Author to Appear in Conversation with George Singleton for the Conroy Center in Free Virtual Event

Author to Appear in Conversation with George Singleton for the Conroy Center in Free Virtual Event

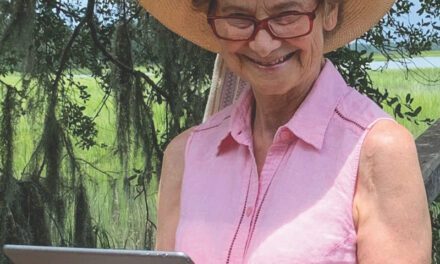

By Jonathan Haupt

Acclaimed writer Ron Rash as been celebrated as an “Appalachian Shakespeare” for the depth and timelessness of his writing. An accomplished poet, short story writer, and novelist, Rash has been honored with the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, the O. Henry Prize, the Sidney Lanier Prize for Southern Literature, and with inductions into the Fellowship of Southern Writers and the South Carolina Academy of Authors. His recently published story collection In the Valley includes his first novella, a return to the world and characters of his PEN/Faulkner finalist and New York Timesbestselling 2008 novel Serena. Rash will appear, along with fellow award-winning southern storyteller George Singleton, in a virtual event hosted by the nonprofit Pat Conroy Literary Center on Thursday, December 3, at 6:00 p.m. Free registration is open through the Center’s website, PatConroyLiteraryCenter.org, and Facebook page. The video recording from the event will also be available afterwards on the Center’s Facebook page and YouTube channel.

In this recent interview, Ron Rash shared the challenges and rewards of writing his first novella and revisiting Serena Pemberton, and he discussed the themes and lessons that permeate his new collection and his larger body of work.

Jonathan Haupt: By my count, you have seven novels to your credit, almost as many poetry collections, and now what is both a seventh story collection and, therein, a first novella. What led you to want to undertake a novella?

Ron Rash: I’ve always admired that form. It was also a form I hadn’t written yet, and yet some of my favorite books are novellas—a couple of Chekhov’s stories, and Faulkner’sThe Bear,for example. But one book in particular knocked me out a couple of years ago, that was Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams.It showed me what was possible in a novella. So I wanted to see what I could do. The I worked for three years on that novella, the length of time it would have taken me to write a novel. I didn’t want it to be just an appendage to Serena,either. I hadn’t accomplished that goal of making it a work wholly its own until I came up with the structure of the story with the exodus of the animals from the valley, like they’re fleeing from the ark, from what had been their home. Then I finally felt like a had written a full experience as a novella.

JH: The novella “In the Valley” heralds the return of Serena Pemberton, the grand villain of your bestselling novel Serena, a character you have confessed to fearing yourself. What prompted you to return to Serena and her supporting cast of characters in the North Carolina wilderness?

RR: Part of the reason I wanted to go back to that world of Serenawas I was always intrigued by the character of Ross in the novel. He saw things deeper than others around him, and I always wondered why. He seemed unexplored to me. I had a sense that something had left him devastated, but that he was still capable of sacrificing for a sense of greater good in an act of courage, as we see him do in this story.

My environmental concerns inspired this return too. What has happened with deregulations in the last few of years is something that hasn’t been talked about enough. The EPA has been pretty much destroyed, and I wanted to tell a cautionary story that would remind people just how quickly our natural world can be lost to us.

JH: In revisiting these characters who were established and familiar to you, were there any particular rewards or challenges for you?

RR: One part I had such fun with, in writing the loggers, was that I ran an iambic pentameter line through almost all of their speech. I thought that would be interesting, to have this rustic Appalachian dialect written in Shakespearean form. That was quite an undertaking, too, because I didn’t want it to sound forced or artificial. I wanted the reader to sense that there was an authentic rhythm there, even if the fullness of it goes unnoticed. It gave me a chance to try something new with these characters, and I think it comes across as I hoped.

I had fun with the opening too. I knew that if Serena was going to return to the page, she had to make a grand entrance. I wanted to have her fly in like a Valkyrie, almost like Hitler in that propaganda film A Triumph of the Will.So I wrote this opening in that Wagnerian scale, with her plane coming out of the clouds like a god, swooping back into the reader’s consciousness. And then when she speaks for the first time in the novella, she is articulating her ambitions to see that the “world and my will are one,” a little play on “one” and “won.” Then there was no doubt that Serena had returned.

JH: You’ve spoken about how your characters can take hold of their own stories and let you know they’re not done. Some of your stories began as poems, and some of your novels began as poems or stories. Serena began her literary life in a short story, then demanded her own novel, and has now warranted your first novella. Is this character done with you?

RR: I surely hope so.

JH: The novella and the nine short stories are an inviting mix of cautionary tales and hopeful glimpses into the capacity of the human spirit to transcend difficult circumstances. You open with epigraph from Dietrich Bonhoeffer about endurance through suffering. Is that a thematic lens through which we should view the collection—as stories of faith, often tested and occasionally rewarded?

RR: As Ross does in the novella, there are people who, in difficult times, stand up when they need to and when they might not expect that they still can. Bonhoeffer is a quintessential example of that. Every time I write a collection of stories, I think about cohesion, about how the stories speak to each other. These are all stories about people being tested in extreme situations and discovering their faith, bravery, and endurance. Faulkner said once that he thought most people were “a little bit better than their circumstances give them a chance to be.” I believe that. I was putting this book together when the pandemic hit, and I wanted to remind people of our capacity to endure, and also to “love and remain true,” as Bonhoeffer says.

I started off with “Neighbors” in the collection for that reason, as a warning of what can happen if we become too tribal, too partisan, as we have been. That’s historical fiction, but it’s about what’s happening in our present and what can happen if we’re not careful.

JH: There’s also a reference in “Neighbors” to the Shelton Laurel, the site of the Civil War massacre you described in The World Made Straight, and a reminder that you’ve shared a similar warning once before.

RR: That’s one of the sad things about what happens when the lessons of history go unlearned: you can see similar tragedies happening again and again, as in Kosovo, in Rwanda, in Cambodia. But one of the great gifts of literature is the capacity to remind us of these lessons of our past in new ways, in the hopes that we might yet see the weight of our actions and alter our course.

JH: I was particularly struck by your story “Last Bridge Burned,” which is also about a kind of course correction, albeit on a more individual level. There’s an unlikely pairing of hardscrabble mentor and precariously poised student (both roles broadly defined), which is something familiar in your work, most notably with Leonard and Travis in The World Made Straight, and even to some extent in “Ransom” in this same collection. Where do these kinds of encounters and pairings come from for you as writer?

RR: I truly believe teaching is a calling. I’ve been a teacher for a long time now, and I’m still a student as well. I’ve seen the impact it’s had in my life, and I honor that. In these stories, I’m exploring what we might do when given the opportunity to care, to shepherd another life through a tough passage. Flannery O’Connor talked about those moments when the character surprises us, which happens in our lives too. That story, “Last Bridge Burned,” started off with an imagine of a gas station with a light on, and it was late, and I knew something unexpected was going to happen between two characters who would never otherwise be together. And what happens, what Carlyle does with this young singer, Sabrina, in his care, is that great mystery of human beings: that we can still surprise ourselves. I don’t know that he could even articulate why he helps her as he does, and that’s the beauty of that moment. What I try to do, here and in all of my writing, is bear witness to the wonder of our human experience without any moral didacticism intruding, respecting the reader’s ability to interpret reason and meaning. Literature works best in the gray, instead of the black and white.

JH: The natural world in your writing is always, at once, gorgeous and dangerous, a world in jeopardy and also full of jeopardy. What lingering lessons do you hope will guide your readers in their own interactions with nature after reading your stories?

RR: When I write about the natural world, I try to be as descriptive as possible because I think people have to notice the world before they can care for it. Particularly now with all of our technological distractions. Some of the best nature writing is where you see a writer observing that world and, simply by doing so, saying that there is something of value here. I strive for a moral complexity of viewpoints in my writing too, because it’s easy for outsiders to say what we should or shouldn’t allow to impact our natural world without the context of the human lives and livelihoods involved. Obviously, I’ve got my leanings, but I am first and foremost a witness to this conflict between conservation and industry. I tell my students if you can upset people on the left and right, then you’ve probably done your job as writers.

JH: In the Valley came out amid our ongoing pandemic. In this anxious, uncertain, easily distracted time of ours, are you finding that readers are more open to reading short fiction?

RR: People have been very responsive to short stories this year, and part of it is that they are reading more in general. A number of people I know who do not necessarily identify as being big readers have gone back to books and stories during the pandemic. I’ve always thought that short stories were a great contribution from American writers to world literature, under any circumstances. Go back to Poe, for example. His influence on European writers was significant. And, as you get into the 20thcentury with Faulkner and O’Connor and Hemingway, all of those writers—it’s something that we seem to do well. It’s my favorite form, so it’s always what I enjoy most as a writer. I think it’s the hardest form to do well, too, but the challenge is part of the fun of it.

In terms of the reception of In the Valley, I think I’ve been very fortunate. And this one has just about as beautiful of a cover as I’ve ever had. I’ve had such a good response from other writers too, and that’s always a good sign when it happens.

JH: Speaking of other writers, you’ll soon be appearing on screen for our Conroy Center with our pal George Singleton, who recently published a masterful edition of collected stories, You Want More. How would you describe your friendship? And what’s it been like to do a few of these virtual book tour events with him?

RR: George’s new collection is great. It’s a big book, which reminds us of how much he’s done and how good of a writer he is. When we get together—well, every good comedy team needs a straight man, and that’s been my role. I get abused, but we have fun together. We’re two guys giving each other a little grief, and somehow that’s been very entertaining for our readers. I’m a few years older than George. I was a sophomore in college and he was still in high school when we first met as track-and-field athletes at Gardner Webb, where I was. We got to know each other as runners, and then it must have been 15 years later when we met again at Frances Marion. And it’s been an interesting friendship ever since. We started out together, a bunch of us writers, and struggled for years, sending out work, comparing rejections. It’s kind of been an exercise in attrition. Others just kept dropping off, and one day, George and I looked around and saw we were about the only ones still standing. It’s been fun to get to share our stories together in these online programs, and it will be an honor to do so for the Conroy Center. Just don’t believe anything George says.

Jonathan Haupt is the executive director of the Pat Conroy Literary Center and co-editor of the anthology Our Prince of Scribes: Writers Remember Pat Conroy.