The Backyard Tourist sits down with Charleston’s sibling foodie phenoms

Boiled Peanuts and Pickled Grapes

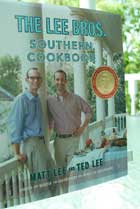

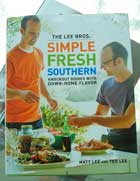

A few years ago Matt and Ted Lee gently shook up the culinary landscape with The Lee Bros. Southern Cookbook. Sprawled among its hefty five hundred and ninety pages were the usual suspects of the Southern table like Fried Chicken and Red Velvet Cake. But there were also exotic upstarts like Scuppernong Grape and Hot-Pepper-Roasted Duck. The book won just about every award out there and was honored as the 2007 James Beard Cookbook of the Year, the foodie equivalent of a Pulitzer. The brothers recently published their highly anticipated and less weighty follow up, The Lee Bros. Simple Fresh Southern. They also continue to run their successful mail order business and publish The Lee Bros. Boiled Peanut Catalog, the genesis of their second careers as writers.

As the new book hit the streets so did the Lees, only more so this time around.

Older brother Matt is traveling with his wife and infant son, Arthur, “the newest Lee brother.” At six months, Arthur’s already a seasoned road warrior, logging stops in Atlanta, Birmingham, Mobile, New Orleans, four in Mississippi, two in Tennessee and a blitzkrieg of North Carolina. This time around the minivan’s been replaced with a family station wagon. It’s the one loaded down with boxes of books and bags of Huggies. A hand truck and Arthur’s baby buggy are strapped to the roof. Beaufort’s one of the few stops on the current leg of the book tour where they’re not staying with friends or dependent upon the kindness of strangers. They’ve splurged and booked a pair of rooms in the City Loft Hotel for a book signing reception at Peggy Reynolds’ elegant Bay Street home. As always, the Lees are toting boiled peanuts. In fact, boiled peanuts are practically sacrosanct to the brothers.

Older brother Matt is traveling with his wife and infant son, Arthur, “the newest Lee brother.” At six months, Arthur’s already a seasoned road warrior, logging stops in Atlanta, Birmingham, Mobile, New Orleans, four in Mississippi, two in Tennessee and a blitzkrieg of North Carolina. This time around the minivan’s been replaced with a family station wagon. It’s the one loaded down with boxes of books and bags of Huggies. A hand truck and Arthur’s baby buggy are strapped to the roof. Beaufort’s one of the few stops on the current leg of the book tour where they’re not staying with friends or dependent upon the kindness of strangers. They’ve splurged and booked a pair of rooms in the City Loft Hotel for a book signing reception at Peggy Reynolds’ elegant Bay Street home. As always, the Lees are toting boiled peanuts. In fact, boiled peanuts are practically sacrosanct to the brothers.

“We especially like to bring the boiled peanuts to high class parties,” Ted confesses. “That’s fun.”

“It’s like bringing the Ballantine Beer,” says Matt. The idea being that anyplace with cheap beer and boiled peanuts can’t suffer from too much pretense. It’s tough to cop an attitude while sipping cold brew and munching boiled goobers.

I’m invited over to the hotel for a pre-signing sit-down and snack. Ted fishes something out of a Mason jar and hands me a plastic cup as Matt wanders into the room.

“I just gave him some pickled grapes,” Ted informs him.

“How’d they go down?” asks Matt.

I’m still a bit stunned. “They went down surprisingly well. In fact, they took me completely by surprise.”

And they did, although the concept takes a bit of getting used to. This is my first pickled grape experience and this rendition – from the Lee’s own kitchen – is a swirling contradiction of sweet, tart, sour and garlic that all somehow comes together. Matt and Ted Lee love pickles – all kinds of pickles. The new cookbook, Simple Fresh Southern, has eight pickle recipes. The first book had an entire chapter devoted to pickles and relishes – summer staples in the Southern kitchens of cooks with gardens and friends with gardens.

The pickles, peanuts and cookbooks all flow out of a time when the two brothers were stuffed in a tiny apartment on Manhattan’s lower east side, fresh out of college and homesick for their beloved Charleston.

Warning: this interview will make you hungry

Ted Lee: There’s three feet of snow outside, it’s February and you don’t know how you ended up in this place.

Mark Shaffer: And not a boiled peanut or a bowl of grits to be found.

Matt Lee: People assume in this era that foods are distributed everywhere, but there are certain foods that are here and not there and others that are there but not here.

TL: I remember it being particularly frustrating that boiled peanuts weren’t available because in New York City everything’s available. And that was why we thought we might make boiled peanuts the cool, hip bar snack. We had this idea they were going to go worldwide.

TL: I remember it being particularly frustrating that boiled peanuts weren’t available because in New York City everything’s available. And that was why we thought we might make boiled peanuts the cool, hip bar snack. We had this idea they were going to go worldwide.

MS: Didn’t quite fly in the Big Apple?

TL: No.

ML: No.

(Both laugh)

TL: The Southern restaurants in New York are all sort of Southern “themed.” If somebody’s been to Memphis that’s what barbecue is supposed to be. Boiled peanuts are just more regional. So nobody knew about them.

MT: So we figured the only way this was going to work was to sell them to people who already knew what they were, needed them and hankered for them – expatriate Southerners like us. Mail order seemed the most efficient way to do that. Our little boiled peanut project got written up in the New York Times, June 1st 1994: Boiled Peanuts Now Available by Mail-order. They weren’t really at that point, but they were the next morning.

(Laughter)

And so the phone rang off the hook all day, June 1st 1994, and those ex-patriot Southerners began to ask for other items – stone ground grits, Duke’s Mayonnaise. This category of Southern foods that don’t travel very far opened up to us and we very quickly decided that putting together a whole catalog was a better way to go rather than just focusing on boiled peanuts.

TL: We moved back to Charleston that summer and set up in the little warehouse we have now on Broad Street and that fall we printed up a little mail-order catalog we stitched together on a sewing machine and we were off and running.

ML: It wasn’t a big business – still isn’t – but it grew a little bit each year and it’s what attracted the attention of Food & Wine, Saveur and Travel & Leisure. A few years later the Editor of Travel & Leisure called and said, “I’m a customer of yours and I think you’d do a good story about South Carolina.” And so we got our first writing assignment and collaborated on it, which was perfect.

MS: How does that work, writing as a team? Who does what?

TL: We keep separate notebooks.

ML: There’s no duplication of research. We do everything together. With the writing, whoever’s in a better position to start off usually begins. That might be the one not working on another project or the one who’s least depressed at that moment.

(Laughter)

TL: The first person goes as far as they can until they get blocked and then we hand it off. It’s like having an in-house editor with writing privileges.

ML: And then you also have to split the meager proceeds, which makes it less worth doing except that we see a bigger picture in the way it all works out.

MS: Which brings us to the cookbooks. The travel writing was the genesis for the first book.

ML: Because we got into writing for the New York Times and were developing recipes to accompany the stories. Even for our story on northern Florida for Food & Wine we were developing recipes that were inspired by the travel. We realized that we had the chops to do recipe development. Even though we didn’t think of ourselves as cookbook writers, we realized we had enough recipes in us to get the ball rolling.

MS: How long did it take to put the first book together?

ML: It took us six years to put all the recipes together. The initial conception was to put one hundred recipes together and that took a year.

MS: How many did you end up with?

MS: How many did you end up with?

TL: Two hundred and twenty five, I think.

ML: We turned it in the summer following and we all realized it wasn’t going to be that kind of cookbook. It was going to be bigger, more epic – something that would hopefully translate to people all around the country.

MS: This involves a tremendous amount of research. The type of book you’re talking about is much more than a collection of recipes; it’s a cultural biography.

ML: And the more stories the better.

TL: The way I think of it, the first book is the cultural biography of the first thirty years of our lives. It represented all the experiences we had growing up in Charleston – learning how to crab and shrimp and that sort of thing – to first getting in the kitchen as teenagers. The second book picks up after that –

ML: – In the present tense.

TL: Now, we both have wives. Our families are bigger and we’re busier, so that’s where the whole “simple” thing comes in. Also the first book comes up to that point where we were both single and just starting to write about food and get excited about it. And there is nothing we love more than the challenge of something like a traditional gumbo with eighteen ingredients – the epic food day –

ML: – A food marathon.

TL: – Where you spend a whole Sunday just making that food. It’s so awesome.

MS: And before you know it, it’s a party.

TL: Everyone comes over and it’s a blast. This is more spontaneous, like the way we entertain in Charleston: it’s six o’clock, what are we going to do tonight?

ML: And you call around to your friends and see what’s going on. Maybe nothing’s going on. Well, I’m hungry. Let’s cook dinner.

MS: Southern spontaneity.

TL: Exactly.

ML: You can be that way to a degree in Charleston that you never could in New York. In New York everything is premeditated.

MS: We’ve touched on this before, you’re both married now and that changes the way you do everything.

ML: Extra hands in the kitchen, though.

MS: Sure, but now with a baby I’m guessing that whole epic thing happens a little less often.

MS: Sure, but now with a baby I’m guessing that whole epic thing happens a little less often.

TL: The amount of time we spend cooking together is more structured.

MS: How much time do you spend in the kitchen each week when you’re working on a book?

ML: When we’re not working on a book it’s about five nights out of seven, so that’s already a lot.

TL: We just don’t go out to eat.

ML: We can’t afford to eat out on a regular basis and maintain a budget – not to the degree that a restaurant critic would. So, we do cook a lot. The salvation of a food writer is that you can cook to put food on the table and pursue some question you’ve been asking at the same time, advance your knowledge of food as you feed your family. When we were developing Simple Fresh Southern we did what we’d done with the first book. We set aside two months that winter to try and get the lion’s share of the recipes hashed out – four recipes a day, four days a week. We hired an assistant to do the shopping so we didn’t have to put the rest of our lives on hold. We went about our business until around five o’clock when the ingredients would show up and then we’d just dive into the prep work. We have our laptops in the kitchen so everything goes right into the computer. The flour’s flying around and everyone’s tasting things and riffing ideas off of one another.

TL: Most nights that goes on till around eleven.

ML: And then you’ve got a refrigerator full of leftovers. It’s a neat process and it’s intense, but after a couple weeks of that we’ve got sixteen tight recipes–

TL: –That we’re ready to send to the outside tester.

MS: The publisher’s having them tested again?

ML: The publisher makes you pay for the photos and the testing.

MS: That’s got to be expensive.

TL: You could go broke writing a cookbook.

ML: And most people don’t have the recipes re-tested.

TL: But we feel that it was such a key part of our first book, and bringing a strict home economist perspective to a recipe is essential. The tester we use is in Vermont and she has no background in Southern food. We want these recipes to be cooked anywhere by anyone so we need to have those checks and balances particularly when it comes to substituting ingredients.

MS: What is a Southern cook and does a Southern cook have to be from the South?

TL: Well, that’s the question particularly as it concerns the Lee Brothers because we were born in New York City and raised in Charleston. Matt and I obviously think you can cook Southern even if you weren’t born to it.

ML: We think that Southern food is food that is either cooked in the South or is cooked outside of the South with an eye toward what’s happened in the South. For us the essentials to Southern food are Southern ingredients.

TL: That’s where it starts – the Southern palate.

ML: Even if you’re just rifling through an old Southern cookbook and it inspires you to get in the kitchen and do something, odds are that something is going to be good Southern cooking even if it’s a riff or an interpretation.

MS: What are the misconceptions about Southern food and cooking that just make you crazy?

ML: When someone says, “I just don’t cook like that.”

TL: This happened at a wine tasting in New York: the woman sitting next to me said that she loved the stories we wrote for the Times, that they had a lot of flair. And I said, “That’s great because we’re coming out with a cookbook.” And she asked what the cookbook was about and I told her it was all about where we grew up and the South. She said, “Oh, I don’t cook like that.”

MS: Ah, there’s nothing like the instant dismissal of an entire culture.

TL: And there’s the misconception that all Southern cooking is bad for you. And then there are the people who say, “Oh, we love it – all the fried chicken and barbecue.”

ML: And it’s so much bigger than that.

TL: And here’s one we get on the smart radio shows: “So guys, help us out here. Define ‘Southern food.’ And we’re like, “Where in the South Are you?” Asheville has a completely different cuisine than Charleston. Defining Southern food is like–

ML: –It’s like asking Mario Batali to define ‘Italian food.’

TL: Right! He probably has a great answer like “Italian food is the food of love.” But we’re obsessed with the details so we’re not going to say something like that. We can’t go straight to the platitude.

ML: We try and educate these people that the South is a huge place, tremendously diverse, with many, many cultural regions.

MS: A lot of West African influence in this area and of course there are vast differences in crops and animals and seafood, it’s not all like the Cracker Barrel.

TL: We were at the South Carolina Book Festival recently and there was a chef there from Mt. Pleasant, Charlotte Jenkins of Gullah Cuisine. She has an amazing new book coming out. A lot of it has to do with how she and her husband grew up. Her husband grew up thirty-five minutes south of Charleston on Wadmalaw Island. She grew up thirty-five minutes north of Charleston in Awendaw. Just within that distance their stories are so different. Her husband recalls drying shrimp on the roof to make this real funky, concentrated condiment.

MS: That sounds Asian.

TL: You also find it in West African cuisine. I asked their daughter, Keisha, about it and she said, “Oh, that stuff is nasty! That’s not how they cook in Awendaw.” Charlotte cooks like they cook in Awendaw. They’re only separated by forty or fifty miles, but in many ways are completely different.

ML: Awendaw is about crabs and flounder while Wadmalaw is more about shrimp and oysters and ocean fish. Charlotte also says that Awendaw is at “ten mile” – mile post ten – and there’s a town called Six Mile and one called Four Mile and they’re all different. Back before automobiles you’d be walking between these settlements and four miles is a long walk.

ML: Awendaw is about crabs and flounder while Wadmalaw is more about shrimp and oysters and ocean fish. Charlotte also says that Awendaw is at “ten mile” – mile post ten – and there’s a town called Six Mile and one called Four Mile and they’re all different. Back before automobiles you’d be walking between these settlements and four miles is a long walk.

MS: You ate what was available, local and fresh, an idea that’s finally beginning to come back around in South Carolina. Do you think the sustainable food movement can survive here?

ML: I hope so. California is where all of this might have started back in the late ‘70’s and even that was an imitation of a European mode of living where you go to the butcher and the baker. The message has spread slowly over the decades and it’s finally reaching South Carolina. You may lose something in terms of expediency and may have to pay a little extra, but the dividend s are flavor, freshness, health, quality and supporting your neighbors. In the last five years I think that message has reached a lot more people and at the same time we’re aware of the realities. Industrialized food is so much cheaper and available.

MS: And pervasive.

ML: And it’s hard to ignore. We eat at Macdonald’s when we’re driving I-95 and want a quick kangaroo burger.

(Laughter)

TL: When there is no other option.

ML: We also have our list of great little independent places to stop along 95.

TL: I have a sense that the mountain South is where the farmer’s market might be more sustainable. I’m not sure why.

ML: I can tell you why: because on the coast no one can afford to farm because the value of the land for resort and residential development is much too great.

MS: This is a massive problem on the Sea Islands and all along the coast.

ML: We see so much fallow farmland on the drive between Charleston and Beaufort and I just think, what a waste. But the price of fuel and the cost of doing business don’t add up for most farmers.

TL: Even in Naples, Florida where I used to spend Christmas cooking a lot of shrimp for my wife’s Grandmother, the stores don’t stock local shrimp.

MS: Welcome to Beaufort. We’ve got some of the best shrimp in the world coming off of local boats right out of these waters and most of the big chain groceries are selling imported, farmed shrimp right next door.

TL: It’s all cheap and flooding in from Thailand and Cambodia. You can’t tell me people won’t pay a couple dollars more per pound for something local?

MS: The crime here is that on average people are paying way more for the imported junk– and that’s what it is. It certainly doesn’t taste like shrimp.

TL: That really is a crime. I mean, you taste that imported shrimp and it’s mealy–

ML: – Tastes like dirt.

TL: – it tastes like a fish tank, like chlorine and algae and dirt. Fresh shrimp off the boat is sweeter than lobster. It’s crazy. We buy from a guy in Shem Creek just outside of Charleston. He has our cell phone numbers so he can call us and we can meet him at the dock. And we’ll take the assorted other stuff from the catch – the crabs, an octopus, whatever’s available.

ML: Get a nice relationship with a local fisherman. You can’t beat it.

TL: We were shooting the photos for the new book on Sullivan’s Island and I called up the Captain and met him at the dock because I wanted these guy to shoot the catch coming in. And these guys from New York had never tasted shrimp like this before in their lives. It was amazing. They’d only ever eaten farmed and shipped shrimp.

MS: What’s your favorite recipe in the new book for the perfect Saturday afternoon Southern soiree?

TL: For the main dish I’d pick the Pork Tenderloin with Figs and Madeira. Figs and Madeira are so Charleston.

ML: They’re associated with Charleston. Charleston didn’t invent them.

TL: Right, although Charlestonians like to take credit for a lot of stuff like that. There are fig trees all over Charleston. Everybody’s got a fig tree. Madeira is historically important to Charleston, and it’s something I serve at dinner when I’m trying to impress someone.

(Laughter)

ML: I might pick the Skillet-Roasted Quail with Tart Greens. That to me seems incontrovertibly Southern. And for starters: Collard Greens and Winter Root Soup. That’s a classic. It’s turnip greens and turnip roots diced small together. Adding the roots back into the greens adds a lot of flavor, makes it healthier. For a side dish with the pork I think the Pimento-Cheese Potato Gratin. For dessert, Teddy, what would you say?

TL: In summer, Drop Biscuit Peach Cobbler. It’s simple and cooks up in a skillet.

MS: What’s the one thing you always take with you on the road.

ML & TL: Boiled peanuts.

MS: We have come full circle. Pass the pickled grapes.

Visit the Lee Brothers online at http://mattleeandtedlee.com and check out the Lee Brothers Boiled Peanuts Catalog at – where else? – www.boiledpeanut.com

Mark Shaffer’s email address is backyardtourist@gmail.com