A candid (only-slightly-censored) conversation

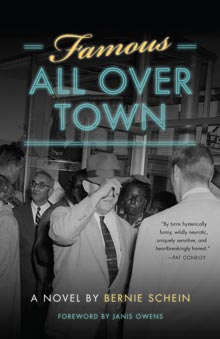

A candid (only-slightly-censored) conversation  with Bernie Schein about growing up Jewish in Beaufort, insiders and outsiders, and his new novel Famous All Over Town.

with Bernie Schein about growing up Jewish in Beaufort, insiders and outsiders, and his new novel Famous All Over Town.

By Margaret Evans, Editor

I showed up on Bernie Schein’s front porch with a list of questions and a plan. This was a mistake. Despite his repeated claims that he’s OCD, strict adherence to a plan is not Bernie’s strong suit. (Not someone else’s plan, anyway.) Interviewing Bernie is more like hopping a train of thought – his – then holding on for dear life as it careens down one track after another, sometimes jumping the rails entirely. It’s an exhilarating ride and you cover a lot of ground. Just don’t kid yourself that you’re the engineer.

And know that there will be detours. And delicious distractions. Only ten minutes in, Bernie’s neighbor appeared on the porch with homemade cupcakes. (“I heard voices over here and thought y’all might need a snack.”) This, after all, is Beaufort, South Carolina, the small southern town where Bernie grew up . . . the same town that inspired his new novel, Famous All Over Town. Beaufort’s changed a lot since Bernie was a boy, but some things are timeless in a place like this: Good porches still make good neighbors and people still love cupcakes.

Bernie spent over an hour musing on my first question – detours, remember? – and as much fun as we were having, I had to get tough and move on. When his answer to question #2 began sprawling in similar fashion, I decided to chuck my list altogether and go with the flow. I recorded over three hours of conversation, nearly broke my face laughing, teared up a few times, and needed a nap when I got home.

The following interview has been judiciously edited for space, coherence, and excessive profanity . . .

Margaret: Tell me a little about the germination of Famous All Over Town.

Bernie: A long time ago I worked on a memoir about growing up Jewish in Beaufort, and I’d written articles about it, too – in particular, one that was incredibly controversial in Atlanta. It was for the Sunday Weekly supplement in the Atlanta Journal & Constitution. I wrote about my experience as a small town Jew growing up in the Bible Belt, and I thought I was celebrating it! I said things about the Jewish/Southern culture clash, like, “Show me an easy-going Jew, and I’ll show you an ulcer,” and “Show me a Jew with a moose head on his den wall, and I’ll bet you his little girl has already peroxided her hair and had a nose job…”

Margaret: It sounds like you were saying stuff about Jews that a Jew should be allowed to say!?

Bernie: Well, I thought so! And the small town southern Jews loved it. But the city Jews? The big voices in the Jewish community, the spokespeople? They absolutely hated it. They called me an anti-semite! One guy wrote to say I gave him indigestion. I wrote back and said, “Oh, come on… you know you had that already. It’s a Jewish condition.” Anyway, I was shocked, Margaret. I was hurt and I was angry. Because they were telling me I wasn’t Jewish! But the whole point of the article was that, for the southern Jew, because of assimilation, there is a trade-off. I didn’t know what a schmuck was growing up, or a mensch or a schlemiel. I didn’t eat lox and bagels, I ate burgers. Okay? So, there was a difference.

Margaret: So, you wanted to set the record straight? Sort of expand on your experience of growing up Jewish in a small southern town?

Bernie: Right. Because the truth is, I felt special growing up Jewish in a small southern town.

Margaret: You didn’t feel persecuted? Didn’t think people looked down on you for your Jewishness?

Bernie: (laughs) No, because they didn’t. That was a Yankee fantasy. The northern white was prejudiced against Southern whites, okay.

For example, when I went for my grad school interview at Harvard in 1970, the cab ride from the airport took me through Roxbury – and I had never seen a ghetto. I couldn’t believe it; I was stunned! And the whole way over, the white Irish cab driver was using the worst racist language I’d ever heard, just a running diatribe. So, I get to Harvard, and the guy in the admissions office looks in my folder, sees I’m from Beaufort, SC, and says, “How can you people let that kind of racism go on down there?” And I said, “I just rode through Roxbury. How can you?” And he hated my guts for saying that.

Margaret: But you still got in.

Bernie: Well, the others liked me, I think. I was dumber academically than anybody  they’d ever seen, but I wrote better than the high-test-score, straight-A students. Their stuff was boring.

they’d ever seen, but I wrote better than the high-test-score, straight-A students. Their stuff was boring.

Here’s another example of what I’m talking about. A man from up north once told me there was nothing I could tell him about the racist South that he didn’t already know. I said, well, I think there are three things, at least:

#1) My grandfather found a black baby on the railroad tracks near Yemassee in 1896 and adopted him. The black nanny he’d hired to take care of his own family cared for this baby. When she left a few years later, she took the boy with her. Nineteen years after that, a black man came into my grandfather’s grocery story to rob the place and shot my grandfather dead. My father (16 at the time, and living in the back of the store) heard the shots, ran in and grabbed the gun, but the man escaped. Reverend Meyers, a black preacher who lived near the store and loved my grandfather, came into the store around 3 am, said they’d found the man who killed my grandfather hidden in a backwoods shack, and that – here’s #2 – a lynch mob had been formed, but had dispersed because they couldn’t find a white man to lead them.

And #3) The killer turned out to be the boy my grandfather had adopted 19 years earlier.

Margaret: Unbelievable.

Bernie: There are just a lot of stories like that about the South that defy the stereotypes.

Margaret: So, you’re saying the accusations of racism have been exaggerated?

Bernie: Well, no. I’m just saying it’s complicated. When I got older, I could see that things weren’t exactly as they’d appeared to me as a child. I grew up in my daddy’s grocery store on Bladen Street, and it always seemed to me that the blacks who came in were “better” than the whites. They were well-dressed. They were polite. They loved Daddy. Nobody had any money, black or white, but it was the blacks who always gave me a nickel. It was the whites – they usually came in from Coastal Cabinet Works or were drunks renting rooms behind the store – who were unshaven and dirty; they’d have saltine crackers with sardines on top for breakfast, then chase ‘em down with Blue Ribbon beer. This is what I saw as a boy, so I thought, “This is what whites are like and this is what blacks are like.” I assumed everybody thought that.

And Daddy didn’t have a racist bone in his body; his parents were immigrants. So I thought everybody was like that. But as I got older and went off to school, I realized things weren’t quite what they seemed. I remember when I was 12, one of my friends was talking about a very important public official in town – you’d recognize his name if I told you – and my buddy said, “He’s got him a little n–––– gal out on the island.” I didn’t think much about this at the time. I was 12; a thought would have been about as identifiable as a UFO. But it stayed with me.

And then later, there was this episode: A friend walks into Mr. Clark’s 10th grade algebra class one day and he’s late. Mr. Clark says, “How come you’re late?” “I just got in an automobile accident,” says my friend. “I hope nobody was hurt,” says Mr. Clark. “Naw,” says my friend. “Just ran over a n–––––.”

Margaret: Seriously? That was his response?

Bernie: Yep. And I was old enough then – 15 or 16 – that it registered. But this boy, he didn’t think a thing about it. I don’t know if anybody else did, either. You heard the word all the time. So, racism was certainly a part of growing up here. But there were all sorts of prejudices. If anything, I probably had a light prejudice against Catholics, because I didn’t know any until I met Pat (Conroy). I would imagine them in that little church with their incense… imagine bats flying around in there. I remember thinking, “Wow, they’ve probably got Dracula in there.” (Laughs.) Nobody ever talked about my Jewishness. Perched on the shoulder of cordiality was a little bird, and nobody mentioned it. Eventually, I realized the silence was driving me crazy.

That continued when I went off to college. At Newberry, I was pinned to this girl who lived in Charleston, and I adored her. She really liked me, too. She thought I was hilarious. She was not Jewish.

Margaret: Was that a problem?

Bernie: It was not a problem at all. At least I didn’t think so. One day, we’re talking about getting married, having kids, and she says, “How many do you want?” and I say, “How many do you want?” She was really hyper, I remember, and she just kept talking and talking, and at some point she said, “Now, Bernie, you’re a Jew and I’m a Christian and my parents and all… but that’s okay . . .” She just kept insisting it was okay. Turns out it wasn’t okay. Not with her parents. But I didn’t figure that out ‘til much later, because I had no frame of reference for being rejected because I was Jewish. It had never happened. And it wasn’t anti-semitism, either. It was, “What will the children be?” But she didn’t tell me this at the time; she just cut it off soon after that conversation, and I didn’t know why. I kept looking in the mirror thinking, “Maybe I’m ugly.” It took me probably 8-10 years to figure it out, when I was writing a memoir and remembered the conversation. And that taught me a lesson – it’s better to know than not know. Uncertainty is terrible – especially for a Jew. Because we’re OCD.

Margaret: Yeah, there are times in Famous All Over Town when Bert Levy (one of the main characters, a psychiatrist for the military) seems to be driving himself crazy with his obsessiveness. Is there some Bernie Schein in Bert Levy?

Bernie: Absolutely. No question. He’s my alter ego. But Bert’s even crazier than me, thank God!

Margaret: What about the other major Jewish character, Murray Gold? Any Bernie Schein in Murray?

Bernie: Murray Gold is not me – he’s too sane! – but his thoughts on feeling less Jewish because he’s southern . . . those are mine. Also, that whole descriptive section – the town of Somerset seen through his eyes – that’s totally me. That’s how I feel about Beaufort.

Margaret: I thought some of your descriptive passages were absolutely beautiful. Really powerful and lyrical. I think you actually rivaled your friend Pat Conroy in some of those sections.

Bernie: Be sure to tell Pat, after you read his next book, that it was good… but it wasn’t quite Bernie. (laughs)

Margaret: Ha! Speaking of Pat Conroy, he’s the only “real person” who appears in your book. He has a small cameo as a high school teacher who goes on to become a famous writer. All the other characters are fictional, albeit many are “loosely based” on people you’ve known. Why did you include Pat as himself?

Bernie: Well, some people don’t know what a great teacher Pat was. I mean, they do, but they don’t know just how great. We taught a creative writing course together in Atlanta, and he was just spectacular. And he really fought for those kids. So, in the book, I wanted to pay tribute to him – as a teacher, and as a good man.

Pat had a big influence on this book. When we were teaching together in Atlanta, he opened up the whole world of abuse to me. He used to talk about it when we were younger – about his father – and I thought he was exaggerating, being over-dramatic. But what I didn’t know back then is that when you’ve been abused like that, there are two things you can become: either the world’s biggest liar, or – if you’re Pat, with that great sensitivity and great sense of joy – you become a great truth teller, through fiction. And he has. And he tells the truth more than anybody I know in a very profound way. It wasn’t until Pat gave me The Great Santini manuscript to read that I realized everything he’d told me about his dad was true. I went to his house and apologized. “I’m sorry. I didn’t know.” I asked him to come speak to a few of my students who I suspected had been abused, and he was great. Just great. I learned so much.

So I think Pat was a huge influence on the therapy sessions in the book between Bert Levy and Jack McGowan (the Marine character based on Matthew McKeon of the notorious Ribbon Creek incident). Hearing the stories of my students at Paideia, and Pat’s story, did the same thing for me as an adult that hearing the comment about “the little n––––– girl out on the island” did for me as a kid. It opened my eyes. Made me realize that things weren’t what they appeared to be, that people had secrets.

Margaret: Is that why you wrote the book? To take a closer look beneath the surface?

Bernie: I think so. Look, I’m a Jewish Southerner. So I’m an anomaly as a Jew and as a Southerner. I’m different, marginal. Once I realized that, I began to see other people more clearly, began to see that we’re all marginal in some way. Because nobody is 100 percent true to themselves. You can’t be. Once you have to hide something about yourself, you have marginalized yourself.

So, after I was able to write about myself, all these characters began speaking to me in my imagination. Gays coming out, a war criminal, a war hero who’s a transvestite, the sheriff with his black mistress, the preacher’s daughter who was sexually abused, the preacher himself, the fallen southern belle. They all started talking to me.

Margaret: So, just how autobiographical is Famous All Over Town, anyway? Will people here in Beaufort recognize themselves in its pages?

Bernie: The book is inspired by Beaufort and by people I have known. But it’s a work of fiction, a child of my imagination. Will people see themselves the book? Or parts of themselves? Of course they will. Will they see Beaufort? Absolutely. But will somebody in Ludowici, GA see the same people and the same things? Yeah.

This is intimate, small town stuff. In a small town, everybody knows everybody else; but what we don’t know about each other is profound. In the end, as it turns out, we’re all insiders and we’re all outsiders.

Bernie Schein is a lifelong educator, a published author, and a Beaufort native. Famous All Over Town (Story River Books) is his first novel. Readers can visit him online at www.bernieschein.com or pose questions and comments by calling the Bernie Schein Hotline at 843-321-9848.

Margaret Evans is the editor of Lowcountry Weekly. She writes a regular column Rants & Raves and blogs at www.memargaret.com