On the water with oyster farmer Frank Roberts

On the water with oyster farmer Frank Roberts

Story and Photos by Mark Shaffer

As I ate the oysters with their strong taste of the  sea and their faint metallic taste that the cold white wine washed away, leaving only the sea taste and the succulent texture, and as I drank their cold liquid from each shell and washed it down with the crisp taste of the wine, I lost the empty feeling and began to be happy and to make plans.

sea and their faint metallic taste that the cold white wine washed away, leaving only the sea taste and the succulent texture, and as I drank their cold liquid from each shell and washed it down with the crisp taste of the wine, I lost the empty feeling and began to be happy and to make plans.

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

ANOTHER DAY AT THE OFFICE

The late November sky is a flawless azure canvas reflected on the dead calm of the Coosaw River and set off by the slow seasonal browning of the spartina grass. The two skiffs are tied together floating over a field of large black mesh cages, each attached to a numbered buoy. The largest of these holds up to 600 pounds of Frank Roberts’ Single Lady  Oysters. A stainless steel sorting table on the bigger boat is loaded with a bounty of these. Most are destined for some of the finest restaurants in the Holy City. The tony diners at The Ordinary, Cypress, The Peninsula Grill and Fleet Landing can’t get enough. And when superstar chef and James Beard Award winner Sean Brock gets a whim to feature oysters at Husk, his Queen Street pantheon to fresh & local, he calls Frank. But nothing compares to cracking these briny little beauties open right out of the water while a dolphin cruises silently by in the distance.

Oysters. A stainless steel sorting table on the bigger boat is loaded with a bounty of these. Most are destined for some of the finest restaurants in the Holy City. The tony diners at The Ordinary, Cypress, The Peninsula Grill and Fleet Landing can’t get enough. And when superstar chef and James Beard Award winner Sean Brock gets a whim to feature oysters at Husk, his Queen Street pantheon to fresh & local, he calls Frank. But nothing compares to cracking these briny little beauties open right out of the water while a dolphin cruises silently by in the distance.

“Hey Frank. Got an oyster knife?”

There’s an awkward silence and then a brief search of both boats before the panic  subsides with the eventual discovery of a knife. John Marshall, chef and owner of Beaufort’s Old Bull tavern, takes the blade and pops open the shell with the expertise of someone who once worked a raw bar.

subsides with the eventual discovery of a knife. John Marshall, chef and owner of Beaufort’s Old Bull tavern, takes the blade and pops open the shell with the expertise of someone who once worked a raw bar.

“That would have been bad,” he chuckles. “Now, who brought the beer?”

Silence.

“Oh well.”

It’s been three years since we first featured Frank Roberts’ then fledgling Lady’s  Island Oyster Farm and much has changed. I’ve brought my friend John and my wife Susan for a first hand tour of what’s new. Susan’s in the lead boat with Frank and John. I’m taking notes and photos in the second boat piloted by Brian Cabral. According to Frank, Brian “just showed up one day last year.” Both he and his wife are passionate about mariculture and grew conch in the Turks and Caicos before landing in Beaufort. Brian spent part of his youth in the fishing village of Fall River, Massachusetts where he developed both his love of the water and his unmistakable accent. On the boat ride out he describes in detail his ideas for the future of the operation. “It’s gonna be wicked,” he says with a smile.

Island Oyster Farm and much has changed. I’ve brought my friend John and my wife Susan for a first hand tour of what’s new. Susan’s in the lead boat with Frank and John. I’m taking notes and photos in the second boat piloted by Brian Cabral. According to Frank, Brian “just showed up one day last year.” Both he and his wife are passionate about mariculture and grew conch in the Turks and Caicos before landing in Beaufort. Brian spent part of his youth in the fishing village of Fall River, Massachusetts where he developed both his love of the water and his unmistakable accent. On the boat ride out he describes in detail his ideas for the future of the operation. “It’s gonna be wicked,” he says with a smile.

When I first met Frank in late 2011 he was basically a one-man operation working out of his garage on Brown’s Island. “In the last three years it’s basically gone from me and a part time guy to three full time guys. And we’re looking to expand that.”

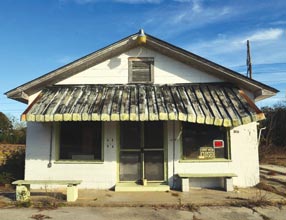

Last year everything changed. In gambler’s parlance he “went all in” and moved across the Whale Branch to an oak canopied acreage on McCauley Creek behind the old whitewashed Stokes Store on highway 21. He also partnered with local farmer, Irby West, who oversees the small farm operation that fronts the highway along with Frank Robert Sr. The move included a massive cleanup and restoration of the property as well as a new dock and construction of the hatchery. The next phase is an eventual restoration of the store into a market featuring Irby’s produce and Frank’s oysters, making it – as far as we know – the first such hybrid agriculture/aquaculture venture in Beaufort County and possibly South Carolina.

The new site also allowed for a significant expansion of the hatchery. It’s tripled in size to support Frank’s operation as well as others. Thre e years ago the hatchery produced half a million tiny seed oysters or spat almost entirely to suit Frank’s needs. He learned early on that in order to grow the business in the way he intended, he also had to control the source. This season the hatchery produced more than two and a half million spat. And not just for his beds but for a steadily increasing number of other local oystermen, as well.

e years ago the hatchery produced half a million tiny seed oysters or spat almost entirely to suit Frank’s needs. He learned early on that in order to grow the business in the way he intended, he also had to control the source. This season the hatchery produced more than two and a half million spat. And not just for his beds but for a steadily increasing number of other local oystermen, as well.

“I believe there are six growers in the area, now. Basically it’s a co-op,” he explains. “I set them up in a permitted area with the gear, if need be, and supply the oyster seed. They grow them, bring them back and I sell them.”

“Frank’s single-handedly making Lowcountry single oysters a brand,” says Marshall. John is an active supporter and advocate of local producers. When a group announced plans to convert an old chemical plant near Frank’s operation into a facility to process cannonball jellyfish, Marshall threw open the doors of the Old Bull to the opposition. In mid December Roberts was back at the Bull as the featured speaker for the monthly gathering of the local Greendrinks chapter. An overflow crowd packed the place to sample some oysters, hear about the farm and get an update on the jellyball fight. “Still hanging out there.”

“He has the true soul of a farmer and wants people to know how good we have it here,” says John Marshall. “He can talk all day about his product and people were excited to sample that product and hear him talk about the future of mariculture and Beaufort’s place in it. It was an awesome event.”

Oyster fact: the Chesapeake Bay once had boasted an oyster population capable of filtering the entire body of water in 3 days.

So what makes these particular mollusks so special?

“They’re unique to Beaufort County,” says Frank, “not just South Carolina, but Beaufort.”

The reason is simple. It’s the water. Frank’s lease runs through some of the richest tidal waters the east coast has to offer – the Coosaw, Morgan, Tombee and Bull Rivers as well as Parrot Creek and Half Moon Creek. All told, his lease covers an area of about sixteen square miles.

“There’s no contamination from freshwater rivers and streams collecting urban run-off from places like Columbia or wastewater treatment plants from another state.”

The ever-shifting tides make for an oyster Nirvana. “It’s typically ocean salinity,” says Frank . “And there’s no industry here, just marsh. Hundreds of square miles of spartina grass in the ACE Basin and we’re right on the western edge of it.”

. “And there’s no industry here, just marsh. Hundreds of square miles of spartina grass in the ACE Basin and we’re right on the western edge of it.”

Roberts’ system can produce a top quality market ready single in about 12-14 months. “In the wild that would take up to three years,” he says. “The conditions for growing oysters are real good.”

This is the understatement of the day. In fact, the conditions for growing oysters are nearly perfect. Few places on the planet can boast this any longer. Other more famous oysters from the storied waters of New England and the Gulf of Mexico simply taste bland in comparison.

Most weekends during the season you’ll find Frank shucking oysters at local farmers markets. Friday afternoons it’s Habersham. Saturday morning means Port Royal. Chef John Marshall has rarely missed a Saturday since he opened his restaurant.

“They’re absolutely phenomenal – comparable to any oyster in the world. They’re fat, they’re salty, they’re delicious. I wish my first oyster had been one of these local oysters.”

“Our oysters have that really nice brine,” says Frank. “It’s a sweet tasting oyster with a really clean finish. No lingering mineral or metallic aftertaste. I was shucking oysters at the farmers market and a lady told me I put just the right amount of salt on these.” He grins. “I told her you had to sneak up on ‘em to get the salt just right.”

Oyster fact: a single oyster can filter 40-50 gallons of water per day.

FROM SMALL THINGS

Roberts’ passion for oysters goes back to his boyhood and summer visits to the family farm on the shores of the Chesapeake, land originally granted by King George II. As a young Marine on Parris Island, Roberts looked out over the tidal rivers and salt marshes and saw unlimited potential. But when he first laid eyes on the Coosaw he couldn’t believe it.

“It was absolutely perfect. Still is. The best oyster habitat you can imagine.” And no  one was growing single oysters. Roberts saw a wide open market. All he had to do was figure out how to crack it, so to speak.

one was growing single oysters. Roberts saw a wide open market. All he had to do was figure out how to crack it, so to speak.

In the‘80’s he experimented with a homemade cage system built of pressure treated wood and galvanized metal. Within a few months woodworms bored through the lumber and the metal rusted. The cages may have failed, but while they held together the oysters flourished. Roberts knew the idea was sound; he just needed technology to catch up with him. And it did some years later with the introduction of a rust resistant coated wire mesh. After that it was a process of zeroing in on the optimum design for racks and cages, not to mention a lengthy licensing process and actually growing the oysters.

“It’s physically labor intensive,” observes Marshall, “and I’m sure it’s exhausting to constantly question and try to improve an operation the way Frank does. He’s out there every day recording and monitoring growth, constantly dealing with all these government agencies. But the result speaks for itself.” Just ask Frank.

“These are the best oysters you will ever taste. Period.”

To follow Frank Roberts’ example it seems to me that a modern oysterman needs to be in various degrees part engineer, biologist, inventor, mechanic, entrepreneur, environmentalist, and in Frank’s case something of an historian.

“I’ve got a chart from 1891 showing all the oysters reefs in my area,” he says. “And we’re slowly restoring every one of them.” One of the best ways to do this is by “green shelling” or simple shell recycling. Once the day’s harvest has been separated and processed at the docks the next boat out takes the leftover living, or “green” shell and dumps it in designated areas to build up native rakes. It’s a simple thing, but it’s indicative of the sense of stewardship Frank and his fellow oystermen embrace.

We’re back at the dock with a cooler full of the best oysters in the world, fresh from the Coosaw. All we need is a cold beer. But first a simple question.

“So Frank, with all this do you see the operation doing something more than just oysters?”

The reply is emphatic. The question still hangs in the breeze over McCauley Creek.

“No,” he says. “Do one thing and do it well.”

Read more about the Lady’s Island Oyster Farm here.rm here. Lady’s Island Oysters are available locally in season at The Foolish Frog and occasionally at the Old Bull Tavern and Wined It Up. Orders are available at singleladyoysters.com