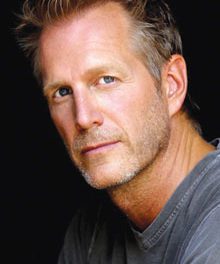

Oscar Winning Sound Editor/Designer Eugene Gearty to Receive Conroy Lifetime Achievement Award at BIFF

Oscar Winning Sound Editor/Designer Eugene Gearty to Receive Conroy Lifetime Achievement Award at BIFF

Story & Photos by Mark Shaffer, Editor at Large

There is a moment in Martin Scorsese’s period epic Gangs of New York where Daniel Day Lewis’ Bill “The Butcher” Cutting is confronted by Jim Broadbent’s Boss Tweed for his very public murder of the local sheriff. The lord of the Five Points may be a homicidal maniac, but he is a man of principle who long ago cut out his own eye to prove his self-worth. He’s slicing up a steak with a very sharp knife, seething in rage. The tension is palpable as Tweed declares, “You don’t know what you’ve done to yourself!” Bill glares up at him then slowly taps his glass eye with the point of his blade. Tink, tink, tink, tink, tink…

“That was pretty cool, right?” says Eugene Gearty. He’s the guy who put the tink, tinkin Bill’s eye. What comes after that moment, courtesy of the incomparable Day Lewis, is raised to a different level by Gearty’s simple sound effect. Both of them got Oscar nominations.

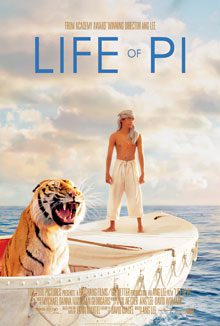

Gearty is a distinguished alum of Boston’s prestigious Berklee College of Music, class of ’82. But his focus on music gave way to a fascination with the emerging technology of digital recording. He took a degree in audio engineering with his sights set on landing a studio gig recording rock or jazz, but was soon drawn to brand new frontier. “I realized music is great,” he says, “but it’s one component of sound and that’s really when I fell in love with the idea of doing soundtracks for film that involved sound effects and everything.” Hebecame one of the first digital sound editor/designers in the film industry, pioneering sound effects for A-list films like Men in Black (he created the SFX for the Neurlyzer and the Noisy Cricket). He was also forging creative bonds with colleagues in his field and top directors like Oscar winners Spike Lee, Joel & Ethan Coen, Ang Lee and the master, Martin Scorsese. His work with these last two visionaries is both prolific, unique and decades long. He scored Academy Award nominations for Lee’s Life of Pi and Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, winning the Oscar for Best Achievement in Sound Editing for Scorsese’s Hugo.

Gearty is a distinguished alum of Boston’s prestigious Berklee College of Music, class of ’82. But his focus on music gave way to a fascination with the emerging technology of digital recording. He took a degree in audio engineering with his sights set on landing a studio gig recording rock or jazz, but was soon drawn to brand new frontier. “I realized music is great,” he says, “but it’s one component of sound and that’s really when I fell in love with the idea of doing soundtracks for film that involved sound effects and everything.” Hebecame one of the first digital sound editor/designers in the film industry, pioneering sound effects for A-list films like Men in Black (he created the SFX for the Neurlyzer and the Noisy Cricket). He was also forging creative bonds with colleagues in his field and top directors like Oscar winners Spike Lee, Joel & Ethan Coen, Ang Lee and the master, Martin Scorsese. His work with these last two visionaries is both prolific, unique and decades long. He scored Academy Award nominations for Lee’s Life of Pi and Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, winning the Oscar for Best Achievement in Sound Editing for Scorsese’s Hugo.

In a business built on ego, you’d naturally assume a guy at the top of his very specialized profession with a trophy case full of awards would, well, have a trophy case. No. The waterfront Sea Island home he shares with his wife Suzie is practically void of such stuff. In fact, the entire collection – including his BAFTA for Hugo and Emmy for Boardwalk Empire – occupies a dark corner of the studio over his garage filled with guitar cases and various electronic tools of his trade. A fly tying bench sits in a corner over a staircase festooned with fishing photos. No movie stars or Hollywood big wigs in sight. In fact, if you were to stumble onto the space you’d probably miss the impressive collection of gilded validation on first glance.

In a business built on ego, you’d naturally assume a guy at the top of his very specialized profession with a trophy case full of awards would, well, have a trophy case. No. The waterfront Sea Island home he shares with his wife Suzie is practically void of such stuff. In fact, the entire collection – including his BAFTA for Hugo and Emmy for Boardwalk Empire – occupies a dark corner of the studio over his garage filled with guitar cases and various electronic tools of his trade. A fly tying bench sits in a corner over a staircase festooned with fishing photos. No movie stars or Hollywood big wigs in sight. In fact, if you were to stumble onto the space you’d probably miss the impressive collection of gilded validation on first glance.

In early February we sat down at his kitchen table to talk about a groundbreaking career that spans nearly four decades with more than 100 credits. And counting.

Mark Shaffer: Was there a particular film that inspired you at some point?

Eugene Gearty: That requires some thought because it’s all retrospect now. (Long pause) I saw Apocalypse Nowwhen it came out and I walked away from that movie thinking that it was seamless. And then in learning about the film, becoming obsessed with the film, and it being the yardstick for all of us in the industry, it is sound dissolve after sound dissolve. There are only one or two super hard cuts like [the “Valkyrie” scene] when the helicopters are coming in and [Coppola] cuts to the village they’re about to attack. It’s dead silent. Almost every other shot in that movie is full of sound dissolves. And I was aware of that at 18, or whatever. Again being in the industry, that film, and [Sound Designer] Walter Murch’s work, became the blueprint for guys my age, mostly because the equipment was so hard to work with back then.

MS: You were at the forefront of the digital revolution when you started out editing, now you’ve got a team. How have things changed?

EG: The computer I was editing on was the first digital editing system of the time and I was “the kid,” fresh out of school. But everything else was still analogue except this thing I called the coolest pinball machine. You normally would start out as an editor or assistant editor cutting Foley, cutting sound effects and then work your way up to Sound Supervisor and then you hire your crew. That’s typical. I was never really keen on the supervisory part of it. I was happy cutting sound effects and designing sound. It became necessary for me to get the bigger credit to be recognized by the [Motion Picture] Academy. It was obvious to all of us that I wasn’t going to get a nomination as a sound effects editor for best sound effects editing unless I was a supervisor. So, Phil Stockton – with whom I won the Oscar for Hugo – we co-supervise many, many films.

But I’m really very old school in the sense that I like to cut all my own films. The last couple of films haven’t been quite that way, but going back to, say, Hugo or Life of Pi, I cut 95 or 100 percent of those films.

But I’m really very old school in the sense that I like to cut all my own films. The last couple of films haven’t been quite that way, but going back to, say, Hugo or Life of Pi, I cut 95 or 100 percent of those films.

MS: I saw an interview with you and Phil breaking down the flying fish sequence in Pi, which is breathtaking –

EG: It is!

MS: But all that sound had to be generated.

EG: Totally. Everything.

MS: How did you approach that?

EG: Initially I was looking for that fluttering sound that we could get Doppler type “pass bys” as they flutter past. But the visuals told the story: we wanted this oncoming onslaught of sound that’s confusing to both Pi and the tiger, Richard Parker. It was a dream to work on that scene and it got even better because there was a music cue written for it and Ang chose not to use it and go with all sound effects. We had a lot of music in that movie. It was a great score and won an Oscar, but I really worked on that scene as a standalone sound design piece and I thought the energy was really there with the sound effects.

MS: And it nabbed an Oscar nomination.

EG: Right.

MS: I want to talk about another nominated film that I think must have had a very complex sound design: Gangs of New York.

EG: Yeah. Absolutely.

MS: The challenge there was to create sounds for a time that’s long gone.

EG: Correct.

MS: And it’s a cacophony. The whole film’s sonic chaos for the most part.

EG: Yeah, totally: 1860’s New York. I did a lot of reading and what was really interesting was the amount of harbor activity that went on at that time. That got me recording vintage steam whistles. Met a guy in Jersey, he had like 15 of them but no rig to set them up. But he said, “ You should go to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. There’s a guy over there obsessed with steam. He’s got hundreds.” His name’s Conrad and he’s this old school engineer with muttonchops and the cap and he’d actually built a steam calliope.

MS: He’s living in the period.

EG: (Laughs) Oh yeah. When I walked into his place it was like a steam punk dream, all metal and brass. So, I recorded the calliope and about a dozen steam whistles in the quad at Pratt and that became a significant part of the soundscape. We used it to great effect in a very quiet scene without music when Amsterdam has slept with Jenny and he wakes up to Bill the Butcher sitting in a chair draped in an American flag.

EG: (Laughs) Oh yeah. When I walked into his place it was like a steam punk dream, all metal and brass. So, I recorded the calliope and about a dozen steam whistles in the quad at Pratt and that became a significant part of the soundscape. We used it to great effect in a very quiet scene without music when Amsterdam has slept with Jenny and he wakes up to Bill the Butcher sitting in a chair draped in an American flag.

MS: It’s an absolutely chilling scene.

EG: It is. And Bill’s got this monologue, “I don’t sleep much ‘cause I gotta sleep with one eye open and all I’ve got is one eye.” (Laughs) I presented Marty with a number of attempts to create this solemn background to this intense moment. We were very delicate with it, but the mournful horns came into effect there really well. For that I was nominated for mixing. Even though I’d done all the effects editing it wasn’t recognized as that. I was on the [mixing] board along with Tom Fleischman, who just got his lifetime achievement award from the Cinema Audio Society. He and I did get a CAS nomination for The Irishman, but no Academy nomination.

(During the course of the conversation Eugene predicted Ford vs Ferrariwould take this year’s Oscar for Sound Editing. It did.)

MS: And that brings us to your latest collaboration with Martin Scorsese and his legendary editor Thelma Schoonmaker. During a recent interview she talked about how The Irishman was the opposite of something like Gangs, that, “Marty wanted to feel the silences.” It is a quiet, intimate film and that makes the sudden violence that erupts all the more unnerving. What sort of planning went into this?

EG: Funny you should ask. A lot of planning went into it. We prepped that movie like every other movie – you hear a dog you see a dog, etc. All that was done ahead of time. When we got to the mix Thelma said that Marty wanted very much to draw the audience in, so any extraneous sound we were going to [de-emphasize] or toss out.

Bear in mind, two years prior I get a laundry list from Thelma of scenes they want fleshed out with sound effects. I was working on Mary Poppins Returns at the time. I got some time on weekends and I approached about ten scenes in the movie. It was quite involved. It dawned on me after I did all that that if they hadn’t asked for it yet, it’s not important to them. So, I actually didn’t do the sound editing on that movie other than the stuff in the film I did two years prior. They wanted nothing more than that. At the mix, by day three, I pulled my faders down to zero and would only bring in sound when it was needed for them. There was no way we could approach this movie like, “I’m a sound designer. I’m a mixer. I’m going to show you what I think this movie should sound like.”

MS: So in effect, you made it quieter?

EG: Correct. And they wanted that to such a degree that it was initially frustrating. But it was the right call. I think it shows great experience and artful creativity to approach it in that way. It fascinates me. I was learning the whole time.

MS: Is working with Scorsese like going to school?

EG: Definitely. That’s a good way to put it on so many levels. First of all he is really an engaging, nurturing director. I’ve heard dozens of actors who say Marty loves actors and he loves the idea of their performances. He coaxes that out of them in a humane or clever way, none of the usual bombast. He’s not that way with the actors and it comes to us that way. He’s always trying to help me [understand] him. What he wants from me might be quite simple but he wants my take on it to have some depth, not just a sound effect from the library. [Scorsese & Schoonmaker] break a lot of rules and you’ve got to love ‘em for that because it really does work.

EG: Definitely. That’s a good way to put it on so many levels. First of all he is really an engaging, nurturing director. I’ve heard dozens of actors who say Marty loves actors and he loves the idea of their performances. He coaxes that out of them in a humane or clever way, none of the usual bombast. He’s not that way with the actors and it comes to us that way. He’s always trying to help me [understand] him. What he wants from me might be quite simple but he wants my take on it to have some depth, not just a sound effect from the library. [Scorsese & Schoonmaker] break a lot of rules and you’ve got to love ‘em for that because it really does work.

MS: The Irishman is a Netflix film, and streaming is changing the cinematic landscape faster than anyone anticipated. How does that affect your work?

EG: I just met with the head of post production at Netflix. He was telling me that in the future we’re going to be doing our home theater version before the theatrical version because that’s where 98 percent of Netflix customers view the movie. I think the idea of the spectacle [aspect] of movie going is deteriorating, becoming smaller. So, those movies have to be bigger and more immersive, almost like rides.

MS: And finally, what was it like winning the Oscar?

EG: (Laughs) I’ve said it so many times; winning is SO underrated.

Join the author and the Oscar winner at the Beaufort International Film Festival for An Afternoon With Eugene Gearty, Friday February 21stat 4pm. Get more at www.beaufortfilmfestival.com