Part Two: Enter a “Deep Throat”

Read Part One: The Discovery

It took three years of digging. I had solved the dinner party question. Hurricanes usually turn away from our coast during the fall season. And now I know why. Yes, it is possible for them to break through; but it is rare. What lay ahead of me was nothing short of a Sherlock Holmes story. But in this case, it was a true story… one that I will never forget. And this story involved a “Deep Throat.”

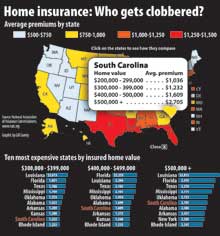

The minute I reviewed the findings, I asked myself, “If it is true that hurricanes tend to avoid southern South Carolina during the fall, why are my homeowner insurance rates so high?” I live on a bluff overlooking the Whale Branch River. Engineers tell me that the area has the highest elevation in the county. My foundation is 23 feet above mean tide. I don’t carry any flood insurance. However, I considered my homeowner’s insurance very high. So, I asked myself, why is it so high? I called my insurance company and laid out a test. My idea was this: I would compare my homeowner’s bill to that of a house of the exact value . . . located in the heart of the Katrina Hurricane in Mississippi. Specifically, that would be Gulf Port, Mississippi.

I knew from the National Hurricane Center that Gulf Port, Miss. has a hurricane risk that’s at least 2.5 times greater than Beaufort County’s. Thus, I told myself, I would expect their rates to be proportionally higher.

I made my call. I told the service rep. that I was considering moving from my existing location. I informed her that I either wanted to rebuild a $400,000 home on my existing lot or purchase a house of the same value in Gulf Port, Miss. The house would be several miles from the Gulf. The representative got back to me quickly. She informed me that her insurance company does not cover wind insurance in Mississippi . . . but that homeowners insurance would be $488. The cost for insuring the same house on my lot in Beaufort County – without wind and flood insurance – would be $1,400.

This shocked me! Even if the insurance company excluded future “wind” costs, why would insurance rates in Beaufort County be three times that of Mississippi? – http://1st-casino-game.com/microgaming/

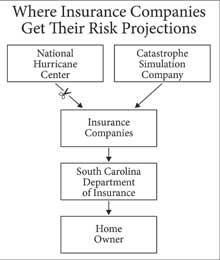

I wanted to immediately call the South Carolina Department of Insurance and see if they had the answer. But I reminded myself that I’d better check and see how an insurance company now gets its assessment of coastal risk. I am glad that I paused. I quickly discovered that insurance companies no longer use hurricane risk projections from the National Hurricane Center. In the early 2000’s the industry got clobbered with losses from a series of hurricane strikes along the Gulf coast. They ran out of reserves. They then turned to Catastrophe Simulation Modeling Companies.

These companies basically introduce large quantities of additional computer data along with scientific forecasts of future years. They make the claim that instead of getting a forecast based on 100 years of data, they can offer the equivalent of 100,000 years of experience. You and I see the results of their work in the incredible accuracy that we now see in the projection of hurricane tracks. There are about eleven catastrophe simulation companies. However, most of the insurance companies deal with only the largest three: Applied Insurance Research, EQECAT, and Risk Management Solutions.

Here’s the problem. These companies work for the insurance companies. They are paid by the insurance companies. So, outside of a few state regulators, you and I have no way to challenge them. No insurance company will allow you and me access to their actuaries, and they will never give you access to their “hidden” catastrophe simulation company.

But I had to talk to a senior officer of one of these simulation companies. I had to know if their risk assessment of Beaufort County matched that of the National Hurricane Center. After reviewing the background of the senior officers of the three largest catastrophe simulation companies, I called one of them . . . at his home. I introduced myself. I gave him a brief sketch of my background. Then, I simply said, “I have no dog in this hunt, I simply don’t understand how an insurance company, using your data, can give homeowners insurance rates that seem to be far from “relatively low risk.”

I was surprised. He was willing to talk. After the first conversation, I asked if I could call him back if I had more questions. He said, “yes.” After four more calls, it was obvious to me that he had a very personal reason why he was being so open with me. It became clear in the fourth call I made to him. I got much more direct. “Dr. X, I said, you still have not answered my question. You have the computer output. What is your company’s risk assessment of our coastline for fall hurricanes?” Then, he opened up. “It’s exactly what the National Hurricane Center told you. It is ‘relatively low risk.'” I asked him why it was low risk. He gave the exact reasons that the NHC had given. But then he really opened up. I asked, “How does your computer output differ from the NHC?” He replied, “We know your hurricane risk in much more detail.” I asked, “To what detail do you know the fall hurricane risk in Beaufort County?” There was a long pause. Then he said, “You did not hear this from me or my company, but your insurance company knows your risk by the house . . . by the lot.” I almost shouted. “Are you saying that my insurance company knows my fall hurricane risk compared to my neighbor’s?” He said, “Yes.”

I continued, “Then, why does my insurance company set just one or two rates along the South Carolina coast?” He did not answer. I asked him another question. “Dr. X, do you have the computer risk assessment for Beaufort County in front of you?” He said he did. So I continued: “What one factor does it show that is out of line? What one factor is abnormally high and, if addressed, could noticeably lower our homeowner insurance rates.” He answered. “You are not aligning your insurance rates to your building codes. In other words, you are not designing or building homes, or modifying homes, in ways that will give you the least future storm damage. The insurance company is not giving you optional rates based on designing the house better to withstand coastal wind. The architects are not giving you plans that will show different insurance costs. And the builders are probably not informed as to what they can do to help you. Furthermore, the state of South Carolina has tax incentives that will give you savings if you follow wind resistant plans; but they are not informing you.”

I had to ask one more question. “If we attacked this ‘building code alignment’ problem, how much could we expect to reduce our insurance costs?” He replied, “Southern Florida had this same problem. They instituted strong codes and aligned them from the insurance company to the customer. They reduced their costs, depending on the particular county, by 30-50%.”

There was absolutely no doubt what this senior insurance industry officer was telling me. He was sharing this information for only one reason. He felt some personal guilt that his industry was overcharging some states when the risk data did not support it. That is the only reason this man could possibly have shared so much confidential information with me. But with that knowledge, this Sherlock Holmes story got even more interesting.

I immediately placed a call to the CEO, the chief executive officer, of my insurance company. His assistant informed me that he was out of town. After I described why I wanted to talk with him, she informed me that she would try to set up a conference call with me and the company’s senior officer for actuary risk. Within an hour, she had set up that appointment. On the other end of the call was the company’s senior actuary and one of his officers. From their records they knew that I had been the president of the nation’s largest multi-utility. In other words, I had had the same job as their boss. This had to tell them that I knew the regulatory and actuary business pretty well . . . and that fluff answers would not be acceptable. And that is exactly what happened.

I started the conversation by suggesting that if we were to have a meaningful discussion about insurance rates, we both had to agree on the risk level assumptions of the South Carolina coast. They agreed. Then I proceeded to give them my assessment of the meteorological reasons why our coast had a “relatively low ” fall hurricane risk. They replied, “We agree with your assessment.” Then, I asked them the tough questions. “How can you explain my high annual premiums at these low risk levels?” I got no answer. But, they said that they would look into it. I then asked them, “Do you have the ability to set homeowner insurance rates by the house? After a long pause, I interrupted the silence by saying, “I have talked to a senior research officer of a Catastrophe Modeling Company.” They then said, “Yes, we can.” The meeting turned more productive once they made that statement. I asked them why they only had two rates along the entire coast, when they could set up to one million. They did not have a clear answer; but they noted that it might make a lot more sense to offer more rate areas. Two months ago, they called me back and told me that they were about to file for 517 rate areas along our coast instead of just two.

I had now had three confirmations that the risk along the southern South Carolina coast was relatively low during the fall. Within a few months the largest newspaper in South Carolina, The Post and Courier, would check my work and agree with me on our coastal risk. But I still had two questions to solve. Why are insurance rates so high if our risk is so low? And why don’t we see more tourists in Beaufort County if we have the best fall weather in the South?

In the next Lowcountry Weekly

Conversations with the people within the South Carolina Department of Insurance bring shock. Is it possible that this department is NOT regulating homeowner insurance? An expert checks my work and informs me of a secret law . . . a law that gives insurance companies automatic rate increases. And one insurance company asks for a 91% increase and gets it. Our state leaders are not interested . . . but the PRESS is.

Daryl Ferguson has lived in Beaufort Country since 2000. He is the past President of Citizen’s Utilities, America’s largest multi utility, and former Chairman of the Board of Hungarian Telephone and Cable, its second largest communications company. Daryl holds a PH.D in Business and two patents.