Three writer/educators of three different generations discuss the state of literature today – reading it, writing it, publishing it, and teaching it – in anticipation of Beaufort’s second annual Short Story America Festival and Conference.

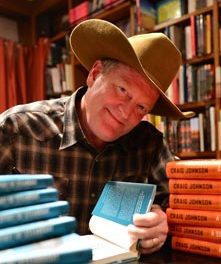

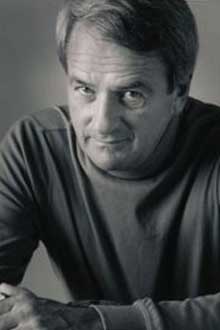

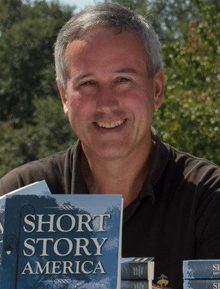

Richard Hawley Tim Johnston Mathieu Cailler

While preparing to cover Beaufort’s second annual Short Story America Festival and Conference, I read The Headmaster’s Papers, the 1983 breakout novel by festival headliner Richard Hawley; it gently but profoundly shook me up, as only a great book can. A few months earlier, I’d read festival founder Tim Johnston’s new collection of short stories, also very powerful. I met presenter Mathieu Cailler at last year’s festival (he took the prize for Best Short Story), and we became friends on Facebook, where I’ve had the pleasure of reading several of his wonderful poems. While contemplating a Festival article, it occurred to me that Hawley, Johnston and Cailler are writers from three different generations . . . who also happen to be teachers. I thought a discussion about the state of literature today – as seen from their various perspectives – might yield some interesting insights. The three gentlemen graciously agreed to participate in my little “roundtable,” and questions went out to their respective inboxes – Rick’s in Vermont, Mat’s in California, and Tim’s right here in Beaufort. I think you’ll find their responses fascinating. I know I did.

– Margaret Evans, Editor

1) Do people still care as much about books as they once did?

Richard Hawley: Without a doubt they do. I do; my reading and writing friends do. Whether as many people today still care deeply about books, and are children embracing literature as prior generations have done, are good, open questions. The biggest variable is cross-generational influence. Book-loving parents and teachers are infectious. Every loving parent I know reads regularly to his/her younger children, and those children bear that love, and they read.

Tim Johnston: People still care about books. The question, unfortunately, is whether people still care about literature. Civilization has needed literature, not just books, since long before the printed page. Stories that matter to the soul and character of the reader have been told and interpreted since the first humans began to communicate through language. Truth and introspection intersect within the mind of the thinking reader, but if the thinking reader is not finding literature out there in the sea of bestsellers, then the level of caring about books may be diminishing with every generation that lives in the era of easy entertainment (television, computers, smart phones and the like, which are wonderful devices when we control them, but not when we allow them to control us).

Mathieu Cailler: Yes, I think they do. But multi-tasking seems to have become a national pastime and when a person is reading, he or she is not able to do anything else. That’s what I love most about it, but what some probably find most difficult.

2) What would you tell a student who came to you for advice about pursuing a career as a writer?

Richard Hawley: I tell them what I am convinced is the truth: not to worry. If they are meant to be writers, nothing will stop them. Poor prospects for publication won’t stop them, dismissive criticism won’t stop them, terrible conditions and time constraints won’t stop them. Real writers can’t stop themselves. They work in poverty, in pain, in a sea of rejection. I think I realized I was a writer when I was a headmaster of a busy school and had far too much to do in a day than was possible. I used to hope that a story idea or a poem idea would go away so I wouldn’t have to write it. The ones that wouldn’t go away got written. Real writing will be pulled out of you, one way or another. It can be like floating downstream or like a breached birth, but out it will come. Real writing, anyway.

Tim Johnston: The first thing I would say: Always be reading. As the saying goes, “There are great readers who are not great writers, but there are no great writers who are not great readers.” Second, I would advise the student to decide what he or she wants from a writing career. If the field is fiction, does the student want to be rich and famous, or does the student want to write something that might matter to the soul of the reader? It is not often anymore that the two go hand in hand, and that is not the fault of the writer. For every J.K. Rowling who writes meaningful stories and also gets rich, there are hundreds if not thousands of quality writers who cannot find enough of an audience to pay the mortgage.

Mathieu Cailler: I would tell him or her to go for it. I really believe that if a person can and wants to write, it is his or her duty to do so. I recently read that when a tree is planted, the carbon dioxide absorbed is the equivalent of taking 25,000 cars off the road, and I think that is what a writer does. Each story, poem, essay, memoir, play, and novel written lightens strife and isolation, as well as promotes understanding, compassion, and thinking.

3) Discuss the state of publishing today. Is it easier or more difficult for a new writer (or even a seasoned writer) to be published?

Richard Hawley: It’s a bewildering mess. New printing technology and the digital flow of texts across social media are causing nothing less than a reconsideration of what a “book” and what “publishing” are. I advise people to do whatever they can to get their work in front of others who might be interested. That, after all, is the point of writing, commercial publishing be damned. I have published books in every possible way, with big conglomerate houses and with small, principled independents. I have put out a piece or two on my own. My goal is simply to connect with readers, really connect. When that happens and someone lets you know, it is a happiness passing all understanding.

Tim Johnston: I have heard it said by a number of veteran authors that if they were starting out today, they would have a very difficult time getting published in any life-supporting monetary way. Publishing is dominated by capitalism’s number one philosophy: maximize profits, and minimize risk. When the best way to do that today is by sticking with the established authors and not taking big chances with new writers, you unfortunately see authors with great potential forced into 50-hour-a-week jobs away from writing, many of whom could have made it, say, 50 or 60 years ago before computers, television, the internet and smart phones arrived to compete with the good book for the consumer’s entertainment dollar. So, write because you feel called to writing. Write because you have stories to tell, and to leave behind. If publishing happens, great. If not, bring it out yourself. But get your work out there if you believe in it.

Mathieu Cailler: It seems there are more avenues than ever for publishing, but I do not know if it has gotten easier. It is still just the writer and the blank screen, and I am not sure I’d want it any other way. I’ve had the good fortune to have my stories and poems published in numerous literary journals, and am currently wrapping up my first collection of short stories, so I’ll probably have a better understanding of the book-publishing world in the months to come. And now I’m sweating.

4) Today’s students have no memory of a time before the Internet and other media technologies shattered the world’s attention into a thousand pieces. Where do books fit in for them? What are the challenges of teaching literature to this generation?

Tim Johnston: How do you get young people to the stage of becoming lifelong readers and thinkers? You must expose them to books and stories which engage them. The best books and stories engage every generation. While Moby Dick loses many young readers, The Catcher in the Rye and A Separate Peace do not. So teach the latter two, which young readers find relevant and interesting, and don’t teach Moby Dick until the young reader is ready and willing to take it on. This is why I’ve always liked teaching short fiction in literature classes, from American Lit to World Lit. Students enjoy stories that can be read and considered in one sitting. As a result, they are ready for class discussion, for development of analytical and critical thinking, because they have completed AND enjoyed the reading. It’s interesting that Anne Serling is here for the Short Story America festival, because I think that The Twilight Zone is a great vehicle for teaching literature, and writing about literature, to students.

Mathieu Cailler: Sometimes my students look at books the way I might a musket, but yes, young people still read. That’s where I think a series like Short Story America could be incredibly helpful. A student can have an artistic experience in less than thirty minutes. Most of the time when I teach short stories, students say they’ve never read one. That needs to change.

5) A lot has been written lately about the “death of the English major.” We hear that this is a disappearing breed, that the “real world” has no use for them. Do you think there’s still a case to be made for the intensive study of English in college?

Richard Hawley: I suppose, but I think it matters more that people in college get exposed to great literature, whether from peers or from any number of academic slants. I am also not sure that being an English major today is likely to foster the passionate reading that I’ll bet you are referring to. I would not want to be an English major under the influence of deconstructionists, semioticists, hermeneuticists, and others whose aim is to detach texts from what writers intended to say – and what they really do say when you read them, instead of performing distracting, rarefied operations on them.

Tim Johnston: People need self-nourishment, beyond food and fun and travel and watching, and they need to believe that it matters that they are breathing the earth’s oxygen right now and not a hundred years ago or a thousand. The people who think about that a lot tend to seek out stories, and plays, and poetry, and music which is both beautiful and inspiring or has something to say to the soul of the listener. Often these people want to learn to express themselves, to communicate ideas and opinions and stories and histories with vivid clarity and often the power of persuasion. Sometimes these people become English majors, and soon find out that there is an enormous library of life-enhancing literature and history and philosophy out there, proving without a doubt that the meaning of life is that love and conflict and truth and justice and friendship and sacrifice are miracles in this universe, miracles to be shared and shown and imagined and dreamed about. I began to learn about those miracles as an English major at Davidson College, and no matter what I have ever done to earn a dollar, I will always be the better for having done so. I still recommend it highly.

Mathieu Cailler: The death of the English major . . . wasn’t that an Arthur Miller play? Don’t we all leave college unfit for a job in the real world? I think that’s the problem, actually. A person goes to school to get an education, to be exposed to a variety of subjects, not to get a job. There is most definitely a case to be made for the English major. Most jobs entail writing, communicating, reading, and a deep examination of material—all traits of the English major.

6) Who are some of your favorite writers and/or greatest influences?

Richard Hawley: Impossible to convey in a confined space–and today’s list may be contradicted tomorrow. Today I am mad for novelists Anthony Powell, Edward St. Aubyn, Dickens, Robertson Davies, Evelyn Waugh,Mark Helprin, John Updike, Philip Roth; story writers Alice Munro, V.S. Pritchett, William Trevor, Margaret Atwood, John Cheever, Carol Shields; non-fiction writers Paul Theroux, Henry David Thoreau, Malcolm Gladwell, biographers Humphrey Carpenter, Blake Bailey . . .

Tim Johnston: As far as classic influences, I love the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Raymond Carver, Flannery O’Connor, Ernest Hemingway’s short stories, many short stories by Stephen King, and the on-screen work of writers like Rod Serling, who found a way to bring stories that mean something, and are even instructive about how to be and not to be, to audiences which might never have been touched otherwise by stories. Today, I read short fiction by fellow writers of the form, including those who are attending our festival, and I read a ton of history and philosophy in hopes of improving my understanding of the human condition, the quest for the truth, the history of societies and cultures and the ever-present conflicts which make life difficult and yet so worthwhile.

Mathieu Cailler: I love people who find the interesting within the mundane: Raymond Carver, Alice Munro, Chekov, Hemingway, Grace Paley, and Naguib Mahfouz. These days, I’m reading Ha Jin’s short-story collection, The Bridegroom, which is as beautiful as it is thought-provoking.

7) What are you thoughts on the controversial new Common Core standards?

Richard Hawley: The motive is good, the particular iteration of the standards so far is a bit uneven. Teachers expected to administer them are not entirely clear what is expected, and the assessments need to be reviewed, clarified and improved. My prayer for the Common Core, if universally adopted, is that reaching the standards is assessed at the end of secondary schooling, not along the way, so that teachers can devise multiple personally comfortable ways of teaching to them and that school is relieved of being glorified test preparation.

Tim Johnston: I do not believe in standards that are not genuinely incorporated into learning. There is a big difference between knowledge and understanding, and I have yet to see “standards” established which really underscore the human need to UNDERSTAND and to be PASSIONATE about something worthwhile in learning. For me, the best education is one that presents a breadth of opportunity for students to pursue their passions, and to discover those passions in the first place. Any system or set of standards that bogs education down in the interest of one size fitting all is not an enhancement of learning as understanding. No Child Left Behind was a bureaucratic failure from the first day, as are state-level efforts to tailor tests to demonstrate “improvement” in the eyes of the bureaucratic behemoths which govern schooling. I am not well-informed about Common Core, as I have been out of the field of education for four years, but my suspicion is that Common Core does little to enhance the capacity for each student to discover his passions and pursue them with the invigorating guidance of dedicated and talented educators.

Mathieu Cailler: Common Core Standards are tricky. On one hand, a student should master things in a particular grade level; however, it becomes increasingly difficult to define mastery. Is knowledge something that can ever be mastered? I would like to see an expansion of criteria to define understanding: projects, tests, as well as student portfolios.

The Short Story America Festival & Conference will be in Beaufort September 26 – 29. To learn more and see a full schedule of events, go here.