Suddenly, all the newspapers – and even big billboards on the highway – are telling us that “Santa Elena came before Jamestown,” or, as Dr. Larry Rowland puts it, “This is where America began!” But how is this possible? Before last year, had anybody even heard of Santa Elena? Our teachers never covered this chapter of American history.

Suddenly, all the newspapers – and even big billboards on the highway – are telling us that “Santa Elena came before Jamestown,” or, as Dr. Larry Rowland puts it, “This is where America began!” But how is this possible? Before last year, had anybody even heard of Santa Elena? Our teachers never covered this chapter of American history.

So how did this story come to light?

When new history is discovered it must go through a series of steps before it is accepted. Usually, one or more specialized historians, or archaeologists, will make what they believe is a profound discovery. Then, they present their findings to a group of peers. If these peers accept the findings, academic papers are usually presented to a wider group of historians. Then, if those historians believe the discovery is profound, and that it broadens our understanding, book publishers will revise their textbooks. This process is accelerated if the historical discovery is contrary to what we already know . . . or if it has the potential to impact a lot of people. The discovery of Santa Elena is taking this route. As it turns out, the story behind Santa Elena is shocking in light of what we’ve all been taught and monumental in its potential impact on all Americans.

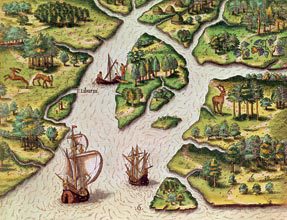

When France’s Jean Ribault landed at Parris Island in 1562 he stayed long enough to help the thirty intended settlers build Charlesfort. His plan was to then depart for France, collect back-up provisions, and return to Charlesfort within six months. It didn’t happen. When he returned to Dieppe, France, his allied Huguenots were fighting a raging religious war with the Catholic government at Dieppe. Looking for an alternative, Ribault went to England and tried to encourage Queen Elizabeth to loan him the supplies and vessels that he needed. It didn’t work. Before long he was imprisoned in London Tower for trying to secretly obtain English vessels for France. While Jean Ribault was in prison he wrote a fascinating story of his voyage to Charlesfort. That book, The Whole and True Discovery of Terra Florida, became a best seller in England and Europe. Moreover, the book found itself in the trunks of the first English settlers who landed in Beaufort County in the 1670s. According to Dr. Rowland, these English settlers came from Barbados. With the help of this book, some of those early residents found the general area where they believed Charlesfort existed. Before long it had become a popular Sunday afternoon outing. People would go to Parris Island and look for pottery shards.

The Marine Corps, knowing the value of the historic site, sent Major George  Osterhout – who had done some previous amateur archeology in Haiti – to examine the location. He published his findings in 1924, claiming Parris Island was the site of a French fort.

Osterhout – who had done some previous amateur archeology in Haiti – to examine the location. He published his findings in 1924, claiming Parris Island was the site of a French fort.

Around that time, Florida was becoming the academic seed bed for 16th century historians. (At best South Carolina had only one 16th century Colonial historian from 1930-1960 – Alexander Salley, Jr. ) In 1925, Florida’s historian Jeannette Connor challenged Osterhaut’s findings, stating, “I believe that the Spanish capital of La Florida is on Parris Island.” But where had she found her clues? By the mid-1920s, historians had started to translate Spain’s 16th century documents for the first time, driven by a general interest among California historians to uncover the background of their Spanish missions. Our Southeastern U.S. historians were fascinated by this new source of history. Thus, when Major Osterhout published his first report on Charlesfort in 1924, historians such as Ms. Connor mused: Maybe a translation of these 16th century documents would help us locate Santa Elena.

Remember the significance of La Florida? By 1540, Spain’s King Charles V claimed all territory from Newfoundland to the Keys and from the Atlantic Ocean to at least the Mississippi River. So, ”La Florida” was not the state of Florida. It was half of what became the “lower 48” states.

After Ms. Connor made her challenge, others followed. Now there was a small group of 16th century historians who basically said, “The Parris Island 16th century fort is Spanish, stupid.” But their challenge was based on a review of Spanish documents . . . not evidence of Spanish artifacts. Their message did not get any traction. The group that did get some traction was the South Carolina Huguenot Society. They got the Federal government to erect a monument on the Parris Island site in 1926 that reads, “This is France’s Charlesfort.” This is a mistake. If you go to the Charlesfort-Santa Elena site on Parris Island today, you will see a large federally-funded monument that says, “This is the site of France’s Charlesfort.” It is not! It is the site of Spain’s Fort Marcos I (1577-1582).

Next issue: Conclusion of How Santa Elena was discovered.

My thanks to three of the nation’s most important historians for their input to this story: Dr. Eugene Lyon, Dr. Paul Hoffman, and Dr. Chester DePratter. Each of them is a member of the Santa Elena Foundation’s Board of Advisors.