Part Eight: Tony Bartelme and the Pulitzer

You and I may be very concerned about the issues surrounding our homeowners insurance. But have you ever asked yourself the question, “Is it just us . . . or is this really a serious, widespread problem?” The Charleston Post and Courier can help us with the answer.

You and I may be very concerned about the issues surrounding our homeowners insurance. But have you ever asked yourself the question, “Is it just us . . . or is this really a serious, widespread problem?” The Charleston Post and Courier can help us with the answer.

Throughout all of 2012 their most- read series was “Storm of Money,” the series that connected the dots behind our homeowners insurance crisis. In January, “Storm of Money” was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for the “explanatory reporting” category. The Pulitzer Prize organization typically makes their announcement of the winner and two finalists on April 15. To be named as one of these three finalists is a gigantic honor for any newspaper and their investigative reporter.

On Thursday, April 11, I received a rather odd e-mail from J.P. Browning, the Post and Courier’s publisher. The message read: “Daryl, can you meet me in my newsroom next Monday at 3pm?” I thought for a minute. Why does she want to see me on April 15? What’s the purpose of this get-together? Then I thought, “When does the Pulitzer Prize organization make its announcement? That could be it. They make their announcement on April 15.” Glenna and I arrived a few minutes before 3 pm. The newsroom was crowded with employees waiting for the Pulitzer organization to announce their winner. Then, it came. The winner of the Pulitzer Prize for 2012 for Explanatory Reporting went to the staff of the New York Times. (The Times had published a story on how technology companies were adversely affecting many workers and consumers.) But who were the two finalists? Then the news came over the big screen in the Post and Courier’s newsroom. “The first finalist is Tony Bartelme of the Charleston Post and Courier for his captivating series, ‘Storm-of-Money,’ which detailed the mysterious world of property insurance and how and why homeowners are forced to pay such high insurance rates in South Carolina.”

The room erupted with applause. Tony Barteleme, and the Post and Courier had received some of the highest professional recognition possible. (The second finalist was Dan Egan of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel for his exhaustive examination of the struggle to keep Asian carp, and other invasive species, from reaching the Great Lakes.)

When I brought my research to the Post and Courier in March of 2012, the newspaper industry was hurting. The economy and the Internet were tearing into their bottom line. It was a rare newspaper that would commit to the kind of expense an investigation into SC homeowners insurance would require. For example, to check my research, the Post and Courier had to hire an independent simulation company to confirm my conclusion that South Carolina has a “relatively low risk” for hurricanes between Charleston and Savannah. But they committed to these and other expenses at the very time when it was most difficult to make the budget. That took courage and leadership.

That courage and leadership – not to mention Bartelme’s great work – triggered a series of events that will keep the public’s attention on improving the regulation of homeowners insurance in South Carolina. The Senate Banking and Insurance Committee intends to enter legislation during the 2014 session that will more tightly monitor the regulation of our insurance. A group of Beaufort County businessmen created a non-profit consumer group, The South Carolina Competitive Alliance, to push for regulatory change and to promote our coast during the fall of the year. We now know that our coast has the best fall weather, and least the hurricane risk, in the South.

To honor Tony Bartelme, the author of ‘Storm of Money,’ I asked the Post and Courier for permission to re-print one of the most captivating articles from his series. It’s fairly long, so Lowcountry Weekly will run it in two parts. If you like it, you might want to e-mail Tony. Congratulate him for being a Pulitzer Finalist and thank him for his invaluable work. You can reach him at: tbartelme@postandcourier.com.

From “Storm of Money” by Tony Bartleme, Charleston Post and Courier, December 2, 2012

Mark Romano gripped the steering wheel and tried to keep his car from swerving into another commuter on the busy Illinois tollway.

“God, please don’t let me hurt someone,” he prayed.

Dizzy again. These bouts of vertigo were barely noticeable at first, but something else was going on now. At night, he would lie in his bed, stare at the ceiling and watch everything twirl. In the morning, the spells came in waves during his commute to Allstate’s national headquarters in suburban Chicago.

Stress?

It was December 2007, and Romano was a senior manager at Allstate and its top expert in Colossus, a program that calculates how much a person might be paid for an injury claim. He was in charge of two projects to “tune” and “recalibrate” Colossus, work he knew could affect payments to thousands of people.

Colossus was part of a quiet revolution in the insurance industry.

Before the early 1990s, insurance was a decidedly human endeavor, especially when it came to setting rates and paying claims. To set premiums, insurers relied on computations from their actuaries — mathematical wizards armed with statistics and tables that assess various risks. When it came to paying claims, insurers often sent adjusters into the field, where they met face-to-face with people injured in car wrecks.

Today, insurers have an array of computer programs that guide the flow of trillions of dollars to and from customers around the world. These programs include sophisticated “catastrophe models” that use weather data and other factors to predict an insurance company’s losses in a disaster. “Scoring models” use credit histories and secret algorithms to estimate which customers are more likely to file claims. Colossus and similar programs help companies manage claims. Like a TurboTax program for medical injuries, adjusters plug in information about a person’s loss — from a damaged spine to a fractured finger. Colossus then cranks out a range of payments to cover the costs. Insurance industry critics and even many insiders call these programs “black boxes” because their formulas, data sets and operational policies are cloaked in secrecy.

Few people at Allstate knew more about Colossus than Romano. On organizational charts, he was Allstate’s Colossus “subject matter expert.” And in late 2007, at age 49, he was at the peak of his career, working in one of the nation’s largest insurance companies — and wondering whether he should leave it all behind.

Romano has thick black hair and wears thin glasses. His brown eyes widen when he wants to make a point. He had gone into the business to help people, but he knew that his work on Colossus would do the opposite.

During his hour-long commute to Allstate’s sprawling campus in Northbrook, his mind drifted to his daughter at the College of Charleston, to his son in private school, his wife’s multiple sclerosis, medical bills, his mortgage, the decades he put into his career. The dizzy spells grew worse. Doctors prescribed motion sickness medicine, relaxants and physical therapy. Then the headaches came — migraines as long and powerful as a Midwestern freight train, box cars of pain, one after another after another. Something had to give.

Birth of Colossus

Among computer programmers, the name Colossus has a rich history. In World War II, British code-breakers called their hulking new programmable machine Colossus and used it to decipher German teleprinter messages. In 1970, filmmakers released “Colossus: The Forbin Project,” a science fiction movie about an army supercomputer that tries to take over the world. (At one point, the computer tells its human creator, “You will come to regard me not only with respect and awe but with love.”)

The insurance industry’s version of Colossus was born in Australia. In the 1980s, a government-chartered insurer ran into financial trouble because of claim costs, which were growing at an annual rate of 14 percent. The insurer set its sights on its adjusters.

It’s the adjuster’s job to evaluate people’s losses and come up with ways to settle their claims. This often meant assessing what people did in their careers and how an injury might affect their future income and overall enjoyment of life. Longtime adjusters talk about the challenge of sizing up people when they’re suffering, and the knowledge adjusters need, from medicine to car repairs, to calculate a fair settlement.

The inherent complexity in putting numbers on injuries also meant that adjusters often came up with different amounts for similar types of claims. In Australia, payments varied by more than 80 percent. So to reduce these disparities and lower overall costs, the Australian insurer worked with a software company on a novel idea: embed the experience and knowledge of their best adjusters in a computer program.

The programmers studied how top adjusters made decisions and then created software to mimic their work. This program became known as Colossus and required answers to as many as 700 questions, ranging from the severity of injuries to how people experienced the loss of enjoyment in life. Injuries were broken down into 600 different codes. The program analyzed legal settlements and jury verdicts, combined this information with data entered by the adjusters, and generated what were supposed to be fair settlements.

A few people questioned whether computer programs were up to this complex task. An Australian law professor wrote that the development of Colossus was “just one instance of an important challenge of the information age: how to ensure that computer-based decision making is fair and non-discriminatory.” But Colossus was a huge success. Within a few years, payments for similar claims were more consistent and the costs of those claims had stopped rising.

In the United States, the insurance industry was experiencing its own period of self-analysis. It began in 1989, when Hurricane Hugo flattened parts of South Carolina. The storm caused $4.2 billion in damage to insured property — at the time the most expensive loss in history. The second wake-up call came in 1992 when Hurricane Andrew generated $15.5 billion in claim payments, $10 billion more than actuaries had predicted. Andrew bankrupted 11 insurance companies and prompted dozens of others to flee the Florida market altogether.

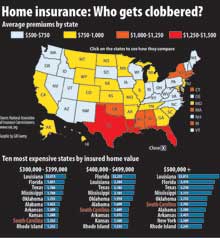

Amid this sticker shock, industry leaders asked why they had so badly underestimated their potential losses. They found answers in newly created “catastrophe models,” computer programs that predicted potential damages in a hurricane or other disaster. These models warned that future hurricanes would be even more costly, and with these new predictions in hand, insurers soon justified massive rate increases in home insurance premiums, especially in South Carolina and other coastal states.

While insurance premiums are the insurance industry’s main source of income, payments for claims are its biggest costs, the equivalent of rubber for a tire manufacturer. Claims also are at the heart of why people buy insurance. Insurance is based on the idea of sharing risk, a grand communal exercise that involves collecting $4.6 trillion every year from people across the world and then shifting some of this to a smaller pool who suffered losses. Insurance keeps communities destroyed by disasters on life support until their economies recover; it helps keep people out of bankruptcy after car wrecks and house fires. And it was largely for these noble purposes that Mark Romano decided to make insurance his life’s work.

An adjuster’s story

Romano grew up in Tampa, Fla., and by his account had a relatively uneventful childhood. He loved catching and dissecting animals for biology classes and thought someday he might go into medicine. He played trombone in the high school band. His mother was a school librarian. His father was regional director for the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, and Romano remembers his dad coming home angry about how consumers had been bilked in one way or another. After high school, Romano enrolled in Florida State University, where he gravitated toward the school of insurance and risk management. “I was interested in the basic concept of risk, that you could transfer it from one person to an entity or spread it among many people,” he said. “And you were helping people, and I grew up with two parents who in one way or another helped people.”

Romano’s first job was as an adjuster with American States Insurance, and his first day at work came after a drenching Florida rainstorm. His boss told him to grab a map and clipboard and take measurements of damaged homes. “It was overwhelming, but it was cool,” he said. “I absolutely loved being on the road. Everything was face to face, and it would be very common to meet people in their homes, sit in their kitchen and talk about their injuries.”

Romano handled auto insurance claims and worker’s compensation cases, learned about medicine, the law and how to establish rapport with people in distress. “You did it all, and it was an incredible education in how the world works.” Not all of this education was positive. A year into his career, he took over a new territory, and when he introduced himself to auto repair shop owners, “One guy said, ‘Hey, do you want the same deal as the other guy?’ ” Romano wasn’t sure what to do. “I went to my father and said, ‘These people are offering me things.’ And he said, ‘Don’t you dare ever do anything like that.’ That’s how naive I was at that point.”

But the vast majority of those he met were “really good, decent people trying to put their lives together.” He remembered a case in which he helped a family set up a scholarship to honor their child, who had died in a car wreck. By then, Romano had moved to another company, Hanover Insurance, which had a charismatic chief executive officer named Bill O’Brien. “For him, it was all about empowering employees at the lowest level possible. And we were never told to watch or shave anything off a claim payment.” If a customer’s claim was too low, it was the adjuster’s duty to pay them more. “You really felt good about what you were doing.”

Then, after Hurricane Andrew in 1992, Hanover Insurance started closing offices in Florida. It also was a pivot point for Romano. He was mid-way into his career and eager to advance. The place to do this was Chicago, a mecca of property and casualty insurance. He would take a circuitous route to get there, though. He left Hanover and took a job at CNA insurance division in upstate New York, where he learned about a program called Colossus.

By then, the Australian creators of Colossus had sold the program to Computer Sciences Corp., now named CSC, which licensed it to Allstate and many other insurance companies.

CSC’s marketing materials have long touted Colossus as a way to help insurers “establish consistent recommended settlement ranges,” Edward Charlton, a CSC vice president, said in a statement to The Post and Courier. “Without a clearly defined process or framework in place provided by a software tool such as Colossus, claim adjusters may skip important steps or forget to ask pertinent questions of consumers,” he said.

In Romano’s mind, it made good business sense for companies to automate claim payments, though he feared something could be lost without a more personal touch. And based on his years working as an adjuster, the payouts Colossus spit out for CNA seemed fair. He excelled in his job and eventually was transferred to CNA’s bright red headquarters on Chicago’s Wabash Avenue. As he walked into the building, he looked at the skyline. All around were skyscrapers adorned with the names Prudential, Blue Cross, Kemper and Hancock, huddled like giants overlooking Lake Michigan’s southern arc.

To be continued in the next issue of Lowcountry Weekly…

(To read the whole article online, visit http://www.postandcourier.com and go to “Storm of Money.”)

To read more from The Billion Dollar Coastline Series, go to Local Color.