America’s First “Truck”

America’s First “Truck”

If you saw the 16th century Spanish ship in April you experienced a real treat. The replica of the San Pelayo that landed at Port Royal gave us a good idea of how the first European pioneers traveled from Seville to the New World.

The San Pelayo was a galleon, and galleons had up to four decks. When Pedro Menendez de Aviles raced to the colony of La Florida in 1565 he had approximately 476 people on board his flagship, San Pelayo. That included 76 seamen, 18 artillerymen, one ship pilot, 316 soldiers and approximately 65 settlers.

But the San Pelayo was not your everyday working ship that moved settlers and cargo up and down the colony’s coast line. Galleons like the San Pelayo only traveled between ports that had deep harbors. Thus, most of the time Spain’s galleons traveled with cargo, settlers, or returning treasure. They typically sailed between Seville, Spain, and Cartagena (Columbia), Havana, (Cuba), Veracruz (Mexico), and Santa Elena (South Carolina).

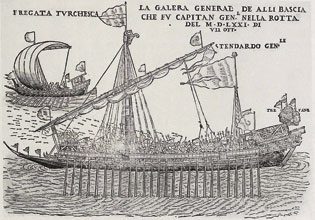

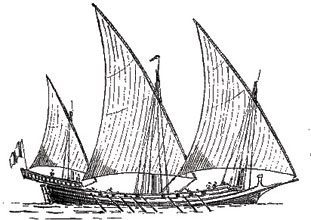

So what was the type of ship that was the “first working ship?” What was the ship that moved people and goods between San Juan, Porto Rico and St. Augustine or between Havana and Santa Elena? What was the “truck” of 1569? That “truck” was the fragata. And you will not believe how it looked. It was designed in the medieval period as a working ship for the Mediterranean. When I first learned that the fragata was the first working ship of our European pioneers I was shocked.

I’d always imagined the typical “first ship” was an English galleon . . . the type that we saw in our early American history books. It was a sailing ship. It certainly was not propelled by oars and sails. But then we must remind ourselves – almost everything we have been taught is about how the English first discovered what is now the United States. And that lesson is dead wrong. The Spanish first settled what is now the United States, not the English.

William C. Fleetwood, Jr. does a great job of describing this working “truck” of 1569 in his book TIDECRAFT. “The Spanish fragata of the period was a small to medium size, armed vessel. It was built for speed and handiness. Rigged for sail and oar, the craft was small enough to easily enter shoal harbors (like St. Augustine), but able to make ocean voyages. The ship was more of an armed scout, much like the larger 18th century frigate.”

However, Spain built a number of large fragata’s in its first colony and one of them was built right here at Santa Elena. Pedro Menendez was authorized to construct eight fragatas in the colony.

The fragata “Santa Elena” was actually built at Santa Elena. This was a large vessel, probably about 85’ to 100’ long compared to the average length of 65’ and beam of 15’. It would have had three masts and used square sails.

It had six large cannon, each weighing from 1,100 to 2,100 pounds. It was propelled by 36 oars. With that size each oar probably had two seamen behind it. The “Santa Elena” made its maiden voyage on August 2, 1572.

What was it like to sail these medieval ships in Port Royal Sound or along our coastline? William Fleetwood helps us answer that question.

“Remember,” he says, “when these ships sailed, and rowed, up and down our coast they had no aluminum, nylon, Dacron, fiberglass, plastic, or rubber in the ships. They had no lights except oil lamps and candles, and no safety equipment but two hands.

“The ship was constructed of wood, iron, bronze, flax, and hemp. It might sail within 45 degrees of the true wind. There were no bunks except for the captain’s, no foul weather gear except the wool clothes on their backs, no sunscreen, sunglasses, toilet paper, or medicines.

“If you were the captain you are aware that there is not a single man-made navigational marker or light anywhere on the coast, and no navigational instruments on board . . . only lead lines, a compass, and an hour glass.”

This is a life that is difficult to imagine. But it was how our first Santa Elena settlers traveled along the coast line. To navigate they could compute latitude, but not longitude. Thus, if a ship’s pilot came within one hundred miles of a destination, he felt successful.

When Spain’s King Philip II asked the Governor of Cuba to dispatch a ship to see if France’s Fort Charlesfort was still operational, the governor sent Captain de Rojas in 1564. Rojas sailed, and rowed, the fragata Nuestra Senora de la Concepcion up St. Helena Sound to the Broad River and then East to Parris Island.

Along the way he found the last Frenchman of Charlesfort. Rojas made this round trip of roughly 1,200 miles in only a month. By any account this was good timing. Pedro Menendez made a similar trip to Spain in 1567 aboard the fragata, “El Aguila” (the eagle).

He made that trip from Santa Elena to the Azores in only 17 days. He averaged a speed over over six knots. To make that crossing Governor Pedro Menendez would have stowed the cannon and anchors below, lashed the oars inside, and raised sails on all three masts.

Living conditions aboard these ships is hard to imagine. Carla Rahn Phillips graphically describes the situation in her book, Spain’s Men of the Sea. The fragata had only one useable deck and most of it was open to the weather. The one inner deck held the ballast, armament, and provisions. The crew and passengers would sleep on the open deck. There was no room in the inner deck.

St. Augustine became the first military garrison in 1565. However, Santa Elena was the first major European settlement in 1569. St. Augustine was not a real settlement until after 1580. If you had a compelling reason to return to Spain in 1569, you might have hitched a ride on one of the Treasure Fleet’s returning galleons. To make that trip, Carla Rahn Phillips tells us what you would have had to eat . . . and how the table would have been set.

- For Mondays, Wednesday, Fridays, and Saturdays a pound and a half of biscuits, one liter of water, one liter of wine, and half a peck of horse beans mixed with chickpeas would be divided among 12 people. One pound of fish would be rationed to every three people. Don’t think of the “biscuits” that they ate as anything close to what we enjoy today.

The 16th century ship biscuit was a twice baked piece of unleavened bread. The double cooking preserved it from deteriorating at sea. When the crew was rationed a biscuit they had to soak it in either water or wine to make it eatable. Most chose wine.

- On Thursday and Sunday you would eat meat instead of fish and two ounces of cheese.

- The fish and meat were always salted and served with wine or water as a stew.

- Typically only the ship’s pilot and master ate at a table with chairs. If you were a high ranking official you would have joined them. However, if you were a commoner, or one of the ship’s crew, you would have eaten food that you placed on your sea chest. There were no chairs for the crew. You would have eaten from a wooden or clay platter using the knife you took from your belt.

If you were traveling to, say Havana, on a fragata, you had to search for a place to sleep. When it was bed time, the crew would seek out a level place on the decks, which was not always easy. Then they would extend their sleeping pads, which in many cases were simple sacks filled with straw and covered with a blanket. There was no fixed place to sleep. If during the night the position of the sails had to be changed and a sailor had found a place to sleep under the sail, the unhappy sleeper was awakened and told to move.

There were no toilets on board these ships. If a sailor needed to go to the bathroom, he would go to a wooden grating that projected over the prow (or front) of the ship. The officers and rich passengers would go to the grating that extended over the poop deck . . . or back of the ship.

To me there is a real message in learning about these extreme hardships of our first European settlers, and it is this: America was not an overnight success. It took hundreds of thousands of early settlers to risk their lives and to endure incredible trials.

First, they had to go through the insecurity of deciding to move to an unknown land. Then, they had to face unimaginable hardships just to get there. They faced danger at every turn . . . a lack of food, disease, and unknown enemies. However, most of them had a deep faith.

Today they remind us of those values which we must fight for to stay strong: a willingness to change; a willingness to take risks; a willingness to never give up when we face repeated difficulties; and a strong belief in God. And they remind us that opportunity and freedom are never free.

The next time my granddaughter travels with us and says, “Are we there yet?” I have a real story to tell her.