Sallie Ann Robinson talks about food, family and growing up on Daufuskie

Sallie Ann Robinson talks about food, family and growing up on Daufuskie

By Mindy Lucas, Staff Writer

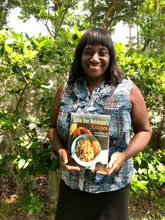

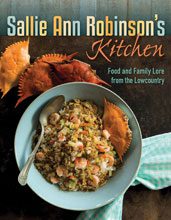

Local author and celebrity chef Sallie Ann Robinson is the author of three cookbooks, Gullah Home Cooking the Daufuskie Way, Cooking the Gullah Way, Morning, Noon, and Night and her latest, just released in September, Sallie Ann Robinson’s Kitchen – Food and Family Lore from the Lowcountry.

A sixth generation native of Daufuskie Island, Robinson has also co-authored Daufuskie Island (Images of America) with Jenny Hersch and was a contributor for Our Prince of Scribes: Writers Remember Pat Conroy.

Her connection to the late author is the stuff of legend. Robinson was one of Conroy’s students during that now famous year he taught school on Daufuskie. The trials and tribulations of that year waslater chronicled in his memoir, The Water is Wide, and Conroy and Robinson laterbecame close friends as Robinson began writing about her own life.

We recently sat down to talk more with Robinson about food, family and growing up on Daufuskie.

Lowcountry Weekly: So I think I told you when I first moved to the Lowcountry, I was so proud of my Beaufort status that I went right out and got my library card. And your cookbook Gullah Home Cooking the Daufuskie Way, with the intro from Pat Conroy (2003) was the first book I checked out. I also had this idea I was going to learn how to make biscuits, which never happened.

But your book did more to introduce me to the culture of Daufuskie and a sense of what the Lowcountry is all about than some of the books on local history I also checked out around then. What do you think of that connection between recipes and that sense of a place or who a people are?

Robinson: The lifestyle I grew up with, food was the center of everything – coming together, happy times and sad times. We had food during happy times and we had food during mourning times.

For me, food connects people. It also gives them the feeling of comfort because it soothes the soul. You sit down to a good plate of whatever – fried chicken, red rice, collard greens, lima beans – you kind of forget the bad stuff for that period. You aren’t sitting there eating mad. (laughing)

LW: You are so right.

Robinson:You are sitting there happy. That’s why I love cooking the way my mom and my grandmom used to cook and, like I say, it soothes the soul. It gives you something more to think about in a positive way.

LW: As an author, a chef and cultural historian, you certainly have earned a place of standing in the Lowcountry all on your own merits. Do you ever get tired, and that’s probably not the right word to use, but tired of getting asked about your connection to Pat Conroy, or do you feel it’s just part of your story now?

Robinson: I don’t ever get tired of sharing, because I don’t think enough gets shared. I want to open doors for kids, like Pat did, or anyone out there who isn’t sure of who they are, that food can actually help give you some identity. Especially the way you eat, whether it’s African American, or out food from out West, it identifies who you are.

But food brings me back home. It identifies the way I grew up, and that’s why I cook and I love sharing that. My mom used to be a cook on the side when people would come and say, ‘Who can we get to cook food?’ She would fix all this food and people would say, ‘Boy this is so good.’ I liked to see her stand around after cooking. She would just be smiling. People would appreciate the love she added to it, and so I cook with love.

And I love being in the kitchen. I can have my worst day, and I can get in the kitchen and have the best day ever. All because I am doing something great, because by the time I’m finished and I feed my soul, I am fine. I have no worries.

But do I get tired of being asked about Pat Conroy? No.

LW: The reason why I ask that too, is he had such a big personality, as you know, that you are  one of the only people I know that in your own quiet way were able to shine just as brightly as he did, and you know that takes a lot. (laughing)

one of the only people I know that in your own quiet way were able to shine just as brightly as he did, and you know that takes a lot. (laughing)

Robinson: We were friends to the end, honey. Friends to the end.

I was in 6thgrade when he came into our lives. My life I should say. What he brought to my heart, and my body and soul, never left because Pat was so sincere in making sure that we learned things that were beyond our island. And he just wanted us to be safe, and he wanted us not to be afraid, and he was teaching us how you can make it beyond this island, even though this island is all we had.

I tell people all the time it touches me every time I think about it because to me, he was such a big-hearted person, and he was such a big-hearted person when he didn’t even know it.

I have seen this man sit and sign, hundreds and hundreds of books, and give each and every one the love and attention they didn’t even expect to get. People stood in line for hours and by the time they got to him, he just cheered them up.

LW: Did that leave an impression on you? I mean, now that you are an author who signs books?

Robinson: Oh it did. You do it but not only do you do it for you, you do it because you’ve made so many people happy. Making people happy ain’t the sweetest job there is. (laughing)

But you know, all he wanted was the best for us. And the reason he got fired was because he was doing what he felt was best for us, and our parents did not deny those things. I know my parents loved him, because he did things that no other teacher did for us before him.

Every teacher has their own unique way of teaching children. Pat had something special. I know things today only because he taught us and never was taught those things before by anyone else.

LW: What are some memories that really stood out to you about that time, whether it was being a student at the Mary Fields School or just in general?

Robinson: He knew we were missing a lot of what we were going to have to face once when we left here. He wanted us to connect the dots.

I’ll give you an example. Pat knew we knew music, but we never knew the instruments that played the music. He was like, “Kids, it’s OK to love your music. But how do you know what kind of instrument is playing?” We couldn’t identify those things.

And that was special, because he was giving us an opportunity to say you can be and do anything you want, but first you’ve got to understand what it’s about. If you don’t understand what something is about, you don’t learn it, you don’t appreciate it, and you don’t get anything out of it.

LW: It sounds like he was trying to teach you not just things to remember or memorize, but how to figure things out for yourself?

Robinson: Yes. Now our parents taught us survival, or how to do things you need to do to survive like how to cut wood, or hunting, fishing or cooking. But they didn’t know book work, or how to teach us the educational part or the part that mattered more beyond this island than on the island because what we were learning mattered here. But what Pat was teaching us was going to matter once we got over there.

LW: How did you learn to cook?

Robinson: My mom had five girls and she met my stepfather who had five children from his deceased wife. But when he met us, I was the baby at the time at four months old. And then they had a set of twins to top things off. (laughing)

My mom and my pop could really cook, and what we used to love is that they were sometimes in competition in the kitchen. It was funny.

Pop loved fish. He’d tell her, “OK, put the grits on, because I’m bringing fish home.” Nine times out of ten it was mullet. He used to love to cast, and the reason he loved to cast is because he used to make the net.

Never one day did I recall being hungry for anything. We used to grow the biggest gardens. These were fields, we used to call them, not gardens.

It was a tough love situation, for kids, but when it came dinnertime you forgot you did all that work, because that meal was just that good. And you did it day after day.

LW: Do you remember learning to cook one particular dish, or were you always just cooking as far back as you can remember?

Robinson: Mom would always take a couple of us, not all of us, but she would be in the kitchen and she’d say, “Sallie come in the kitchen.” So I had to get in that kitchen and help prep stuff for her while she was doing other stuff like cutting up something.

Robinson: Mom would always take a couple of us, not all of us, but she would be in the kitchen and she’d say, “Sallie come in the kitchen.” So I had to get in that kitchen and help prep stuff for her while she was doing other stuff like cutting up something.

In the country, there was always something to do. She would say, “Stir that pot or watch that pot.” And watching the pot you learned texture, you learned smell, you learned taste, and she’d come in say, “Let me see what you done done.”

And if it was good, she’d say, “Yeah you did it right.” But there was no hug and, “OK you did it!” No, you had to keep doing it. You couldn’t just do it one time to prove a point. You had to keep doing it and they wanted you to get it right all the time.

And that was their way of giving us the kind of love that, you didn’t get a hug and hear my mom or pop say, “I love you,” but through all the food and the work and everything we had was all the love you could ever want.

LW: When did you realize your cooking was something special?

Robinson: After learning how to cook being at home, I left home to stay with my aunt in Savannah, and one day I told my aunt, I said, “You can’t cook like my momma.” And she looked at me and said, “Then you need to go home to your momma.”

LW: (laughing) This was your mom’s sister? Oh boy.

Robinson: Yes! Kids are honest. One thing about kids, they are honest until they learn to lie. (laughing)

But with that and as I grew older, I couldn’t find that flavor, that taste. When my mom cooked, you knew you was going to get a belly full and you knew you were going to enjoy it. There were no ifs, ands or buts about it.

I told myself, “Why are you complaining about how other people cook? You were taught to do this.” So I would cook like my mom used to cook different dishes. My kids ate good. Matter of fact, when they would leave home, and they come back, they would say, “Mom, you don’t cook like you used to.”

I’d say, “You don’t live here anymore; why should I?” (laughing)

But the first meal I learned to cook was fried chicken. But first I had to go in that yard, kill that chicken, clean it, and then cook it, and have it right, while they went fishing and crabbing, and have dinner ready for them when they got back.

Pop would say, “Y’all girls going to learn how to cook and clean. That way you can get a good man.” And my mom would come running out of the kitchen, and say, “Uh uh, y’all girls going to have to learn to cook and clean so you won’t starve.”

They wanted the best for us, but they were limited on what they could teach us. But the cooking, and the cleaning and the surviving part, they had that down pat, because that was an everyday way of life.

LW: Were you older the first time people complimented your cooking, or when you thought ‘I might be able to make a career out of this’?

Robinson: My kids would always bring friends to the house. They would bring friends home that would say, “Oh Ms. Sallie, this is so good.” And it would make me proud because, you know, your kids won’t tell you how good your food is. They’ll just eat it and say, “Well we eat this everyday.” But for somebody who has never had that type of cooking, it just takes them to another level.

I have a story in my first book called ‘Runaway Fried Chicken.’ I named this recipe after the first time my mom made me cook fried chicken; well she didn’t make me, she just told me, and I had to do it.

So when she and Pop would go to the river to go fish or crab they would go early in the morning, and wouldn’t come back until 3 or 4 in the evening. And when they come home they were hungry even though they would have taken a sandwich or something with them.

So the oldest at home had to prepare something they wanted that was going to take too long for them to do once they got back home. She would have already spent time with you from 8 years old – I tell folks from the time I could see over the woodstove. Because that’s how I learned how to cook on a woodstove.

There was no adjusting temperature, and you had to be on top of putting wood in that stove. They taught us, “You ain’t got time to play, you got to get in here and watch that pot, so it don’t burn.” (laughing)

You had to stir it when it needed to be stirred, add whatever needed to be added. Just things that most people take for granted. But they did not take the little things for granted because that was what they felt, when we left home, we needed to know to survive, and they weren’t going to be there to hold our hands.

LW: Tell me about this new cookbook. What makes it different from the other two?

Robinson: My first cookbook talked about growing up as a child. My second cookbook talked about being older, but also, the one thing I added in that book was 25 home remedies, because when we got sick on this island, we didn’t run off to go to a doctor because we didn’t have them here.

So my mom and them knew a lot about herbs and different things you could do if something came up. It’d have to be an extreme emergency to get you off this island for a doctor. Seriously.

They didn’t have the money and they knew that their medicine was better than anything, I got to tell you. And realizing how little they had but did so much with it, it made me proud. You can live in an area, and act like you don’t know about things, but you will not survive! (laughing)

Our parents wanted us to really understand that first, it took really paying attention and having manners and respect for nature, because believe me, if you didn’t have that, then… We didn’t kill animals just to kill them, we killed them for a purpose – for our food. We didn’t abuse those things. We were not taught to do that. If you kill something then you doggone well better eat it.

In my new cookbook, I have a lot of different ways to cook some of the things in the other books, and I have recipes that, as I got older, I did myself. I just learned to wing it, and it turned out so good! (laughing)

But it always has my mom’s way of thinking in it, because that’s how I cook a lot of times. (I’ll say), “What would mom do if she had this and this?” Because that’s how she made me realize, you can do it. There’s nothing you can’t do, it’s just taking the time to say, how do you want it?

Yes, I’ve burned a few rice pots, but I learned that my attention had to be on what I was doing for the time it needed and also to perfect it.

I cook a lot for myself. I feel like I have a great palate. I don’t like a lot of salt. I’m not an overly spicy person even though from time to time, I love spice, but I don’t want it all the time. Like a little hot sauce on something or, right now, I do hot pepper and vinegar. But we couldn’t put that on all our food. We weren’t allowed to.

We grew the peppers. The only thing my mom bought was the vinegar, so we couldn’t just eat things that she’d have to contribute to when it came to the money part.

Like sugar? We never ate a whole lot of sugar. The only time my mom made dessert was on Sunday. We ate a lot of fruit – pear trees, plum trees. We had sassafras tea, and it’s very tasty.

But learning to cook wasn’t just something you did. It was something you prided yourself in and you cooked with love.

LW: You frequently conduct cooking classes or demos as part of the press tours around your  books. Tell me what that’s like, the teaching part.

books. Tell me what that’s like, the teaching part.

Robinson: I hear a lot of people say I don’t know what to cook, and I think, “What you mean? It’s right in your face!” (laughing)

Folks just turn their noses up at things they never try. I put fried ribs in my first book and many people had never heard of fried ribs. They’d say, “You can fry ribs?” I’d say, “You can fry anything.” (laughing)

But I like to teach to give, because I have a lot to give. I was taught a lot for myself so teaching for me is a way to give. But these events, I love to teach the old way of cooking because it was simple and I’m very proud of these meals. They got me through good days and bad days and in-between days.

To share the memory of my mom and my grandparents’ way of cooking just makes me feel so good. It’s a joyful feeling within me.

LW: Is there one thing or some things you think about now that you’ve had three books under your belt that you want people to know or a sense of cooking and the stories you might share along the way?

Robinson: …I want people to know that you can take almost anything edible and turn it into something fulfilling.

Food for me brings back those good old days and memory of a time that was hard. It was hard times, but we didn’t even know it was hard times. It also reminds me of what we had to do to make ends meet, and it gives me joy to know that my parents took the time to show me how to survive.

LW: And like you said, they may not have said every hour or every minute of every day, ‘I love you,’ but it seems like the ultimate expression of love to teach a child how to make it in this world.

Robinson: My pop used to say, teach a child from the moment they are born into this world, and they will make it in this world. You got a lot of people who don’t know how to survive in this world.

But they always gave us a reason, or there was always a method to the madness. Even though we didn’t always understand what all that was then, every day I saw it and I felt it and it made me realize I know this is why they said this.

LW: Is your mother still living?

Robinson: No, my mother died in 2013, and she is buried here on Daufuskie.

LW: Do you think she would proud of the things you just said – that when you cook or teach others, you are sharing the memory of her and your grandparents’ way of doing things with others?

Robinson: Yes. My mom was here when I wrote two of my books. I was actually writing my third one when she passed. I even have that in the acknowledgements.

But you know what was crazy though? She said, “Ann be careful what you write because those people will be mad at you.” I said, “Mom, what you mean?” I said, “Mom this is about my life, our life, the things you taught me. Nobody can take that away from me.”

I was teaching her something, and she was proud of me because she had so many people come to her, and tell her how wonderful my books were, and how they had learned to cook from them.

I would not have taken the time to write a book if I didn’t think I could teach somebody something and whoever is out there learning, that is my connection to my parents saying, “Job well done.”

Upcoming Appearances

Meet Sallie Ann Robinson at the Bluffton Book Festival from 6 – 8:30 pm, Nov. 21, at Billy Wood Appliance, 1223 May River Rd, in Bluffton. The event will include a cooking demo and tastings. Tickets are $49. For more information on the festival, visit www.blufftonbookfestival.com or visit Robinson at www.thegullahdiva.com.