A southern lit fan meets one of his heroes, thanks to USCB’s Lunch with Author Series.

A southern lit fan meets one of his heroes, thanks to USCB’s Lunch with Author Series.

It was my wife who alerted me to the press release regarding author Ron Rash’s visit to Hilton Head as part of USCB’s “Lunch With Author” series. It was an early birthday gift that she even told me about it, much less that she agreed to go with me.

I could, and do, go on incessantly about the importance of not only the preservation but continual creation of authentic Southern literature. I do this in my own home, mostly, because my long-suffering wife has nowhere to run and our marriage included a contract stating that she at least pretend to listen faithfully to my droning.

She should be used to it – as fellow students in Shirley Tuttle’s English and Journalism classes at Beaufort High sometime last century, we were both introduced to the power of published words. Mrs. Tuttle should be proud of the foundation she set. Several of her former students and my former classmates (from little old Beaufort) have gone on to major in Journalism and English at schools in South Carolina, Illinois, and Missouri. At the very least, she taught us to think critically and open-mindedly, such as when my complaints about the works of Joan Didion and Herman Melville were met with a succinct “suck it up and read them anyway, you might learn something.”

My earnest devotion, however, began during a Southern Literature class at Clemson, where my professor brought to life the wonder of southern works of fiction by peppering his lectures with anecdotes about the authors, many of whom he knew personally. It’s one thing to listen to a discussion about gothic prevalence in works by O’Connor or Faulkner. It’s quite another to hear your professor say, “and when I was drinking with Truman Capote in the late 70’s, he told me….”

So I ate it up – that delicious bit of Lee Smith and Ernest Gaines and Carson McCullers and Harper Lee that is common to those of us native to the south. The settings and the people, whether the bayous of Louisiana or the courtrooms of Alabama, were familiar and comfortable. As another titan, Eudora Welty, said, “one place better understood helps us understand all other places better.”

It was after getting my feet wet with those foundational authors that I discovered, almost by  accident, the two who would become my favorites to read. The first is Walker Percy, who wrote The Moviegoer in 1961 with me in mind, at least I think. I read a few chapters and realized that Percy was writing about the existential angst I had also long felt. After I read his other novels, I became somewhat convinced that despite my previous non-belief in and non-practice of Buddhism, I must somehow be Walker Percy reincarnated. The fact that I was 11 years old when he died and our life spans obviously overlapped has not yet been factored into my thinking.

accident, the two who would become my favorites to read. The first is Walker Percy, who wrote The Moviegoer in 1961 with me in mind, at least I think. I read a few chapters and realized that Percy was writing about the existential angst I had also long felt. After I read his other novels, I became somewhat convinced that despite my previous non-belief in and non-practice of Buddhism, I must somehow be Walker Percy reincarnated. The fact that I was 11 years old when he died and our life spans obviously overlapped has not yet been factored into my thinking.

But the second author I found who spoke to me was Ron Rash, and I wasn’t going to let an opportunity to hear him get away, even though he lives relatively close by in North Carolina. Rash is the embodiment of the Southern author, the person who writes about what he knows best and sticks to characters and themes that are real and relatable. His contributions to the genre – whether through his poetry, his collections of short stories, or his novels – have ensured that a way of life, specifically that of those who call the Appalachians home, will be preserved for those who love good fiction.

“It takes a lie to point out the truth,” he said of good fiction writing.

His “lies” are all set in western North Carolina and upstate South Carolina. He traces his family’s roots there to the 18th century, and is as ingrained with that area’s culture as Baptists are with prayer meetings. If you’ve never had the chance to spend time in the upstate of South Carolina, or western North Carolina, or eastern Tennessee, or northeast Georgia areas, I suggest you quit reading and head there now.

I found it ironic, but not altogether strange, that Rash was vacationing at the beach on Hilton Head, as those who primarily live in the mountain areas head towards the ocean for respite, while those of us living with salt water lungs head for fresh mountain air at every opportunity. And maybe it’s because I spent significant time in that area as a college student, maybe it’s because I had relatives from that area who spoke the same colloquial languages, or maybe it’s just because Rash is a poetic writer with plots that move swiftly and a master’s command of the language, but his works speak to me as loudly as Percy’s.

The first thing I think about when I read Rash’s work is his acute sense of place. None of his novels are set in the present-day, so it’s also clear that he’s trying to archive and freeze-frame a particular image of Appalachian people in various parts of history. It’s as important as anything a movie about silent films will do.

Land is an important character in all of Rash’s works, and none more so than in the titular cove of his most recent novel, The Cove. It’s as ominous a presence as the rapids in Saints At The River or the farm fields in One Foot In Eden. It’s as identifiable as Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha County and the arid deserts of Cormac McCarthy. History is another subject blended into his novels, whether it’s uncovering the uneasy German presence in North Carolina during World War I, or the forgotten skirmishes in the hills and laurels between native Unionists and native Confederates during the Civil War.

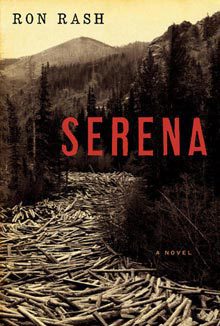

It also struck me, as I glanced at my lunch companions, that I was one of only a handful of men in the audience, and certainly the only one under the age of retirement. It might account for the menu of chicken salad and sponge cake, neither of which came close to fulfilling my daily requirements of meat and more meat. However, it did possibly speak to the tradition among southern authors of creating strong, memorable female characters that Rash continues in his most acclaimed novel, Serena.

Society in the South is still very much a matriarchal one, centered on the woman as the driving force behind any family, whether they work full-time at home or in an office. Serena might be the one novel that showcases an antagonist, but equally strong (if not quite as memorable) are the female protagonists in his other works, including Laurel Shelton in The Cove. She’s as appealing a character, and perhaps as enduring, as a young Scout Finch or an aging Miss Jane Pittman.

And that’s the essence of Rash. He’s not writing anything new. He’s writing about the familiar, capturing the best and worst of humanity in a region of the South that deserves as much attention as its more glamorous counterparts in Nashville, Atlanta and New Orleans. He takes care in selecting his words, and rather than appealing to a lowest common denominator among potential readers, he contributes to our understanding of time and place in this world. It’s why he will eventually be studied in college literature classes.

In the South, we are not that far removed from our agrarian roots. My grandparents all grew up on working farms in various parts of South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. Be it livestock, timber or tobacco, that way of life is not too far gone to be erased completely from our memories, even if our memories are only stories and imaginings handed down by older generations. Thank goodness Rash chose to take the images and memories from his head and put them to paper.

Fittingly, when my turn in line came and I approached Rash for an autograph after his speech, I didn’t bring along my Kindle to try for an awkward, electronic signature. Some authors, and some subjects, are still worth a good old hardcover.