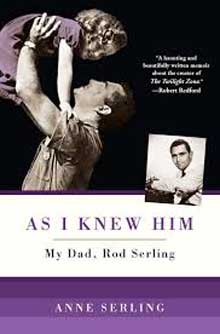

Local author Teresa Bruce interviews Anne Serling about her famous father Rod, her new memoir, and her upcoming visit to Beaufort for the Short Story America Festival.

I’ve been devouring memoir ever since I began to write one of my own, four years ago, about my relationship with Byrne Miller: The Other Mother. So when the folks at Short Story America and Lowcountry Weekly asked if I’d be interested in interviewing a memoirist who will be giving a talk at SSA’s festival in Beaufort, I jumped at the chance. And that was before I found out the author was Rod Serling’s daughter Anne.

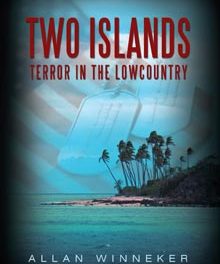

I picked the perfect time to read As I Knew Him: My Dad, Rod Sterling – curling up with it at the lake house in Wisconsin that belongs to the blissfully normal family I married into and thinking about what it would be like to grow up the daughter of a celebrity. I confess, most celebrity memoir holds little interest for me, but Rod Serling is different. And so is his daughter’s memoir.

Which is why I’m almost surprised it got published. In today’s insta-tweeting celebrity gossip world of publishing, it’s easy to find books about scandals, dysfunction and mommy-dearest confessions. When my agent first circulated a memoir I wrote about family, the rejection letters from publishers in New York often begged for more dirt, conflict, or wounds to re-open. And I wasn’t even writing about anyone famous. But Anne had an entirely normal relationship with her famous father and didn’t write the book until 38 years after he died.

Which is why I’m almost surprised it got published. In today’s insta-tweeting celebrity gossip world of publishing, it’s easy to find books about scandals, dysfunction and mommy-dearest confessions. When my agent first circulated a memoir I wrote about family, the rejection letters from publishers in New York often begged for more dirt, conflict, or wounds to re-open. And I wasn’t even writing about anyone famous. But Anne had an entirely normal relationship with her famous father and didn’t write the book until 38 years after he died.

Reading it is like meeting Anne at a birthday party and finding out what Rod Serling was really like. I was so relieved that perhaps the best television writer of all time was nothing like the bad-boys of TV writer’s rooms today. The man who invented The Twilight Zone would have had every right to be conceited. But I believe Ann Serling’s account that he wasn’t, because clearly he passed down the modesty gene.

“Although I am still young during several pivotal historic events, I readily adopt many of his ideals although I will never be as vocal, articulate, or eloquent,” she writes.

And yet Anne Serling can be all three, particularly when she shares her overwhelming grief at losing her father when he was only 50 and she was only 20.

“The doctor clears his throat again. ‘We are so sorry. He’s gone.’ Gone? Gone where? That’s the thing about euphemisms. They never speak the truth. They leave all sorts of questions and dangling expectations. ‘Gone’ would imply that he’ll return, or that he’s just momentarily slipped away.”

Her grief wasn’t tidy. Or brief. And in writing about it Ann Serling comes closest to her father’s skill. “I am prescribed Valium. Here’s what it does: Takes the edge off. Here’s what it doesn’t do: Bring my father back.”

Lucky for Serling fans who will hear his daughter speak at Short Story America, Anne found something that worked better than blame, fame or drugs: time.

Teresa Bruce: So many people have written so much about your father –”As I Knew Him” includes dozens of letters besides those you wrote to each other. Was it difficult to separate out your first-person memories of him, from the “collective” memory that builds up in retrospect?

Anne Serling: Not difficult at all. My personal memories of my dad are just that—my own, separate, and not in any way compounded or influenced by my dad’s public persona. The letters I included from his parents and from him to his parents only reinforced the dad I knew, providing glimpses into the boy that, in a sense, I already knew- – the child within my father.

TB: In your father’s letter to his unborn children on page 54 he writes: “But you, my children, I don’t want you to be among those who chose to forget.” He’s talking about the atrocities of war, but is there a link in that sentiment to why you wrote a memoir of your relationship?

AS: No. I began this memoir long before finding that letter. But it does speak to who my dad was as an eighteen-year-old suddenly thrust into war. I think it gives a pretty clear picture of how tuned in and passionate he was even at such a young age.

TB: I had the luxury of writing about my relationship with someone well known, but far from famous. Byrne Miller was a dancer, not a writer like your father. Did you ever worry that your memoir would be compared to Patterns or other pieces he wrote about his own life?

AS: Actually, yes. I think there is always a propensity to compare and that did concern me, but my goal was to write an honest account of who my dad was and then let the chips fall where they may. Thankfully, the reaction has been positive.

TB: You weren’t afraid to speculate on what he might have thought of certain events he never lived to see. So here’s one more. In Patterns, he wrote that the motion picture industry looked down at its newborn cousin somewhat as the president of a gourmet club might examine an aborigine gnawing a slab of meat. What do you think he would have made of the esteem in which television writers (particularly cable) are now held?

AS: Television certainly has come into its own, especially with cable television. Patterns was written when TV was a very young media and at a time when movie studios were afraid of losing money to it. My dad would see and understand that today’s cable channels have the money, resources and the freedom to be braver than the other channels and are able to bring better and different types of entertainment to the small screen. That said, I think he would have applauded the quality of shows such as (Aaron Sorkin’s “Newsroom”) and been horrified by the preponderance of reality television (“Honey Boo-Boo”) .

TB: How did your father’s stand against racism get communicated to you, his child? Did he ever talk directly about right and wrong beliefs or did you just understand the difference by osmosis?

AS: My father felt that prejudice was “the greatest evil of our time” and that was certainly clear from conversations in our home. Ironically his first glimpse of prejudice came from his own (Jewish) people when he was blackballed in high school from a Jewish fraternity for dating non-Jewish girls. And later, my grandfather (my mother’s father) “forbid” my mother to marry my dad because he was Jewish. This level of intolerance was clearly not acceptable. Also, shows like “Hogan’s Heroes” were banned from our house. As my father said, Now through the good offices of Hogan’s Heroes, we meet the new post-war version of the wartime Nazi: a thick, bumbling fathead whose crime, singularly, is stupidity—nothing more. He’s kind of a lovable, affable, benign Herman Goering. Now this may appeal to some students of comedy who refuse to let history get in the way of their laughter. But what it does to history is to distort, and what it does to a recollection of horror that is an ugly matter of record is absolutely inexcusable. Satire is one thing, because it bleeds, and it comments as it evokes laughter. But a rank diminishment of what was once an era of appalling human suffering, I don’t believe is proper material for comedy.”

TB: On page 165 you wrote about your father’s stand against censorship and it got me thinking. Your reflections of him are so uniformly positive and heartwarming. Did you ever worry about unconsciously censoring yourself as a writer?

AS: No, I said it the way it was. I didn’t have very many of the typical adolescent battles with my father and so there was never a moment where I weighed what I said about our relationship. I did however initially censor myself about my grief until my editor said after an early draft, “Your grief is so central to this book; you need to be more open.” After she said that, I opened up and just let it flow.

TB: Was it odd, or comforting, to find clues to your father’s true nature in the transcripts of television episodes?

AS: It wasn’t odd at all. If anything, several of the episodes, particularly the many that deal with social or moral issues were like an extension of my dad. Finding the episode “In Praise Of Pip,” the one where he used the routine he and I did, “Who’s your best friend/buddy,” was a poignant moment as I didn’t watch it until after he died and I had no idea he had done that. It was tremendously comforting – even revisiting it in The Twilight Zone!

TB: Your book begins and ends with poignant descriptions of the process of grieving. Obviously there are no universal truths, but what message of hope did you want to pass along by including this in your memoir?

AS: As I said, opening up to the level that I did about my grief was initially tough. When I did a reading before the book was complete, a woman came up to me afterward and told me her father had a terminal illness and that he would be gone any day. She said that after hearing me read, she knew that she would be okay. I was so moved by what she’s said and that my words had in some way helped her. It was an unexpected gift. All I could do was hug her. I was always embarrassed by my prolonged grief. After writing the book and hearing from people, I realized grief is not tidy and there is no preordained amount of appropriate time . . . it’s messy and can take years to resolve. That’s not ideal, but it’s okay. That’s the message.

TB: Finally, what draws you, an educator and a non-fiction writer, to a festival honoring the literary form of short story?

AS: I am in the process of writing a novel. As as it unfolds, I realize it is in essence an amalgamation of short stories and how that can be a powerful form of communicating ideas and feelings. That said, I am finding it to be an arduous process and so it is an honor to be included in the company of all of these great writers.

The Short Story America Festival and Conference will be in Beaufort September 26 – 29. To learn more and see a full schedule of events, go here.