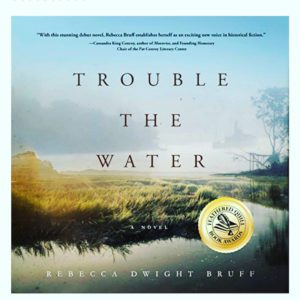

How Robert Smalls’ story inspired an award-winning novel that birthed a critically-acclaimed theatrical production.

Novelist Rebecca Bruff

It’s been a bittersweet summer for Rebecca Bruff.

In June, she lost her beloved husband and partner-in-adventure, Tom, after a long, debilitating illness. A few weeks later, a theatrical production based on her debut novel, Trouble the Water, opened to rave reviews at the prestigious Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum in Los Angeles.

So much sorrow and so much joy, side by side. Intertwined and inextricable. That’s life, as this Methodist minister-turned-author well knows. You might even say it’s the central truth at the heart of her award-winning novel.

The last five years of her own life read a little bit like a novel, in fact. In 2017, she and Tom pulled up the roots of their happy existence in Dallas and moved to Beaufort so Becky could write a book about Robert Smalls. It seemed an unlikely move – she’d never written a book before, and had only recently heard of Smalls – but there were mysterious, irresistible forces driving this narrative.

Tom & Becky Bruff in Rome, 2016

A little background. The Bruffs first visited Beaufort together in 2013, at which time they took the requisite carriage tour through downtown. There, in front of Tabernacle Baptist Church, they encountered the bust of Robert Smalls and heard the phenomenal story of this slave who became a Civil War hero and US Congressman. They weren’t sure which was more amazing – Smalls’ story, or the fact that they’d never heard it before.

“My husband Tom was a real history buff, but even he had never heard of Smalls,” says Becky. Intrigued, they headed straight for the library and local bookstores, looking for more information, but Becky wasn’t satisfied with what little they found. “I couldn’t find the book I wanted to read,” she says.

After that trip, “Robert Smalls really started getting under my skin,” says Becky. “There were so many unanswered questions. So many gaps in the timeline. I started doing research, making notes, not really sure what I was doing. Was I writing a book? I didn’t know. I just couldn’t get him out of my mind.”

Fast-forward to the summer of 2016 when the Bruffs were traveling in Cuba. “At

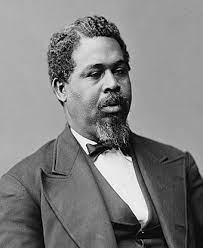

Robert Smalls

the time, I was reading Richard Rohr’s book ‘Falling Upward’ – you know, about the two halves of life? And I was still thinking about Robert Smalls. I remember saying to Tom, ‘I need to either tell this story and get it out of my system . . . or just get over it already.’”

The Bruffs returned from Cuba on a Tuesday, and on Friday there was a letter in their mailbox from a realtor who wanted to buy their house.

“I think it was serendipitous, divine, and just sheer luck,” says Becky.

Despite having family in Dallas, not to mention careers – Becky was pastoring at

a large church, Tom was a consultant – they decided to sell. They weren’t sure where they’d end up, but Beaufort seemed like the place to start if Becky was to properly pursue her Robert Smalls obsession. Tom was characteristically game – and he could work from anywhere – so Becky took a four-month sabbatical and they were off to the Lowcountry.

Within a couple of months, that “sabbatical” became a permanent move as the Bruffs faced up to two realities: 1) You can’t write a decent book in four months; and 2) They absolutely loved the Lowcountry.

In Beaufort, Becky had the good fortune of meeting Marly Rusoff – Pat Conroy’s longtime literary agent – who knew the story of Robert Smalls and had always wanted somebody to write it. Despite Marly’s connections, finding a publisher was no easy feat in an industry grown increasingly sensitive about cultural appropriation. Times were changing, and Becky was a white woman telling a Black man’s story. Publishers were wary.

“I was very flattered by the rejection letters I was receiving at first,” Becky laughs. “Here I was a new writer, and big publishers like Random House were actually reading my book! And they were saying things like, ‘Great story, great writing . . . We aren’t gonna touch it.’”

As the rejections kept coming, though, Becky grew frustrated. This story that had so captivated her – that had literally uprooted her and driven her across the country – was being dismissed, over and over, by publishers who worried that she was too white to tell it.

“At first I was defensive,” she says. “I thought, ‘It’s an American story! People who look like me have been scrubbing it from textbooks for a long, long time. That’s why I want to tell it!’ But I hadn’t learned how to articulate that yet.”

During this time, Becky had a small crisis of conscience. Or maybe just confidence.

“I’d begun reading about appropriation and representation and why it matters so deeply, and it does,” she says. “I started wondering ‘Who am I to tell this story?’ Then somebody sent me the author’s notes from Jodi Picoult’s Small Great Things. One of the characters is a Black nurse, and Picoult talks about her journey through that. It really helped me. I kind of went from ‘Who am I to tell this story?’ to ‘Who am I to withhold this story?’”

Confidence and purpose restored, Becky still didn’t have a publisher. “After the 5th call from Marly saying ‘somebody just took another pass,’ I said, ‘Okay, just forget it. I’m ready to give up.’ But Marly said, ‘No no no no no’ . . . and Tom said, ‘No no no no no’ . . .

Confidence and purpose restored, Becky still didn’t have a publisher. “After the 5th call from Marly saying ‘somebody just took another pass,’ I said, ‘Okay, just forget it. I’m ready to give up.’ But Marly said, ‘No no no no no’ . . . and Tom said, ‘No no no no no’ . . .

Soon thereafter, Marly found a smaller publisher, Koehler, out of Virginia Beach. They loved the book and said, simply, “Let’s do this.”

And so they did. Trouble the Water was published in June of 2019.

Koehler’s faith in the novel was not misplaced. Since its publication, Trouble the Water has garnered a slew of First Places – from the Feathered Quill to the American Book Fest to the Firebird Book Awards to the CIBA International Book Awards.

Even more important to Becky, perhaps, is that the book was warmly embraced by the Black community here in her own adopted town of Beaufort, starting with a wonderful book launch at Tabernacle Baptist Church, where it all began.

Fortunately, she was able to do lots of events during the summer, fall and holiday season of 2019 before Covid shut down the world in March of 2020. Then came the summer of George Floyd, and the novel gained a whole new layer of relevance.

At that time, Becky was about halfway through production of the Trouble the Water audiobook, working remotely with a friend of a friend – a Black theater actor and voice artist in California named Gerald C. Rivers.

Best-known for his portrayals of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, Rivers is a longtime company member of the celebrated Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum in Los Angeles, run by Geer’s daughter, Ellen. Like all the other theaters everywhere, theirs had shut down during Covid.

According to Becky, Ellen said something to Gerald like: When we reopen, I want to do some Black Lives stories. It’s time. I want you to bring me a handful of options.

Gerald Rivers brought Ellen Geer a stack of books for possible adaptation. She chose Trouble the Water.

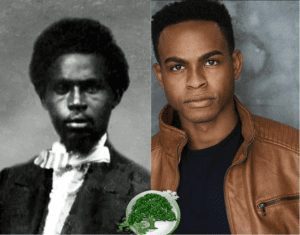

Gerald C. Rivers as Robert Smalls, elder statesman

Becky consulted on Geer’s script, which the reviews repeatedly refer to as “freely adapted” from her book. Becky says she’s quite happy with the script and doesn’t mind that it’s freely adapted. After all, she freely adapted Smalls’ life when she imagined it into an historical novel.

Trouble the Water opened this July, with Gerald C. Rivers directing and playing the elder Robert Smalls. (There are two actors in that role.) Critics have described the production using words like: Important. Monumental. Exhilarating. Tour-de-force.

The Canyon Chronicle says the show is “filled with trauma, small moments of joy, heartbreak and lingering tragedy,” calling it, “a theatrical stunner that brings the truth of America’s dark past up close and uncomfortable, yet we can be proud to see that someone like Smalls is part of our legacy of what freedom really means.” Showmag calls the play, “as sprawling as the sweep of this man’s life” and describes the cast as “stellar.” The raves go on and on.

Becky Bruff is headed to Los Angeles next week to see for herself. She can’t wait to meet Gerald Rivers in person – they’ve been Zoom buddies for a while now – along with Ellen Geer and the “stellar cast” that’s bringing Smalls’ story – her story – off the page and onto the stage. Late in September, she’ll return to LA for an author’s talk following one of the final productions.

Terrence Wayne, Jr. (right) portrays young Robert Smalls, aka “Trouble” (left)

“I keep thinking about Robert Smalls,” Becky says, her eyes a little misty. “What would he think about this story being told there? On that beautiful outdoor stage in California, in front of all those people, 160 years later?”

Yes, Becky is still thinking about Robert Smalls. She’s also thinking about what it means to be a storyteller. “Stories connect us,” she says, “but they can also provoke us. Stories can tear us apart.”

Our storytellers have always had a special kind of power, but in today’s hyper-connected world of overlapping, diverging, and conflicting narratives, perhaps that power brings with it even greater responsibility.

“There are a lot of ways to tell a story,” says Becky. “We’ve kind of canonized one way, and now we’re starting to say . . . ‘Wait a sec.’ I think about that a lot. That responsibility. The responsibility to tell stories in a way that cultivates conversation instead of stopping it.”

Musing on this fraught, complicated time in America, when so much of our common story is being reexamined and retold, Becky Bruff seems circumspect . . . but hopeful.

“There’s a lot of tragedy and loss in our story,” she says, “but there’s so much beauty, too.”

Learn more about Rebecca Bruff and her work at www.rebeccabruff.com

Learn more about the Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum at www.theatricum.com