Conversations from the Virtual Porch of the Pat Conroy Literary Center

Conversations from the Virtual Porch of the Pat Conroy Literary Center

Editor’s Note: Pat Conroy did lots of talking – and plenty of writing, too – on the porch of his home overlooking Battery Creek. Now, the Pat Conroy Literary Center has launched “Porch Talk,” a series of free-wheeling conversations between writers from Beaufort and beyond. Lowcountry Weekly will regularly feature excerpts of those conversations, starting with this one between novelist/porch “hostess” Janis Owens and novelist/poet Ellen Malphrus. Consider this your invitation to eavesdrop on The Porch.

Janice Owens: Welcome our friend and Lowcountry neighbor to the Porch: poet, teacher, and novelist Ellen Malphrus. The last I saw Ellen was at the sad occasion of Pat’s last days, where she and her husband Andy not only provided emotional support and loving presence, but an unending supply of succulent Peruvian chicken from Andy’s forthcoming restaurant in Bluffton. As any southerner will tell you, the woman who brings the best food to a crisis is a Woman To Remember.

Ellen, let me say that I am powerfully impressed with the scope of your work. You are a triple threat: a poet, creative writing professor at USCB, and lately a novelist with a critically acclaimed book, Untying the Moon.

Speaking on behalf of lazy writers everywhere, I have to ask: where do you find the time? What does a working day in your life look like?

Ellen Malphrus: It seems to me that the key phrase of your question is “in your life” because there is life, after all, and if you aren’t engaged in it, what is there to write about? Right, Janis? Or is that just the rationalization of yet another lazy writer?

Like most of us, I spend a lot of time lamenting the lack of hours in the day. When I’m not whining, when I’m focused and on my game, my writing day begins in the wee hours as visitants arrive from the hinterlands of dreamscapes—those lush places where all is possible. I drift into wakefulness as slowly as I can, transcribing as much as possible before full consciousness kicks in. When it does, I walk across the yard to my writing room, pick up my pen, and set straight into wakeful work before distractions latch hold of me. (In Montana the entire c abin is only one room, so it’s a different deal, but there are also far fewer interruptions.)

abin is only one room, so it’s a different deal, but there are also far fewer interruptions.)

I ride each wave—whether it’s a passage or a paragraph or a sentence or a word—as far as I can, and when it peters out I stand up, step onto the porch, stretch, breathe, maybe light a candle, and catch the next wave. If one doesn’t come along I read for a while or turn to revisions or research. If school isn’t in session I work until lunch time, take a quick break and get back to it. I’m highly susceptible to disruptions, so the trick is to avoid them as long as possible before I harness up the yoke of the harried world around us.

During the semester, I can only write until mid-morning, then move on to the correspondence, class prep, committee chores, student papers, and teapot tempests that are the components of my university work. When I’m really on my game the muses stick with me during the day, though, and I jot down phrases for a poem-in-progress or notes for the novel. I usually keep a notebook nearby to record these gifts, but many of them are scribbled randomly, no doubt entombed under reams of unorganized paperwork stacked on one of my five desks.

The truth is that often I’m not fully on my game. Too many mornings the distractions catch me before I can flee them. But what a wonderful world it is when I don’t get caught. Those are the days when I’m most alive. Those are the days that are golden.

JO: You are a living, working survivor of James Dickey’s poetry workshops at USC (as I am of Harry Crews’ at UF). Dickey was, in fact, your mentor, and you lived to tell the tale. There are so many Dickey experiences; what was yours?

EM: I witnessed various facets of Jim Dickey’s world in the seven years that I was under his wing. I know the tales, and I knew the profoundly complex man behind the persona. Yes, like Harry Crews, Dickey was often larger than life, but because he reminded me of my own imposing father, I was never intimidated by that “largeness.”

Dickey taught me about writing and humanity, and that you can’t be fully engaged in a life of the mind unless you also get your hands dirty. He taught me in the classroom and during our walks through the Horseshoe (on the USC campus), during visits at his home or mine, in conversations under a canopy of trees. He insisted that a writer have guts enough to dance with the dark side that’s part of all our makeup—to explore those nether regions of self and that we suppress at Sunday School and Junior League.

As you know, Pat was also a Dickey student for a while. When he and I became friends, in Maine of all places, we immediately began singing the praises of Big Jim Dickey’s poetry, and we never really shut up. Pat called me his “sister-in-Dickey,” and I like that. A lot. Dickey used to tell me, “Now when I’m gone from here, you listen out for me over the celestial wireless.” I have listened, and I have heard, just as I’ve continued to hear Pat. And girl, I’m sure the two of them are having a fine ol’ time, chewing the literary fat out there in the great beyond.

JO: Our friend Pat Conroy was a fount of good advice for other writers, especially first time novelists. Care to share the piece of advice that you found most helpful (or hilarious. Or both?).

EM: Pat’s most oft repeated advice to me was that simplest, most obvious, yet often most difficult to carry out decree of all time. It was inevitably preceded by dictates and threats such as, “Malphrus, you don’t need to be flitting off to Spain. You need to sit your ass at your desk and get your work done.” Or, “Malphrus, I’m gonna drive to Bluffton and break that damned banjo. You don’t need bluegrass, you need to sit your ass at your desk and get your work done.”

He also counseled by example. His final “well” words to me were, “Malphrus, I’m a trooper.” That’s what he said when he got in the car to drive home from E. Shaver’s in Savannah, from what would be the final book signing of his life. He said this in response to my thanks for his being there and my concern that he’d been feeling a bit poorly and was over doing it. It won’t surprise you, dear Janis, that Pat Conroy’s last book event wasn’t spent autographing his own books. He was there signing the foreword he’d written for mine. Generosity. And never mind about feeling poorly. He had said he’d be there, and by god that’s all there was to it for a trooper named Conroy. Think of how many of us were offered his example of boundless generosity and unrelenting commitment.

I might also mention a practical piece of advice Pat gave me the day of my book launch last October. He was at my side, again signing the foreword to my novel Untying the Moon. When the first reader approached, Pat leaned over to me with one of those twinkling blue-eyed smiles and said, “You’ve got this, kid. Just remember, don’t ever sign a book before the reader spells his name. I don’t care if it’s Bob.” That has proven to be handy advice indeed . . .

To read the rest of this interview, visit www.patconroyliterarycenter.org

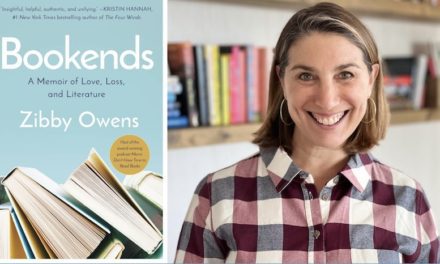

Janis Owens is a novelist, memoirist, folklorist, and storyteller. She lives in Newberry, Florida, and Golden, Colorado, and is working on her fifth novel.