Everybody has their Tales from the Time of Coronavirus, and thanks to social media, those tales are being widely and wonderfully told. From the harrowing to the humorous to the merely mundane, we’re all telling our stories, because here in the land of humans, stories save. They always have and they always will. Hallelujah!

We have a specific story unfolding at our house, and it’s one you might not have heard. Our 18-year-old daughter was a Rotary Youth Exchange Student living in the Czech Republic when the pandemic forced us to bring her home in late March, three months early. It was a decision nobody made lightly – neither Amelia nor her parents – but when the US State Department announced that American citizens should come home ASAP or prepare to “shelter in place for the duration of the pandemic,” the decision became much easier. The best parts of Amelia’s exchange – the promise of European travel and springtime fun with friends that had buoyed her spirits through the cold, dark Czech winter – were disintegrating before her eyes, and we all decided she would be happier and more comfortable “sheltering in place” in her own home. Especially since nobody knew when “the duration” would end.

Foreign exchange is always an emotional roller coaster, and it tends to take a similar track for most students. They arrive in their host countries, have an initial “honeymoon phase,” then sink into irritability and confusion before rising again, gradually adapting toward feelings of contentment, proficiency and cultural integration. This whole process plays out over a span of 10-12 months. In our daughter’s case, she was yanked off the track after seven months, just when her roller coaster car was on the steep incline. Though she could finally see it, she never got to reach the top. She never got to experience those coveted feelings of mastery and ease, that sense of truly belonging to another culture. Because of quarantine, she didn’t even get to say a proper goodbye to her fellow Rotary exchange students, the friends she’d bonded with and grown to love. Instead, they gathered beneath her window on a cold, dreary day – Diego from Brazil, Agus from Argentina, Victor from Canada, and Cecilia from Bolivia – and stood waving up at her with masks on their faces and tears in their eyes.

Amelia texted me a photo of that scene, and there are tears in my eyes just thinking about it now. This is the week Jeff and I had planned our big trip to visit her in Ostrava, after first touring Prague. I was so looking forward to meeting those kids in person and taking them out to dinner.

When they return to their home countries, exchange students almost always experience something called “reverse culture shock.” Some say it’s even harder than the culture shock they experience upon arriving in their host countries. There’s an initial excitement at coming home, but also sadness at leaving their host country and frustration at how “different” home now feels. This is the norm.

For exchange students like my daughter – and there are plenty of them out there right now – there is no norm, no chart or graph of emotional milestones they can expect to hit. Having had their exchanges cut short abruptly, just when they were beginning to thrive, they have all the “reverse culture shock” stuff to deal with, but there are lots of other emotions, too, including feelings of disappointment, anger, confusion, and even failure. To top it off, thanks to social distancing, they’ve come home to a very different world than the one they left. There are no welcome parties, no joyful reunions with old friends, no fanfare or excitement. It’s grim.

It’s hard to watch your child struggle through something for which there is no guidebook, something that looks a lot like grief. When I think of all the years Amelia dreamed of being an exchange student – and the full year she spent applying, training, and preparing to realize that dream – I feel her loss as if it were a strange kind of death.

A First World Problem? Definitely. A small sorrow in a world of enormous grief? Absolutely. But this is our story. It’s not the most important story, not even close, but it’s the one we have to tell.

When she tells it herself, years from now – with the clarity of hindsight – Amelia’s “exchange story” will almost certainly be a happy one, a memory perhaps even more precious, more dearly held, because of its poignant, dramatic ending. But for now, we are still too close to the thing.

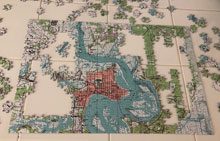

Since she got home, over two weeks ago, Amelia and I have been working a jigsaw puzzle together. No, not jigsaw puzzles… a jigsaw puzzle. It’s one my husband ordered for Christmas when she was just a little girl. She wasn’t interested back then, and that’s probably a good thing, because it’s ridiculously hard! Custom-made by National Geographic, the puzzle is a map of Beaufort and the surrounding area, featuring our home neighborhood – Pigeon Point – in the center.

Since she got home, over two weeks ago, Amelia and I have been working a jigsaw puzzle together. No, not jigsaw puzzles… a jigsaw puzzle. It’s one my husband ordered for Christmas when she was just a little girl. She wasn’t interested back then, and that’s probably a good thing, because it’s ridiculously hard! Custom-made by National Geographic, the puzzle is a map of Beaufort and the surrounding area, featuring our home neighborhood – Pigeon Point – in the center.

The pieces are very small and hard to distinguish one from another. Since the puzzle is over a decade old, many of the places depicted there no longer exist, or their names have changed, so the words on the map are often more misleading than helpful. The biggest challenge, though, is that there is no picture on the box showing us how the completed puzzle should look. We’re kind of flying blind.

But we’re relishing our time at the puzzle table. The quiet talks. The silly laughter. The problem solving. The story telling. Working puzzles together is something we never, ever did before Amelia traveled abroad – before she discovered the width of the world and the depths of herself. It’s something completely new for us.

And it’s very difficult. But day by day, piece by piece, an image of home is emerging. It’s not exactly the home we thought we knew, and we’re not quite sure what it will look like, but we’re getting there.