The Beaufort native will appear in the Pat Conroy Literary Festival on November 7

The Beaufort native will appear in the Pat Conroy Literary Festival on November 7

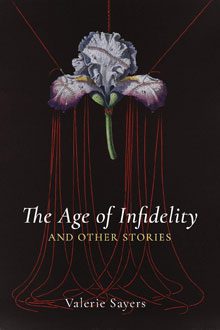

With six acclaimed novels already to her credit, Beaufort native Valerie Sayers has recently released a first collection of stories, The Age of Infidelity, which span from the Due East in the 1960s (the familiar southern setting of much of her fiction) into speculative visions of the future. Once a high school psychology student of famed writer Pat Conroy, Valerie was inducted into the South Carolina Academy of Authors, the Palmetto State’s literary hall of fame, in 2018 (just as Conroy had been honored thirty years prior). She will return to Beaufort, albeit virtually, as a workshop instructor and presenting author in the 5thannual Pat Conroy Literary Festival, this November 7. (Learn more about the festival in the full-page ad in this issue or at https://conta.cc/3izeBPh.)

Valerie discussed all of that—plus some vital lessons she has learned from her students and teachers—in this recent email interview.

Jonathan Haupt: The Age of Infidelity is newly published by Slant Books. How did these 11 stories, written over time, come together as a collection?

Valerie Sayers: They evolved over many years–almost twenty. Each one came upon me suddenly, and I wrote the first drafts quickly (then fussed with them for months to come). I was perfectly happy to publish them individually. It wasn’t until I saw the infidelity thread that I thought I might put these eleven together as a collection; as I pieced them side by side, and thought about stories I’d published a long time before, it tickled me to think about how variously and persistently that theme played out in my work.

JH: What are we talking about when we talk about infidelity in the context of these stories?

VS: Sexual or marital infidelity is an explicit concern in some of them, including the title story, but some of the other variations interest me more: in that title story, for example, the narrator also has to choose whether to be faithful to a suffering mother apparently beyond reach. In other stories, characters have to choose whether to be faithful in the religious sense, or in the political sense. At the end of “Should I Be Afraid?,” the protagonist has to decide whether he can be faithful to a weaker person when his own life is on the line. The futurist stories are all interested in whether human beings can be faithful stewards to the natural world.

JH: Several of the stories wander deeply in speculative, specifically into futurist fiction. What other writers do you read or teach in this genre? And what sparked your interest in writing these tales?

VS: In the last couple of decades, I’ve become fascinated by how many of the literary writers I admire were trying their hands at futurist work. Margaret Atwood, with her MadAddam Triology, is probably the best-known example, but I was also intrigued by what Colson Whitehead, Zadie Smith, and Chang-rae Lee were doing. I decided to teach a course called “Writing the Future,” which led me to consider more literary writers–Karen Russell, Jennifer Egan, Junot Díaz–who were moving back and forth between contemporary and future settings, as well as to some classic science fiction I had always avoided like the, well, plague. Recently, I was entranced with Gish Jen’s futurist baseball novel, The Resisters.

JH: The writer Jill McCorkle said once on a visit to Beaufort that, “writing a short story has as much in common with writing a novel as writing a novel has in common with baking a cake.” More recently, George Singleton compared writing a novel to cooking a five-course dinner, whereas a short story is like focusing all of your attention on making a really good side dish. Food metaphor or otherwise, how would you compare writing short form and long form fiction, as a writer who excels at both?

VS: Thanks for the lovely compliment. The food metaphor’s never occurred to me–and I have to say, I don’t think a good story is a side dish, I think it’s perfectly capable of holding center stage (as long as we’re cooking, might as well mix that metaphor). Writing stories and writing novels, though, are absolutely different experiences and, as Jill McCorkle says, nothing like cooking. The ideas for both stories and novels come to me suddenly, or so it seems. The scope of the idea (or the image, or the snatch of dialogue, or the narrative voice) determines which form I’ll tackle, and I usually know that right away too. For a novel, the themes have to be big and complex, capable of holding my curiosity for years. For stories, I often feel a pressing immediacy: I have to get the whole of this down right away. But often, characters or themes from one story crop up in another, and then I have to wonder whether I’m actually circling a novel.

JH: From past conversations, I recall that you once accidentally signed up for a poetry class and that you still turn out a poem once a year or so. What did that class—and continuing to practice the craft of poetry—add to your prose writing style or process?

VS: Good memory! Actually, everyone in the class but the professor had signed up for fiction writing. The registrar had listed the course title wrong. We all stuck with it, though, and the professor, Bob Nettleton, was delightful. He’d been an engineer but changed careers because he was smitten with language. I’d written poetry since I was a kid, but he really gave me permission to take pleasure in it, to laugh at it, to roll around in language and not worry about getting dirty.

JH: Several stories in The Age of Infidelity take us back to Due East, the fictional southern small town that is both setting and character in most of your novels as well. What can you tell us about the origins of Due East in your imagination? Does it now feel like a place generating its own stories for you to chronicle or as a space which you motivate along as creator and storyteller?

town that is both setting and character in most of your novels as well. What can you tell us about the origins of Due East in your imagination? Does it now feel like a place generating its own stories for you to chronicle or as a space which you motivate along as creator and storyteller?

VS: I write about Due East, that thinly-disguised Beaufort, because I have spent my entire adult life elsewhere, pining for home. When I was a young writer, I was heavily under the influence of Faulkner and wanted my own moral universe. I was also standing in Joyce’s shadow and thought I might reconstruct Beaufort the way he reconstructed Dublin, from a distance. I stole the name Due East from my brilliant writer friend, Mike Witkoski, who was of course from Beaufort and, if anything, more obsessed with Faulkner and Joyce. I write less about Beaufort now because it’s changed so much since I lived there; I don’t want to pass off my nostalgia or my longing as authenticity.

JH: Your story “Tidal Wave,” which was recognized with a Pushcart Prize, is written mostly (but not exclusively) in the collective voice of “we.” What prompted you to tell this story in this way?

VS: I often ask my students to write in that collective voice as an exercise, and one day I thought I’d better try it out myself. It’s a great voice to suggest a herd mentality, and since “Tidal Wave” is about a group of high school girls, it’s the perfect voice. Originally, I planned to have the whole story told by the “we” chorus, but eventually it became clear that one of those girls needed a solo, and so her voice bursts out, if only briefly. By the end of the story, we realize she’s never had the courage to break free of that pack.

JH: “Tidal Wave” centers on Due East High School. After your graduation from the real Beaufort High School, you headed off to New York City. What were you looking for? And what did you find?

VS: Like many young folks headed to the big city, I was looking for razzle-dazzle. I wanted to be an actor, an ambition which lasted about seven minutes in the city. I was looking for plays and art and music, and since it was the Sixties, I was looking for the counterculture. I was also looking for intellectual challenge–I found plenty of that-–and what I perceived to be more enlightened views about race. When I left Beaufort, integration was proceeding slowly and with plenty of tension. I discovered, to my surprise, that New York City harbored plenty of racial bigotry, too. That was a good lesson. When I graduated from college and returned to Beaufort to teach for a year, some of my older white students at what we then called Beaufort Tech (now Technical College of the Lowcountry) told me that they’d been brought up to defend segregation but had changed their minds completely. I remember one of them saying: “We just didn’t know any better.” That was another good lesson.

JH: At our 5th annual Pat Conroy Literary Festival, you’ll be reading with fellow South Carolina Academy of Authors honorees Andrew Geyer and Pam Durban. When Pam has visited us before, she has spoken about the idea that most writers have “required subject matter,” meaning themes they return to again and again. What’s your required subject matter?

VS: Religious faith and questioning. Political philosophy. The impact of geography, of the natural world. Once I start listing my required subjects, I could go on all night, but maybe those three sum it up best.

JH: How did your teaching life begin? What do you find most challenging and rewarding about guiding burgeoning writers on their paths?

VS: Since I’m one of seven siblings, and an insufferable know-it-all, my teaching life began at home. At Beaufort High School, I was asked to assist the teacher in a freshman French class, and I got a kick out of telling freshmen what to do, almost as much as I enjoyed telling my little sisters and brother what to do. After college, I taught five different subjects, from economics to human relations, at Beaufort Tech. In graduate school, I tutored, and as soon as I had my degree, I began teaching composition in a community college, then an engineering school. Later, I taught fiction writing at N.Y.U. and now of course at Notre Dame. So it feels as if I’ve been teaching pretty much my whole life. What’s most challenging is how many hours a day it takes to read student manuscripts carefully and respond to them fully. What’s most rewarding is how much I’ve learned from my students, especially about taking risks. These days I try not to tell my students what to do, at least not so insufferably.

JH: To circle back around to high school again, you were a psychology student of Pat Conroy’s during his two years of teaching at Beaufort High School, following his graduation from The Citadel and before his famed year of teaching on Daufuskie Island. What lessons from that experience do you still carry with you as writer, as teacher, or as good citizen of the realm?

VS: Pat was a performer. He worked the room, made eye contact, provoked us, cracked cheesy jokes, revealed himself. He gave the impression that he knew exactly what he was talking about, whether he did or not. And he liked to surprise us. Like Gene Norris and Millen Ellis, who taught him as well, he was an idiosyncratic teacher who trusted his gut more than any lesson plan. The idea of giving students a performance stays with me, though I’m not as gifted or as fearless as Pat was. But even more crucial was the way Pat genuinely enjoyed us–I think that’s hugely important, that teachers take pleasure in their students, and make sure their students know it.

Jonathan Haupt is the executive director of the nonprofit Pat Conroy Literary Center and coeditor of Our Prince of Scribes: Writers Remember Pat Conroy.