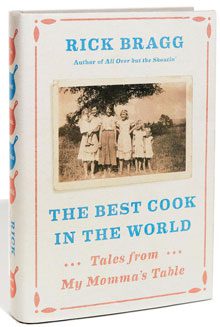

A conversation with award-winning, bestselling author Rick Bragg

A conversation with award-winning, bestselling author Rick Bragg

By Mark Shaffer

“In a south that no longer seems to remember its heart, our food may be the best part left. It is the opposite of the bloody past, the doomed ideals, and our still-divisive, modern day culture; it is a thing that binds us more than it shoves us apart, from each other and the rest of the world.”

-Rick Bragg, The Best Cook in the World

Margaret Bragg answers the phone with a simple “Hello” drenched in an Appalachian accent as thick and sweet as cane syrup.

“Is Mr. Bragg available?”

“Which one?”

“Rick, ma’am.”

“He’s downstairs,” she says. “You’re gonna have to hold on. You’re just gonna have to hold on, now.”

She delivers the last line with a slight sense of urgency. And while I’m certain that, like my own mother, this is rooted in a simple lack of faith in modern communications technology, it has all the weight of sage advice for living in this modern world. And if anyone has a recipe for living life, it’s the Best Cook in the World.

Rick Bragg shares his mother’s beguiling drawl and if you pay attention, you can hear that accent in your head when you read the words he writes about his momma:

“She spiked collard greens with cane sugar and hot pepper for old men who fought the Hun on the Hindenburg Line, and simmered chicken and dumplings for mill workers with cotton lint still stuck in their hair. She fried thin apple pies in white butter and cinnamon for pretty young women with bus tickets out of this one-horse town, and baked sweet-potato cobbler for the grimy pipe fitters and dusty bricklayers they left behind.”

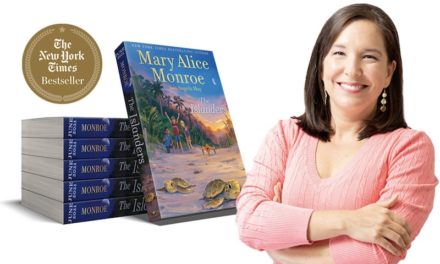

The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and bestselling author comes to Beaufort in early November to take part in the Pat Conroy Literary Festival. Bragg’s been compared to his old friend more than once, lofty praise for any writer. But I’m guessing if you said that to his face, he’d blush and change the subject. The slightly eerie fact remains that while speaking to him via a highly reliable relic of a bygone era called a “landline,” it occurs to me that the similarities to Pat didn’t end at the bottom of a page.

Mark Shaffer: How’d you get involved in the festival?

Rick Bragg: After Pat passed I did some memorials, around the country, around the south, of course. And I would see [Pat’s wife] Cassandra [King], and other folks. It’s funny. Pat was one of the most loving people in the world, but he always wasn’t the nicest talker to people who were close to him, you know, he’d let you have it this way in which you knew he was just pushing your buttons, and pulling your strings. And there were all these people, saying all these sweet and loving things about him, and I thought to myself, “I’ll bet somewhere he is sitting up there just laughing out loud.” And when the Conroy Institute (whether they call it that or not) – when it became a reality, you know, it was just nice to be asked.

I live about as far from the South Carolina Lowcountry as you can get, both horizontally and vertically. We’re here in the mountains of northeast Alabama, and that is where Cassandra has roots and ties. You know, like a lot of writers, Pat would reach out to me no matter where I lived, and he would give me one of those Pat Conroy messages that was part – mostly – pep talk, and partly castigation, you know, for something that you weren’t even sure if you did wrong.

MS: That was Pat’s sense of humor.

RB: Yeah, it was always, “It’s up to me to keep this dying friendship alive.” Later I learned he did that to so many other people. And this message would go on and on and on – and he’d always end it by saying, “I love you, son.” And how do you not, how do you not honor somebody like that? Despite himself, you know?

that to so many other people. And this message would go on and on and on – and he’d always end it by saying, “I love you, son.” And how do you not, how do you not honor somebody like that? Despite himself, you know?

MS: What was your relationship like with Pat?

RB: Oh, I would see him – sometimes it would be planned, like an event in Birmingham where he was not feeling real good and me and Cassandra would – well, anyway they asked me to do a little part of the program just in case. Now nobody steps in for Pat Conroy. Nobody. And it’d be like all those times somebody would co-host for Johnny Carson. And you’d have a long dinner and great talks, and you’d get the chance to sink the fishhook into him for a change. And, then there were accidental meetings in the hallway of a hotel, where we were both on the program but we both were going in and out real quick.

And, I never will forget, not long before Pat passed, I was at the Alabama book festival in Montgomery. Pat didn’t have to be there, but he went to sign books for his readers. And it had been one of those days where there were a couple hundred or more people lined up in the hot sun, and you’re sitting outside signing the books, and it’s Alabama in the springtime, and it’s just a good day. And there are so many people and you’re hopeful about books, and your book life and all that, and the line finally works down to about three or four. And I look over, and Pat Conroy has materialized in the chair next to me. And he looks at me and says, “Bragg, someday I hope your book career advances to where you have more than two or three people in your line.”

MS: (Laughter) That’s perfect.

RB: I’m usually pretty quick on my feet – but as usual with Pat Conroy – I just did a face plant. There’s nothing to say, because he had me.

MS: And he planned it …

RB: Yeah, he hooked me, and he reeled me in, and there was nothing I could do about it. And, I know that if he didn’t give a damn, if he hadn’t been such a champion of my books, and had not written the best book blurb ever written for anyone in the history of blurbs, for me. Then you know, I guess it would still be little things like that, that lets you know he cares about you.

I know one thing, I watched him eat like eighteen oysters one night at Highland Bar and Grill in Birmingham, Alabama, and it was the only time we didn’t really have a good talk, and it’s because he was knocking down oysters.

MS: That’s something I want to touch on, the mutual love of food. You mentioned in your Southern Living tribute, that Pat came to visit your mom and siblings, and Cassandra was with him, and he brought half of a German Chocolate cake?

(Laughter)

Did you ever figure that out?

RB: Yeah, I did! I finally got up the nerve to ask Cassandra, and apparently they both believe that if you go visit somebody, you take something. And they had been at a family reunion close by, because Cassandra has kinfolks around this part of the world. And the story was that there was half of a German Chocolate cake, so they just left with it to bring it to us. I think Pat probably ate half of it. But, it was really funny because if it had been a small cake, there’d been no debate. But my mother would look at me and she’d say, “You know, that’s the first time anybody ever brought me half a cake!”

MS: Yeah, it’s kind of a landmark.

RB: But it was such an odd thing, because as soon as Pat and Cassandra got there, she called everybody. So my aunts came, and my brother and sister-in-law came. I think even more dogs showed up in the yard than usual.

(Laughter)

MS: And of course, that would be perfect for Pat because he would have fed off of that audience.

RB: I know that he did, because he talked about them and said nice things about them. And he just seemed to love them. And of course my aunts, my elderly aunts, are story tellers. And my mom too. So yeah, he was at home, he was perfectly at home. And I think one of my friends drove all the way from Birmingham. It was very strange. It was probably any other celebrity or writer’s nightmare, to show up in Alabama and have all the fifth cousins and friends and aunts and the dogs – and have everyone show up. But Pat just seemed to glory in it, just seemed to relish it. It was a very, very, very good day.

MS: That brings us to the new book, The Best Cook In The World. Just a few pages in, I was in love with your mother. So I’m glad I got to talk to her for a moment. This is one of the most southern things I’ve ever read, and I remarked the other night, that it’s a cookbook in the way, “Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?” is a musical.

RB: (Laughs) Well, that’s – I’ll take that in a minute, sure.

MS: It’s a brilliant hybrid. You went on a mission with this book to preserve your mother’s knowledge and skills because there were no daughters to pass it down to.

RB: My mother always – I’m sure my mother has many regrets. People always love to say, “I have no regrets,” and I think that’s often bull. But I think my mother had regrets, and the most profound of them – she didn’t have any daughters. She wanted daughters, she prayed for daughters, and instead she got three sorry boys, you know? And if she had gotten a son who was interested in the cooking – as so many southern men are – that might not have exactly been a dream come true, but it would have been close. It would have been an acceptable alternative. But she didn’t get boys who were interested in cooking. She got boys that were wild. Even me – while I loved books – I still loved everything else about being a southern boy. I loved dogs and guns and fishing and running around on a motorcycle, and laying on some lake somewhere being especially sorry.

The cooking we took for granted. The good food, made from so little largess, we took for granted. The hard work, we took for granted. And she would have loved to have had someone to pass that skill to, as it was passed down to her. And we almost let it get away.

MS: Well, not anymore. You know, Sean Brock’s opening up Husks right and left. People are flocking to Birmingham and Charleston and New Orleans from all over the world. Southern cuisine is upscale and expensive now, and if you look at it – it’s mostly what Tony Bourdain would call “poor people food.”

RB: It is. I went to an upscale restaurant in Alabama, and they attached some name I didn’t recognize to the turnip greens. And tofu hoecakes. But then there is just the traditional southern food, that is – don’t get me wrong – it’s very, very good. But if you took your family of four out, you would spend the entire grocery bill, the light bill, water bill, and the cable, to eat it. And the fancier they try to make it, the more layers of pretention they try to weave into it, the worse it gets. And the further it gets from, you know – collard greens cooked with just the right amount of salt, the tiniest amount of sugar, and just the tiniest, tiniest amount of clear pepper sauce. Never heavy doses of anything. My momma’s chicken was dusted with flour – dusted with flour.

And I can see her with two drumsticks between her fingers – one between her little finger and ring finger, and the other between her index finger and her forefinger, and somehow using one hand to knock those pieces together and get the flour off. Not on, to get it off. And every crumb – every crumb – that wound up on the bottom of the plate, you didn’t let go. And man, she fried everything. She fried the gizzard and the livers, and the backbone. I remember chicken backs and lima beans, and thinking it was the best thing in the world anybody had ever had. And I ain’t likin’ lima beans. And I sure didn’t want the chicken back. I wanted chicken. I wanted a leg and a thigh. But nowadays I relish it, I really do.

I’ll sit and watch people do southern cooking on cooking shows. I used to love Justin Wilson – because my momma said he had such joy in his face, he seemed to enjoy his cooking so much, and he wove in stories. And with mom, it was the story. It was the story that led to the food. Because if there had not been the story, there would not have been the recipe in her mind. You know, biscuits and cornbread and things like that would have been driven into her mind over the years, but some things, it was the little memory. Like watching somebody knead the day-old white bread into the hamburger meatloaf, and you’d think, “Well, it’s going to be doughy.” It wasn’t. If you kneaded it in completely, it was like some kind of pudding. Like, just rich and redolent with green onion and white onion, and no twang of raw ketchup on the top. If there was any kind of sauce on top of it, it was cooked until it caramelized. The meatloaf itself would be something you could eat with a spoon.

MS: Did Pat ever have a chance to eat any of your mom’s cooking?

RB: I would have given anything in the world if he had, but no. And man, when they first met she was in her prime as a cook. She had all those hundreds of years – it seemed – of recipes in her head, and all those ghosts walking through her kitchen. And in my mind’s eye I think, Pat would have stood there and watched her.

MS: He was a student of cooking and I’d bet that one of his proudest achievements was his own cookbook.

RB: And it’s Pat Conroy writing a cookbook. What’s better than that? And the few times, the handful of times I got to eat with him, were the few times I saw him quiet. He seemed very much at ease, very much at peace. And I didn’t know how to take that Conroy – quiet!

(Laughter)

MS: The man cooked spaghetti for Barbara Streisand.

RB: I’m telling you. I think if Pat had ever cooked anything for me, he probably would have dosed in like a quart of pepper sauce on my plate before he gave it to me.

(Laughter)

MS: Years ago Josephine Humphries told me, “The south isn’t so much a place as it is a character.” Is that how you feel?

RB: Yeah, although that character shifts dramatically from region to region. There is definitely a commonality. And I think the food shows that. Look, you don’t see any people from the hill country where I’m from, go down and turn their nose up at shrimp and grits. They love that food. And I’m sure Pat would have loved my momma’s pinto beans and ham. I know that.

But, I think the landscape becomes a part of everything. Here, we’re in the throes of fall, and believe me, we have beautiful falls – but the thing that will be with me is we also get a little wind this time of year. Hearing that wind rush through those pine barons and the sound of that wind in the pines – you immediately begin to think of the south in a romantic way. You can’t help it. You think of the old song, “Whispering Pines,” and it occurs to you, that the wind may howl in other places, but here it hisses at you; it hisses. Halloween’s coming and it’s perfectly fitting. And you hear that – man, you hear that sound. It’s comforting now, but when I was a little kid I could just imagine those ghosts flitting in and out of the pines.

Whenever I think of the foothills of the Appalachians, I think of my Uncle Ed in his oil-stained khakis swinging a sledgehammer, and me holding the chisel, that Winston dangling out of his mouth. Whenever I think about the foothills of the Appalachians, I think of toughness, and women in hot kitchens, and women in sweatshops with that stabbing needle of that sewing machine going, but a hundred of them in a row. And maybe the Yankees look down upon us and think, “Well that’s the way it is here.”

I almost had a woman out in Seattle threaten to whip me because I said that southerners were the toughest people on the planet, and mountain southerners especially, and she said, “Listen, my people hauled in nets.” She remembered hauling in nets that had ice on the lines. And you know, maybe they all think we’re hogging that notion, know what I mean?

MS: I do know; I lived in Seattle for while.

RB: So you do know what I mean. But I do believe in my heart, that it’s storytellers like Pat, like Willie Morris, like McMurtry out in Texas, and Charles Frazier and Ron Rash in the Carolinas, and so many others I’m leaving out like Eudora Welty, like Cassandra writing about her people. I think the great storytelling does maybe a better job of weaving of the place and the people together, if that makes sense?

MS: It does, it makes perfect sense to me. So, where do you see Pat in the pantheon of southern literature? Where’s history going to shake him out?

RB: He came obviously a generation or so later than Thomas Wolfe, and Faulkner, of course, and so many of the others, but I don’t think Pat has to worry about what generation he lands in. We can say he’s one of the greatest writers of our generation and that is absolutely untrue. He’s one of the greatest writers of any generation in the Deep South. And it’s not because I knew him. It’s not because he laid hands on me, or because I was blessed by him somehow. Anybody that reads his work, or has ever heard him read it aloud, knows that there is an elegance and a power in that work that will stand through any generation. And, any generation of southern writers. And I think that he will – assuming that people will still care about books in the future, and I know they will – then Pat will have his place among the greatest southern writers of any time. I think anyone who believes otherwise obviously is not using all their thinking power.

Wasn’t that a kind way of putting it?

MS: That is a kind way of putting it.

RB: You could also maybe say, “Bleeping dumbass,” or however you wanted to.

(Laughter)

MS: That’s good too.

The 3rd Pat Conroy Literary Festival runs November 1-4. Rick Bragg discusses his new book and longtime friendship with Pat Conroy in conversation with historian, Walter Edgar, 3:30pm, November 3rd at the USCB Center for the Arts. Find the festival schedule and reserve tickets online at www.patconroyliteraryfestival.org