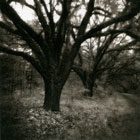

Beaufort filmmaker and photographer Gary Geboy is the featured artist in a ground-breaking one-man show currently on display at the Charleston Center for Photography through the end of the month.

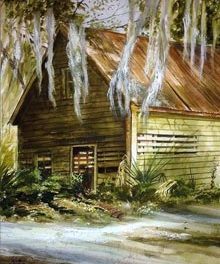

The exhibit is a striking combination of platinum/palladium prints – an expensive, labor intensive process – including work inspired by Geboy’s book Transfer of Grace: Images of the Lowcountry. The show also features the debut of an edgy new collection Geboy calls “The Lost,” representing “people and places lost to time.” In a word the work is best described as “haunting.” The Lowcountry’s Mark Shaffer recently sat down with the artist at his home to talk about his work and how “The Lost” was found.

Finding The Lost

Mark Shaffer: “Some of this show represents a culmination of 30 years of images collected from around the world.”

Gary Geboy: “About half of the photographs are photos I’ve been taking over the course of 30 years. I got really lucky [as cinematographer]. I got to travel all over the world all the time. So when I was working I carried a little point-and-shoot camera wherever I went. When I wasn’t working, I’d just walk the streets and photograph whatever interested me. It all sort of fell into this category of things that we call ‘lost’ – things lost to time, people who’ve been lost to the rest of civilization, who live on the streets – ”

M.S. “ But also places, as well.”

G.G. “ Places as well, cities. A pyramid in Peru that looks like a big dirt pile eroded by the rain but it’s actually a pyramid that is long lost. None of [the work] was cohesive enough to put together as a group. They were all pretty individual photos. Then last year I was looking through some and reprinting some and decided to turn it into a more cohesive idea and that’s where we came up with “The Lost.

[For instance] a photo I took 30 years ago of a guy sleeping on the street fit really well into that whole context. And for me it speaks of a bigger picture. We’re forgetting about a lot of people, a lot of places that don’t really fit in.”

M.S. “On a recent trip it became so apparent that everything’s beginning to look the same. Every intersection and interstate stop looks like the last one or the next one.”

G.G. “We’re losing part of what made us all different. In that sense we’re losing part of our humanity, that sense of individuality.”

The Shroud

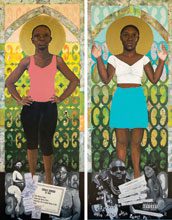

M.S. “How do you deal with your human subjects?”

G.G. “People that I photograph I always ask if I can photograph. And I always chat with them for a little while to find out what’s going on. That way if they want to change their mind they can and it gives them an opportunity [to choose] how they want to be photographed. I don’t like to sneak up on people. I don’t like to catch people off guard because everybody has their moments when you can be put in a very compromising position, and I certainly want to maintain that person’s dignity.

M.S. “Is that a common thread through this show as well, dignity?

G.G. “Yes and no. It’s a hard thing to say. There’s one shot of a guy who’s lying down in a back alley with a sack of what I suppose were all his possessions. So I’m walking through the alley and I ask him if I could take his picture and he said, ‘sure.’ I’m getting ready – I don’t just snap real quick, I give people time to do what they’re going to do – and he rolled over so all I could see was his back and his head lying on this thing. And when I [processed] the photograph, years later, I called it “The Shroud” because his shirt was so dirty that it almost had a life of it own. And just by seeing the back of him, and the form of his body and the grunginess of it, I think it’s a much more powerful photograph that way.

There was another time when I was in Memphis and I was just a hanging out and this guy walked by and I said ‘hi’ to him and he said ‘hi.’ He was an older guy on crutches. He went down [the street], turned around and came back and said ‘do you want to take my picture?’ And I said ‘sure, why not?’ He went past me and just walked right by me again – didn’t stop.”

M.S. “No posing.”

G.G. “No posing – and I took his picture and that one’s in show. I think that what he wanted me to see was that here was this guy who couldn’t move his legs, he could just sort of pick himself up and move himself along, but he wanted somebody to see that he was a human being, that he was there. That one had an effect on me, but they all sort of have an effect on me.

The Haunting

M.S. “The word ‘haunting’ is used to describe the show. That is the word I would use most to describe this work. There is a real chilling aspect to a lot of these photos.”

G.G. “That’s intentional in part because of the way I print them, but it’s intentional also because there has to be some sort of shock value because we’re so barraged with images every day. You see thousands and thousand of images. People get used to seeing all sorts of stuff, so you have to create a mood, you have to create something that people are going to remember after they see [it]. If that [happens] by making [the photos] sort of haunting and dark then perhaps they’ll remember what it’s all about, too. Maybe something will register in their heads. It’s not that I’m trying to save the world or anything like that, it’s just the little things that you want to keep making people aware of – that not everybody is as fortunate as everybody else.

Gary Geboy (www.garygeboyprints.com) lives in Beaufort with writer Teresa Bruce (www.teresabrucebooks.com), who wrote the narrative for Transfer Of Grace and who occasionally enjoys “interpreting” inanimate objects.

Find “The Lost” and much more at The Charleston Center for Photography, located at 654 King St. suite D, Charleston, SC. Phone 843.720.3105 for information or visit them on the web at www.CCforP.com.

Mark Shaffer can be emailed at backyardtourist@gmail.com