An interview with film composer Charles Denler, recipient of BIFF’s Jean Ribaut Award

A rising star in the rarified world of making music for the movies receives the Jean Ribaut Award for Excellence in Music for Film

Charles Denler has a lot on his plate. According to Film Music Magazine, Denler holds the record for having more upcoming films than any other composer in the business to date. His resume includes the music for more than a hundred feature films, documentaries and television programs including the theme for Oprah. He’s picked up a trophy case full of medals and awards along the way, including a pair of Emmys.

Denler trained at the Berklee School of Music in Boston and went on to record a number of critically acclaimed albums before making the transition to his current career path. We spoke by phone from his home studio in the snowbound outskirts of Denver. He was looking forward to traveling with his wife to Beaufort, a place with some sentimental history for the couple.

Charles Denler: We honeymooned there almost twenty years ago out on Fripp Island and frequented Beaufort. It’s kind of fun to head back there and Ron [Tucker] is good people, so we’re really looking forward to it.

Mark Shaffer: Things have changed a bit in twenty years.

CD: (Laughs) Really?

MS: Just a bit. I know you’re excited to receive the Ribaut Award and BIFF is a bit more low key than some of the festivals you’re used to attending. Does that make it more appealing?

CD: Actually, that’s something I look forward to – a more intimate venue. The problem at Sundance and other places is that you never really get to hang out with anybody. I love the more relaxed atmosphere [of BIFF] and hopefully I’ll be able to build some new relationships, make some new friends and that’s one of the things I love about the smaller festival circuit.

MS: How did you begin composing for television and film?

CD: I’d worked with churches for years as a minister of music and I’d started writing cantatas and working with big choirs and orchestras and people would often say that my music sounded theatrical. Years later a couple of producers from National Geographic got a hold of one of my albums and asked me to write music for their documentaries.

MS: What sort of projects are you working on now?

CD: There are quite a few things. I’m finishing an animated film with Richard Gere that’s a wonderful film about baseball, Henry and Me. Cindy Lauper sings one of the songs and she’s also one of the voices with Richard. The soundtrack premiers with the Colorado Symphony Orchestra live in October and we’re working to have Cindy there to sing with us. I just finished up a fun little film called Lab Rats with some filmmakers in England. What else…

MS: We’ll just take Film Music Magazine at its word that you’re a busy guy.

CD: Most of those projects have yet to go into production, but there’s a lot out there.

MS: I’m a huge fan of film scores and composers. Who are your influences or do you draw more from your own experience as a musician and composer?

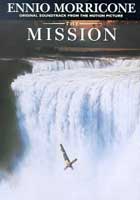

![]() CD: Well it’s certainly a little bit of both. My mentor once told me, “Good composers are completely original but great composers copy great composers.” I try to spend some time every day studying great composers – Beethoven, Brahms, a lot of Bach. But then I also study contemporary composers like Ennio Morricone –

CD: Well it’s certainly a little bit of both. My mentor once told me, “Good composers are completely original but great composers copy great composers.” I try to spend some time every day studying great composers – Beethoven, Brahms, a lot of Bach. But then I also study contemporary composers like Ennio Morricone –

MS: Ah, The Maestro.

CD: His score for The Mission is probably one of my all time favorites and the reason I am film scoring. I remember seeing The Mission back in the ‘80’s and something snapped in me. It took a few years to surface, but when I heard that music it just stirred my soul. Definitely Morricone and – of course – John Williams. I listen to a ton of John Williams. He’s the most lyrical composer in history. His music is amazing. I don’t know if we’ll ever see those days again where the themes [in film] are so brilliant.

MS: I agree and this is strange: just before we began this conversation, I posted a preview of this  interview on our film blog after listening to some of your work and I actually mentioned Morricone and Williams.

interview on our film blog after listening to some of your work and I actually mentioned Morricone and Williams.

CD: Wow, (laughs) that’s funny.

MS: Incidentally, they’re two of my favorites. Their stuff is incredibly iconic.

CD: It is. It’s lyrical and thematic. You know, I’ve told my agent and my friends and producers and directors I work with that if you want “sound effect music” don’t call me. I won’t do it. I refuse to do it. I believe that there’s still a place for melody in film – something that’s not part of the sound effects library they’re using to sweeten the film, but something that actually gives the film a signature sound. There are still a few films out there that do that and a few directors who look for a signature theme for their film.

MS: Who’s out there that you’d like to work with these days?

CD: Steven Spielberg, M. Night Shayamalan – directors whose films actually have themes in the music.

MS: As far as Spielberg is concerned, I can’t think of a filmmaker over the last 30 years or more who’s contributed more to that thematic lexicon – all of it with John Williams. The themes are central, they’re practically characters.

CD: Yeah. Peter Jackson’s like that, too with what he did with Howard Shore in The Lord of the Rings. The music is literally a narrative throughout the films – another voice that’s telling you how to feel. It’s remarkable how a good director knows that. I’m not saying the others are bad directors by any means, I’m just saying that a good director knows that the music is meant to be a narrator. It’s there to tell the audience they’re feeling sad, they’re feeling happy or triumphant. That narrator is weaving this voice throughout the film and audiences respond to that.

CD: Yeah. Peter Jackson’s like that, too with what he did with Howard Shore in The Lord of the Rings. The music is literally a narrative throughout the films – another voice that’s telling you how to feel. It’s remarkable how a good director knows that. I’m not saying the others are bad directors by any means, I’m just saying that a good director knows that the music is meant to be a narrator. It’s there to tell the audience they’re feeling sad, they’re feeling happy or triumphant. That narrator is weaving this voice throughout the film and audiences respond to that.

It won’t be long before audiences start saying, “Hey, all this music sounds the same. Is there any chance we could get somebody to actually write some music for this film?” I’m holding out for that. I carry that banner.

MS: I think you’re in this class of younger guys who’ve taken – no pun intended – notes from the seniors. Michael Giacchino (The Incredibles, Star Trek), David Arnold (Casino Royale), David Holmes (Ocean’s 11,12,13) are in there, to name a few.

Let’s break down the process. Where does a score begin for you?

CD: It usually begins with the screenplay. That’s an important part of the process for me. I’ll start to hear the music as I’m reading the script.

MS: Really?

CD: Yeah. More so because often when I get the rough cut of a film there’s a [temporary score] with it which they use to sort of tell me where they want to go emotionally. But it’s always better for me to have an idea of what the theme is going to be before I hear someone else’s music. So I read the screenplay and the melodies begin to flow in my head. Then I sit down with the rough cut and the director and he gives me notes on the emotion and style he’s looking for. Then I start scoring and usually what happens is that I write the music as a temporary score, electronically with some light instruments and then we take it to an orchestra and record each cue individually.

MS: And you conduct, as well?

CD: Yes.

MS: This is an intricate process I don’t think a lot of people understand.

CD: It’s involved. A lot of people think I just sit there and watch the film once and write the music and kind of place it in there. But the music is written very specifically to each cue. It moves with dialogue, it moves with picture, it lives and breathes within the realm of that film. Then when you’re sitting there live with the orchestra you have to preserve this. When you’re conducting the rhythms are changing, the tempos are changing because in the back of your mind you know this is going to hit at a certain scene – a car crash or a wonderful moment. The music has to flow and breathe with the film. It’s not like getting up and conducting a concert.

MS: In essence, you are directing the music.

CD: Literally. You’re making it speed up, slow down, build in tempo and feeling. It is complicated. It’s a real breather when you’re able to get up and conduct a Beethoven piece that stays in the same tempo for ten minutes. With a film you’re just pulling your hair out. It’s crazy.

MS: Off the top of your head, give me five scores you simply can’t live without.

CD: The first is definitely The Mission. Next would be Jurassic Park.

MS: Really?

CD: I think that might be John Williams strongest work ever. The music is so majestic it’s just amazing. And, yeah, it’s all about these dinosaurs crunching down on people, but the melodies are amazing. Williams’ score for E.T. is next and then Rachel Portman’s score to Chocolate is fantastic. Let’s see, one more. You know, one that’s always touched me is A River Runs Through It. Mark Isham. It’s very simple. In fact, it’s so simple it would probably be rejected today. But there’s something so beautiful about sticking a small ensemble in a room and getting these simple lyrical melodies. That’s probably my top five.

MS: Have you seen anything recently that really caught your attention?

CD: Inception was interesting, but the one that’s stuck with me most this year is How to Train Your Dragon.

MS: John Powell. He’s up for an Oscar for that one. I’ve been a bit mesmerized with what Carter Burwell did for the Coens on True Grit, taking those old hymns and working a thematic landscape around them. Very bare bones.

CD: I appreciate that a lot, the minimalist approach. Carter also did those vampire movies my daughter loves…

MS: The Twilight series.

CD: Right. I couldn’t do those. But my daughter and my wife love them.

MS: We remain blissfully unexposed. This has been great. We look forward to seeing you in person.

CD: It’s going to be fun. I can’t wait to get out there. And to be honest, I could really use the break.

For more about Charles David Denler visit www.charlesdenler.com.