Beaufort’s Reconstruction Initiative Enters Next Phase with the Launch of Educational Programs

Beaufort’s Reconstruction Initiative Enters Next Phase with the Launch of Educational Programs

By Mindy Lucas

Middle school teacher Emily Fowler sat in what amounted to a classroom of her own at the Santa Elena History Center in Beaufort recently.

Fowler, who teaches at Lowcountry Montessori in Beaufort, joined about 15 other educators, volunteers and community leaders for the launch of a new “Teaching the Teachers” pilot program which aims to equip educators with the skills and resources needed to teach Reconstruction.

It’s a period in history that many Americans have no idea even existed, some in the group pointed out.

“I’m really encouraged,” said Fowler later on a break, discussing the training.

Once a history major herself, Fowler said it’s the Montessori philosophy, or “Pedagogical Place,” to give students a sense of where they fit into the timeline of history.

“I think this training will fit in well with that (philosophy),” she said.

The pilot program is actually one of several educational initiatives recently launched by the same group that successfully pushed for the designation of Beaufort’s Reconstruction Era National Monument.

Now known as the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park, the site has brought new awareness to the critical role Beaufort played in Reconstruction, or the period just after the Civil War when the country grappled with the devastating and lasting effects of war and how to integrate millions of newly freed slaves intothe country’s social, economic and political systems.

Now, a newphase is beginning for the project, says Beaufort Mayor Billy Keyserling, who spearheaded both the initiative and the advisory board of more than 100 local, regional and national advisors.

“So we’ve gone from being advocates for a monument to being advocates for a grassroots educational program,” said Keyserling.

The Long Road to a Monument

The effort to raise awareness of the critical role Beaufort played in Reconstruction wasn’t always a smooth one.

The idea to create some sort of monument or official recognition of the area’s role and historic sites began nearly 20 years ago with a visit from then U.S. Secretary of Interior Bruce Babbitt and historian Eric Foner.

Babbitt, who had read Foner’s book, “Reconstruction, America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877,” was the first person in his position to ask why Reconstruction was “entirely unheralded by the National Park Service,” according to an article in The Atlantic about the visit in 2000.

After a long struggle, including opposition from then U.S. Rep. Joe Wilson and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a renewed effort to establish a monument to Reconstruction was eventually revived in 2016 by U.S. Rep. James Clyburn and then U.S. Rep. Mark Sanford.

Clyburn had been a proponent of a Reconstruction park in South Carolina for many years and together, the Congressmen hoped to get the job done by way of a Congressional act.

Clyburn had been a proponent of a Reconstruction park in South Carolina for many years and together, the Congressmen hoped to get the job done by way of a Congressional act.

The proposal was met with overwhelming support at a community meeting held at the historic Brick Baptist Church on St. Helena Island at the end of 2016 and in January of 2017, the monument was finally created by President Obama, using his executive authority under the Antiquities Act. The monument was re-designated as a national historical park earlier this year.

Today, the park includes four properties in Beaufort County: the Old Beaufort Firehouse where the National Park Service is located, Darrah Hall on the grounds of the historic Penn Center and Brick Baptist Church nearby. Camp Saxton, on the grounds of the Naval Hospital in Port Royal, rounds out the list, but the site is not currently open to the public due to logistical issues and needed permissions that have yet to be worked out.

However, Keyserling and members of the advisory board are working with the United States Navy in hopes of eventually securing access to the site, so visitors will finally be able to see where the Emancipation Proclamation was read to a large crowd of Union soldiers and freedmen on New Year’s Day in 1863.

Though the Civil War would not be over for another two years, and another dark era shaped by restrictive Jim Crow laws would eventually follow Reconstruction, some of the first breaths of liberty were drawn by a newly freed people that day beneath the Emancipation Oak on the shores of Port Royal Sound.

It’s a moment in time, that many historians, educators and scholars alike, say is important to mark and to reflect on. Despite the tumultuous times that lay ahead, Reconstruction gave the world its first glimpses of a burgeoning nation trying to make good on earlier declarations that all men are created equal.

“Never before in history had so large a group of emancipated slaves suddenly achieved political and civil rights,” wrote Foner in “Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction.”

“Former slaves now stood on equal footing with whites, declared a speaker at a mass meeting in Savannah; before them lay ‘a field, too vast for contemplation.’”

The Power of Education

While the role Beaufort played during Reconstruction is a significant one, telling that story also comes with a certain degree of responsibility, said Keyserling.

“One of the things we were challenged with is, while putting so much focus on Beaufort, we don’t get to say it all happened here,” he said.

Which is one reason why the advisory board thought building or opening a museum to Reconstruction would be shortsighted. It was an expensive proposition, for one, but a museum would be static and perhaps fall short of illustrating the impact the era had on the nation as a whole.

Instead, the group hit upon the idea of a grassroots educational program, or series of programs, that would work with other groups and organizations to “uncover the truth” and “teach missing parts of our nation’s history.”

that would work with other groups and organizations to “uncover the truth” and “teach missing parts of our nation’s history.”

“With a museum, you have to go there and it stays there,” said Keyserling. “This we can take out there. This spreads.”

One of the first programs to emerge from the effort, called Story Catchers, works to teach middle and high school students real-world journalism and documentary-style skills while equipping them with the ability to share and pass on the area’s history.

Another initiative, called Children Teaching Children, uses visual arts, music or storytelling to help children teach other children stories from their history. The program has resulted in a children’s choir, led by Marlena Smalls, Eric Crawford and Karen Harmon, with plans for a community concert this September.

For the Teaching the Teachers program held at the Santa Elena History Center, rather than re-invent the wheel, Keyserling reached out to Massachusetts-based nonprofit Facing History and Ourselves, which already had a unit on Reconstruction.

The international organization, which focuses on educational and professional development, hasled the way in innovative programming designed to help educators tackle some of history’s most difficult topics such as the Holocaust, genocide and mass violence, Civil Rights in America and many others.

Through historical understanding and critical thinking, students are encouraged to explore the complexities of history, think about their connections to current events, and reflect on how choices – whether it’s the choices made by a single individual or the choices of a nation – have impacted history.

“We often find it’s small choices that build to these momentous times in history,” said Jeremy Nesoff, an associated director with Facing History and Ourselves who led the Beaufort training.

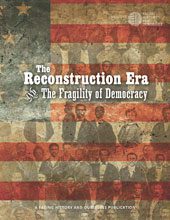

As members of the mixed-race group sat around a large conference table examining the image on the front of the program’s text, they talked candidly about their own experiences with learning and teaching American history.

The image, from the Library of Congress, depicts African American and Radical Republican members of the South Carolina legislature in the 1870s. After the Civil War, South Carolina had the first state legislature with a black majority, but the photo was created by opponents of Radical Reconstruction intending to scare white citizens into returning to an all-white legislature.

The organization’s methods and practices are based heavily on research, case studies, and primary and secondary source documents that are then discussed and given closer examination in the classroom setting, Nesoff said.

“It’s not about recruiting (students) or teaching to the test. It’s about developing critical thinking skills that allow students to find meaning through primary historical documents and discuss the significance of them,” he said.

Keyserling believes these kinds of educational initiatives can be transformational, not only for a community but for the country as well.

“Teaching students the untold story of the second founding of America will serve as the model to help transform the country with lessons started here in Beaufort,” he said.

Elementary school teacher Willie Turval, who also attended the training for the pilot program, agrees.

A fourth grade teacher at St. Helena Elementary School, Turval said he’s already seen what similar programs and curriculums that feature aspects of African America history have done for his students.

His students have entered his classroom in the 8th percentile on state testing but have left well above average at 63 percent, he said. He believes the jump in performance can be traced to programs that give students a sense of who they are.

“Sometimes we go to the expectations of ourselves instead of who we can be,” he said. “But with this, it’s a different pathway to success. It’s giving them a better sense of self and their place in history.”

Mindy Lucas is a staff writer for The Lowcountry Weekly and reporter for The Island News.

Learn More

To learn more about Reconstruction in Beaufort, visit the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park in the Old Beaufort Firehouse at 706 Craven Street, Beaufort or visit www.reconstructionbeaufort.org.