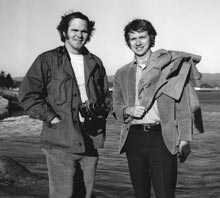

Bestselling author and Beaufortonian Pat Conroy remembers the friendship of a lifetime.

Bestselling author and Beaufortonian Pat Conroy remembers the friendship of a lifetime.

I was living with my family in Italy when I read a report in the International Herald Tribune about a mysterious disease that was killing gay men in San Francisco and New York. I ran to the telephone and dialed Tim Belk’s number in San Francisco. When he answered in his refined, cultured Southern accent, I said, “Tim, whatever you are doing in your unspeakable gay life, I want you stop this minute. No more hanky-panky for you, son.”

“So you’ve heard rumors of the plague as far away as Rome,” Tim answered. “Don’t you worry. You’re talking to Sister Timothy Immaculata at this very moment. I’m in the midst of a life of purity, chastity, and good works. I attract wolf whistles from the cutest boys wherever I go to the Castro district wearing my nun’s habit. But I keep tripping over these damn rosary beads.”

“No jokes, Tim,” I said. “This scares the living hell out of me.”

“It scares you?” Tim said. “I’m so scared by this, I’m thinking of going back to the dark side. I’m thinking about dating women again.”

“I’m not suggesting anything that drastic or repulsive to your deviant nature,” I said.

“Pat, you know I’ve always thought you were gay,” Tim teased.

“You told me I wasn’t good looking enough to be gay,” I said.

Tim said, “Sadly, you’re right. I think your dilemma’s incurable.”

As we were speaking that day Tim had already contracted the virus and the whole nature of our friendship was about to change. Because of the AIDS epidemic, I know of few American families who were not affected either indirectly or profoundly by the spread of the virus. It tore through the San Francisco area like some biblical plague that rolled across the city with that unearthly fog that stole up the Bay each afternoon. Only two of Tim Belk’s large circle of gay friends did not die from the disease. It cast a hangman’s pall over the entire city and caused unbearable grief in the households that had raised those boys across the American landscape. Over and over again I encountered friends of Tim whose families had renounced them forever when they found out their sons or daughters were homosexuals. These announcements not only infuriated these parents, but repulsed them to such a degree their sons and daughters arrived in San Francisco abandoned, without any bonds of family to support them. As a result, the gay men I met succeeded in forming themselves into an articulate tribe that was both rowdy and indivisible. San Francisco had freed them to be what they were born to be; AIDS made them political and the whole nation changed in its wake.

Tim Belk’s flat on Union Street turned into a visitor’s center for all of Tim’s South Carolina friends. A generous host, he entertained a traveling circus of his Beaufort friends and over a hundred of us stayed in his light-filled guest room on an alley that dipped down into the heart of North Beach. He gave a tour of the city that lasted for hours as he drove his car from Potrero Heights through Haight Ashbury, to the mansions of Pacific Heights, the carnival-like atmosphere of the Castro, to the alleyways of Nob Hill. People would stay a week at a time and sometimes longer. With the city laid out like a white chessboard below him and the blue gleaming Bay in the distance with its regattas, and ship traffic at the Marin Headlands in the distance, he would declare in a prayer-like voice that San Francisco was the most beautiful city in the world. Then, in a tribute to all of our shared past, he would admit that Beaufort was just as lovely in its own lush, indefinable way. Each year he returned to Beaufort and brought great joy with his visits, parties galore, and his singular gift for finding magic in every piano that came his way.

After he was diagnosed as HIV positive, Tim and I used to talk at least once a week.  As always, we talked literature, politics and music and he would tell me about the famous clubs and restaurants he had played in, from the top of the Mark Hopkins to Ernie’s and notable gay bars the length and breadth of the city. He also became famous for playing at parties for high society in San Francisco and over the years brought his skills into the peerless mansions of the Gettys and the Aliotos and would always draw a crowd with his compendious knowledge of song and the virtuosity he brought to requests for Chopin, Schubert, and Mozart. All this was done as Tim sat there in his tuxedo with his bourbon and lit cigarette and he kept up a charming line of social patter that had the entire room singing with him at the end of the evening. He made the whole American South look good in every room he entered and his southernness and handsomeness were all part of the package.

As always, we talked literature, politics and music and he would tell me about the famous clubs and restaurants he had played in, from the top of the Mark Hopkins to Ernie’s and notable gay bars the length and breadth of the city. He also became famous for playing at parties for high society in San Francisco and over the years brought his skills into the peerless mansions of the Gettys and the Aliotos and would always draw a crowd with his compendious knowledge of song and the virtuosity he brought to requests for Chopin, Schubert, and Mozart. All this was done as Tim sat there in his tuxedo with his bourbon and lit cigarette and he kept up a charming line of social patter that had the entire room singing with him at the end of the evening. He made the whole American South look good in every room he entered and his southernness and handsomeness were all part of the package.

In 1988, Tim visited me in Atlanta and I saw for the first time the price that AIDS had begun to exert on his body. He came to my house having lost over twenty pounds since I’d last seen him and with his face covered with sores I’d once seen on several of his friends.

“My God, Tim,” I gasped. “What’s wrong?”

“Come hug the Elephant Man,” he said and I did.

“Don’t worry, they can cure this. But soon, I’ll come down with something they can’t cure,” he said. “I think all this happened because I made out with some trashy girl in high school.”

“You wish,” I said.

The next year, my wife Lenore and I bought a house on Presidio Drive in San Francisco. Tim had not seemed afraid of dying, but very afraid of how he would die. His family was small and he feared being crippled or demented or incontinent. I heard it as a fear of dying alone. So my family and I moved to San Francisco and I moved there with the purpose of helping Tim Belk die. In the four years I lived in his city, Tim and I became best friends as the relentlessness of his disease began to exert its undermining power over him.

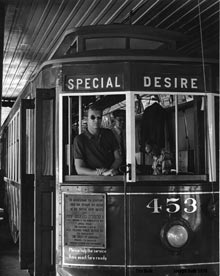

Each day we spoke by telephone and several times a week I would visit him on Union Street. On Sundays, we always had lunch at the Washington Square Bar and Grill and we sat at a place of honor by the window so we could observe the human traffic spilling into the park with its kites and Frisbee catching dogs. A community developed around us and Leslie was our sharp-tongued waitress and Michael poured our Bloody Marys and a whole civilization came and went as we sat and talked about the state of the world as fifty Sundays went by and Tim lost more weight. The movie version of The Prince of Tides came out in 1991 and I escorted Tim to every party I could and he was paid good money to play at several of them. He enjoyed the hoopla of the event far more than I did, but I’d fallen in love with movies when Tim Belk hosted a movie series at The Breeze theater back in Beaufort. At the premiere, Tim sat beside me and murmured with pleasure at the sumptuous music that opened the movie and the stunning shots of the town where we had first met twenty-five years before.

Soon after that premiere, one of Tim’s friends dropped by when we were having lunch and said, “There’s a gay kid from South Carolina who’s dying of AIDS. His family won’t have anything to do with him and his friends don’t know where he is. They’re frantic to find him.”

“Hey Tim,” I said, after his friend left, “I’ll be damned if I’m gonna let some kid from South Carolina die of AIDS alone.”

“I’ve been thinking the same thing,” Tim answered. “Let’s find him.”

So Tim Belk and I began to search a part of San Francisco we knew nothing about. I described this in South of Broad, when a gay man named Trevor Poe disappears from sight in San Francisco and straight friends go looking for him to bring him back to Charleston. Trevor Poe, of course, was the fictional counterpart of Tim Belk. Tim and I delivered lunch and dinner to dying men who were staying at last-stand hotels in the Tenderloin, a god-awful place on few tourist maps. We would bring meals to men who would be dead within the week or month. We made phone calls to their families, gave them money, bought them groceries. I always asked them if they had met any young man from South Carolina. After weeks of searching, we found the man in a hospital less than four blocks from my house. His name was Jay Truluck and he was from the town of Turbeville, South Carolina.

described this in South of Broad, when a gay man named Trevor Poe disappears from sight in San Francisco and straight friends go looking for him to bring him back to Charleston. Trevor Poe, of course, was the fictional counterpart of Tim Belk. Tim and I delivered lunch and dinner to dying men who were staying at last-stand hotels in the Tenderloin, a god-awful place on few tourist maps. We would bring meals to men who would be dead within the week or month. We made phone calls to their families, gave them money, bought them groceries. I always asked them if they had met any young man from South Carolina. After weeks of searching, we found the man in a hospital less than four blocks from my house. His name was Jay Truluck and he was from the town of Turbeville, South Carolina.

Tim and I found him in a garden, sitting in a wheel chair, completely blind. He was twenty years old.

“It could be worse, Jay,” I said. “You could be in Turbeville, South Carolina.”

Jay Truluck almost fell out of his wheelchair laughing.

“I’m from Fort Mill,” Tim said. “It couldn’t be that small.”

“Trust me,” Jay said. “It is.”

So we became good friends with Jay Truluck and his suite mate, Jimmy Love, and Jimmy’s exquisite mother and the golden-limbed Charlie Gallie who was taking great care of both young men and dozens of other stricken patients around the city. Charlie became one of our best friends from that day onward. Those years were terrible, but a strange aura of charity and goodness came together during that time of epidemic. All of us were having dinner at my house on Presidio when Mrs. Love received a phone call that both Jimmy and Jay had died just minutes apart. Tim and I met Jay Truluck’s mother and sister at the airport and drove them to the funeral home for the final viewing.

In a country southern accent, Mrs. Truluck said to me as I led her by the arm up to her son’s casket, “Wasn’t my Jay a beautiful boy?”

“Brace yourself, Mrs. Truluck,” I warned. “He’s not beautiful anymore.”

When she saw her son’s AIDS ravaged face, she collapsed into my arms. Tim and I left her and Jay’s devastated sister weeping openly over his casket as we retreated to the rear of the chapel.

Tim was furious and said, “I’d like to slap the hell out of both of them. They should’ve been here with Jay.”

“Tim, they’re southern just like you and me. They were just being true to how they were raised. Surely, we can understand that,” I said.

“I hate when you go all sentimental and Christian on me,” Tim said. “That’s exactly what’s wrong with your writing.”

Tim never liked anything I wrote. As an English teacher, he insisted the prose be spare, unadorned, unflashy, but hard-hitting and severe. From the beginning of my career in Beaufort, Tim found my writing over-caffeinated, pretentious, and blowsy.

“Have you never heard of the eloquence of simplicity, Pat?” Tim Belk would say.

I would answer, “I’m after something else, Belk. The elegance of grotesque overwriting and egregious excess.”

“But you’re making me a character in all your overblown novels,” Tim said. “I’m a man of Shakespearean depth, but I get a hack like you to tell my story.”

“Therein lies your tragedy, Belk,” I would say.

“You’d be a much better writer had you only been born gay,” Tim said.

“Therein lies my tragedy.” We could always make each other laugh.

In 1996, Tim began to die in earnest. On my book tour for Beach Music we met at the Washington Square Bar and Grill and openly discussed his death for the first time. He now weighed less than a hundred pounds and had assumed that haunted, skeletal look of all AIDS patients at the very end. He held my hand as we talked and his grip was shaky. A resignation to the inevitable had entered his voice when I had an idea.

“Let’s go on a final trip, Tim. It’s on me and we’ll go first class all the way. Doubleday is sending me to England and Ireland soon and we can have one last legendary good time together.”

“My bags are packed,” Tim Belk said and that next spring over the Atlantic Tim and I  toasted our years of friendship with a bottle of champagne. By then we had taken many trips together and found ourselves companionable in travel. Now, we promised to have the time of our lives and make this trip famous among all our friends. When we got off in Heathrow, there was an announcement on the loudspeaker for Tim to report to the Delta message center. Tim’s doctor from San Francisco ordered Tim to report to a London hospital and Tim became one of the first human beings on earth to be put on the “cocktail,” the intricate series of drugs that stopped the epidemic in its tracks. To us, that trip took on mythic proportion. We had our finest time together as friends on this earth. Tim always referred to it as the trip that saved his life.

toasted our years of friendship with a bottle of champagne. By then we had taken many trips together and found ourselves companionable in travel. Now, we promised to have the time of our lives and make this trip famous among all our friends. When we got off in Heathrow, there was an announcement on the loudspeaker for Tim to report to the Delta message center. Tim’s doctor from San Francisco ordered Tim to report to a London hospital and Tim became one of the first human beings on earth to be put on the “cocktail,” the intricate series of drugs that stopped the epidemic in its tracks. To us, that trip took on mythic proportion. We had our finest time together as friends on this earth. Tim always referred to it as the trip that saved his life.

Tim Belk did not die of AIDS. On October 21, 2014, I received the news of Tim Belk’s death when I was speaking at the Southern Festival of Books in Nashville. He had gone into toxic shock after a kidney infection and died in the hospital. His friends mourned him all over the world. But our tears mingled with bursts of laughter and an affection that was borderless and somehow sublime. He changed my whole life and the way I saw the whole world. I was lucky to know him, to love him, and to be transformed by his love of me. I did not cry until I spoke with Laura and Matthew Ringard, the friends he had met through me only three years before. They were devastated and through their loss I felt myself collapse. As I rode through the bomb plant between Aiken and Allendale, I fell apart.

His light has gone out, but the music plays on.