of it is green because their energy budgets and so forth meet a certain criteria, but they’re all mechanically equipped. It’s not an integrated part of the design. It’s often separate from the design. To me, Green Architecture also has to be beautiful.

MS: On your website you refer to the “soul” of a structure. There’s precious little soul in this age of McMansions and generic gated communities, but just one glance at Auldbrass and the soul is staring back at you.

ELW: If you look at some of the homes he designed at the turn of the 20th century, they’re still remarkable more than a century later. Unfortunately most of the houses today are builders’ homes. There are very few architectural homes, and there’s been a retrogression in the builders’ homes. There’s nothing that is unique or organic. You’ll find it occasionally with architects but not the mass builders.

MS: Tell me about the Wright Organic Resource Center.

ELW: We’re a small non-profit organization and we’re involved in spreading the word about Organic Architecture, which by its very nature is green. We try and reach young people especially. We have workshops two or three times a year up in the Santa Monica Mountains. These workshops and classes are open to about 40 people and we always try to fill half of them with inner city students. Education is very essential. We want to spread the word on Organic Architecture and Green Building.

THE LECTURE

The Beaufort County Open Land Trust presents an evening with Eric Lloyd Wright Saturday November 5th at the USCB Performing Arts Center in Beaufort. Tickets are still available and proceeds go to support the vital efforts of the Trust. For more information call 843-521-2175 or email info@openlandtrust.com

For more information on Auldbrass go to www.openlandtrust.com

Photographs of Auldbrass courtesy of Anthony Peres