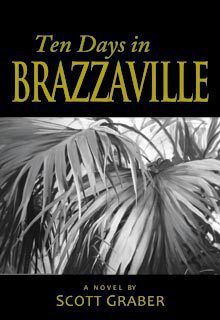

An excerpt from the new novel by Beaufort author Scott Graber

An excerpt from the new novel by Beaufort author Scott Graber

O N E

The envelope was there, in plain view, but he did not see it. Instead, his sleep-filled eyes went to a bookcase. His eyes always went to his bookcase.

His bookcase was eight feet tall and ran for twenty uninterrupted feet along his northern wall. This long run of American walnut was dark, almost purple in color and featured an ancient set of Blackstone’s Commentaries. Blackstone’s books were never opened—admittedly they were décor. They were secondary to a paper cup, a plastic valve, and ten other objects that were individually illuminated in a way that reminded Jake of Hittite burial objects at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

None of these artifacts were Hittite history. However, each of these objects was modern, machine-made and had failed to function as promised. When that explicit or implicit promise

was broken there were consequences. In the case of the valve, it was Emily Grant’s teenaged face. The young girl’s still-forming face was burned; so badly burned that multiple skin grafts would

always be a reminder of that broken promise.

Each broken promise consumed several years of his life.

Each demanded up front cash and was a gamble by Jake and his law partners. Each sucked marrow from his stiffening, middleaged bones and left him exhausted, wondering if there was another trial in his system.

After each trial there was the ceremony.

Surrounded by his partners, Jake would pour the first glass of Korbel and then tell a short, funny anecdote. Then he would turn away from his impatient partners and mount the toy truck, the failed object, above a black, hockey puck-sized disk.

Rigid, black-painted wires held the defective part above the disk and gave him a new war story—a story he was prepared to repeat when a client walked over to the bookcase and said,

“What the hell is this supposed to be?”

This morning Jake’s eyes went to the cup and he remembered the Cal Tech engineer who had testified the coffee cup was too tall, the cardboard too thin. But his expert’s

testimony had not been perfect: “When you say ‘discomfort’ aren’t you really saying it

hurts when you….”

“Objection. Counsel is leading his witness.”

“Aren’t you saying it hurts like hell?”

“For God’s sake Counsel,” said the red-faced judge. “How long have you been in this business, Jake? Surely you’ve been doing this long enough to know this man is your witness.”

“I’ll withdraw the question.”

He remembered his cross-examination of the selfrighteous, impeccably tailored CEO.

“It was a matter of per unit cost, wasn’t it?”

“Cost is always consideration but.…”

“But in this case it was the primary consideration.”

“Jesus Judge,” shouted defense counsel, “now he’s answering his own questions.”

He remembered the call from the unlucky associate who had been told to settle the case.

“We have a good shot at a defense verdict, but one can never be sure about juries these days; not around here. Our people want to avoid another two or three days of trial if we can

settle for an appropriate sum.”

“An appropriate sum?” Jake repeated. “And what do you consider an ‘appropriate sum’ in US Dollars?”

“I think our client will agree to $850,000,” said the young man.

“You think your client will agree to $850,000,” he repeated. “When do you think your client will actually decide that $850,000 is appropriate?”

“I have authority to put $850,000 on the table,” said the lawyer. “I’ve got that authority today. Now.”

“I’ll take $850,000 to my client—as I’m bound to do— but she won’t agree to that number,” Jake said.

However, his client had liked the number. After two days of trial, most of his clients lost their anger and were ready to take the money. You could practically see the dollars flapping in the wind as they sprinted away from the courthouse.

“Yes. For God’s sake, yes,” she had said.

“We’ve got to wait,” he said taking her hands in his own.

“This is their first number. They know we won’t take $850,000 and they’ve got a second number. Actually, they’ve got a third number, and what they think is their final number.”

“I’m not sure I can take another day of this torture,” she said. “Let’s just go to their ‘final number’.”

“It’s not good enough,” Jake said.

“This has got to stop,” she said. “I’m not tough. Not like you.”

“You are tough,” he said. “And this is meant to be hard. It’s meant to discourage people. That’s why it’s called a ‘trial’.”

He remembered the surge of electricity that galvanized his body when the foreman replied, “Yes, your Honor, we have reached a verdict,” and the agonizing 10 second delay when the foreman handed the small, folded paper to the judge. The 15 seconds it took for the judge to silently read the verdict, gaze at the ceiling, and then pass the verdict back to the Clerk who read it: “We find in favor of the Plaintiff in the amount of $4.5 million dollars.”

As he sat in the darkness, he remembered some of the panicked words that came from the defense table: “ludicrous”… “outrageous”… “embarrassment”… “we’ve got to appeal”.

“You knew,” she said. “You knew how it would end.”

He remembered her words, “you knew”. He remembered the adoration in her eyes; her sense of wonder; his sense of control. Now he wanted to feel that way again. He wanted to feel that way soon. He didn’t see the envelope.

T W O

Slowly, his eyes moved away from the bookcase and made their way to the wide-matted, thin-framed photographs he had carefully arranged on the far wall. On that wall, a rough brick wall that he had refused to panel or sheetrock, he had mounted photographs that acknowledged his attractive family, and demonstrated he spent time with his wife, Emma, and their two exceptional girls. His dedication to family was evinced by a dozen black and white photos: ten days on the Snake River; two weeks in Chaco Canyon; a hiking holiday in the Italian Alps. These images confirmed that he was an attentive, involved father who gave more, much more than what was normally expected from a busy, over-extended trial attorney. They attested to the fact that his girls still talked to him, trusted him with their secrets and, in fact, found him relevant. These images were secondary to another

group of photographs.

On the third wall a photograph showed the trial lawyer with South Carolina’s young, just-elected Governor. Governor Lewis had his arm around Jake’s waist and was whispering into his ear. The image conveyed something more than the usual gratitude that comes after the discrete delivery of a campaign contribution. The image, in fact, suggested an intimacy reached over prolonged, bourbon-laced conversations that went well beyond baseball scores or the price of gasoline. There was the suggestion, in the photo, of a history between these men. An uneven history. If there was any lingering doubt about Jake’s access to the Governor there is an inscription: You were with me in the beginning when my name was not known. Your early support will not be forgotten by me or

those who work for me. You have my direct telephone number.

A second 8×10 featured Jake and South Carolina’s junior senator, a man who had been his college classmate and another relationship that went beyond campaign checks. This relationship included a midnight telephone conversation with an upcountry sheriff who came upon a semiconscious, sobbing,

apparently uninjured man who occupied an over-turned Buick; a man who happened to be a US Senator. In this long-ago conversation, Jake reminded the young sheriff of law enforcement legislation then working its way through the Senate. He carefully catalogued the slobbering man’s legislative achievements and the jobs he had brought to upstate South Carolina. While making no promises, or proposing any deal, he suggested that restraint and, perhaps a little empathy, would be rewarded at some unspecified time in the not-so-distant future. It was a relationship not well-served or well-described by the Senator’s hurriedly scrawled inscription: To my friend, Jake Timrod, who will always be my compass, ballast and counsel.

“Compass,” he thought. “The man has no compass, moral or otherwise. And the only ballast this guy has is an everexpanding belly that hangs down between his huge thighs.”

The well-framed photographs and the well-lit objects reminded Jake of what he had  accomplished—what he had done as a trial lawyer. The objects and images were the high water

accomplished—what he had done as a trial lawyer. The objects and images were the high water

marks of a life characterized by confrontation; proof that he had that uncommon, elusive elixir called courage. And, as far as he was concerned, courage was what mattered. Jake was willing to endure the cocktail party jokes that connected lawyers to hyenas; or hogs; or most often, sharks. He listened, but rarely smiled at these naive people who didn’t understand that someone had to expose cheaply made toaster ovens and SUVs that tipped over too easily. He didn’t want to be around self-important doctors who did not know, or would not admit, that trial lawyers had beaten Big Tobacco, and a dozen other companies who manufactured cancer. He didn’t want to be near people who had never stood in front of a jury and explained negligence, proximate cause and why the companies that made tire rims had to be accountable when their product decapitated a teenager.

Nor did he like lawyers who sat behind large desks and filled-out forms. He had no interest in wills or trusts or deeds or the term, transactional lawyer. He wasn’t interested in deals, deferring taxes or helping the rich shelter or manage their wealth. No, he wasn’t that kind of lawyer. Several times each year Jake pulled-out a dark blue, hand-tailored suit and went head-to-head with corpulent, conservative men who got their $400 an hour fee regardless of the outcome. He fought these self-righteous, sanctimonious bastards with an intensity that usually brought a warning: “Take it easy Counsel. Take a deep breath. This might be a good time to adjourn for lunch.”

However, something was not quite right these days. There was, in fact, uncertainty running loose in his psyche; and that uncertainty brought anxiety along with it. Jake knew that anxiety was a chemical thing and that many lawyers—good lawyers—got careful and cautious as they got older.

“You settled for $50,000!” Jake had said to his friend, Homer Pettigru, earlier that week.

“Yeah. Right. I had good facts, good liability, but the damages just weren’t there, “Pettigru replied.

“I thought you had $25,000 in medicals?”

“Yeah, but my doc didn’t do well at his deposition. He said my man should have gotten better sooner. He said his objective findings didn’t support the length of his recovery.”

Jake and Homer knew that this was a good case and that Homer was getting increasingly cautious and his caution was going to end his career.

Now, especially at night, Jake was having his own problems. Earlier that week, as he lay in bed just on the edge of consciousness, he decided he had forgotten to answer Requests to Admit. The Rules say that if you fail to answer such requests —within 30 days—they are admitted.

As he lay in bed, he was certain he had not answered within the required 30 days. By midnight he had convinced himself that he’d “admitted” facts that he could not admit. At two in the morning, he decided that Judge Elbert Eddings would not let him correct his mistake. By three, he had convinced

himself that he’d put his entire case into jeopardy. At five, just as the sun was streaking the South Carolina sky, he raced to his office where he discovered he had, in fact, answered. His heartbeat went back to normal. His hands stopped shaking. But he was angry. Furious. Was he, like Homer, losing

his courage? Was it dripping out of his body like a leaky faucet?

* * *

“You haven’t opened your mail,” Benjamin said as he walked into Jake’s office.

“What mail?” he replied.

“The letter that’s on your desk…”

Jake looked down and saw an envelope. He stared at the handwriting thinking he had seen it before. He was, however, distracted. He couldn’t focus and was annoyed that Benjamin, his associate, was watching him. He put the envelope down.

“I’ll read it later,” he said without meeting Benjamin’s gaze.

He wanted the boy out of his office before he opened the letter. Actually he wanted the boy out of the firm. Benjamin McMaster was a baby-faced academic—he looked at both sides of every issue. He didn’t have the singleminded, one-sided focus that was essential in a trial attorney. He was too soft, too accommodating, and too quick to concede the point. He wasn’t an advocate. He wasn’t a warrior. Jake wanted him gone.

A litigator had to be convinced he was going up against the forces of evil. He had to believe that American corporations had no capacity for caring; compassion wasn’t part of their DNA. These were bad people and you hit bad people with a pressure treated 4×4. If that didn’t get their attention, you

rammed it up their ass. Jake understood this fundamental truth.

Benjamin, thus far, did not.

Anger, indignation and, yes, a certain amount of detachment made a trial lawyer. The anger couldn’t be apoplectic rage that shut down one’s ability to think. But a seething sense of injustice and a measure of controlled rage was fuel for those who went to court. This boy didn’t have that fuel.

“We’ve got to answer some interrogatories,” said Benjamin.

“You’ve got to answer some interrogatories,” Jake said, correcting his associate. “And for God’s sake don’t give away the store. If they don’t ask the question, don’t answer the question.”

“But the Rules say…”

“I don’t give a damn what the Rules say,” Jake said. “If they don’t ask, you’re not under an obligation to answer. I don’t want you volunteering information they don’t specifically request. Do you understand that? Do you understand what I’m saying?”

As Benjamin left, Jake picked up the envelope.

T H R E E

Once you said you loved me. Once, a long time ago, you said you could not live without me. When you said those words, I think you meant what you were saying…

Now his eyes were racing to the bottom of the page. And when they found and fixed on her signature, Sarah, he was transported to a table in a candlelit restaurant in Colonial Williamsburg.

He remembered that the room was dark, too dark, and he hadn’t been able to really read the menu. He hadn’t eaten his food. He hadn’t been able to see her eyes when he said those words.

I have thought about this letter for a long, long time. And for a long time I have resisted the urge to write you. I can’t resist that urge any longer.

Jake Timrod met Sarah Moss when he was a freshman at The Citadel and she was a sophomore at William and Mary. In the beginning their relationship was entirely postal—he had gotten her name and address from a friend. At first, their relationship centered on his long, anguished letters complaining about his life at the military college: he was not doing well; he didn’t understand why he couldn’t get his “shit squared away” or why he was disliked by his classmates.

His letters were written late at night with a blanket stuffed into the transom to block out the light from his desk lamp. After lights-out a cadet was required to be in his bunk.

Theoretically, he was required to be asleep too. A sword-wearing officer walked the galleries making sure that everyone was in his rack.

Few freshman cadets could afford the luxury of sleep. Most were academically deficient and used this time to memorize a sonnet or the periodic table. Others, like Jake, were shining shoes or brass buckles or their collar insignia— desperately trying to stay militarily proficient. However Jake still

took time, some of this precious, illegal, brass-polishing time to write Sarah.

Almost every letter described the push-ups, pull-ups and beatings with a broom handle as he hung from the water pipes. He described the “sweat parties” where one was required to put on a full dress uniform and report to the shower room. There, with the hot showers going full tilt, one was required to run in place holding an M-1 rifle at arm’s length. He described the yelling, the steam and the strange serenity that came just before he lost consciousness and fell on the white tiled floor.

His letters described a cadet who would rather read Updike or Welty than study Jackson’s turning movement at Chancellorsville. His letters described the 2nd class cadre and their determination to drive him out of the Corps of Cadets. He wrote with the passion of a revolutionary—and this passion

worked with Sarah.

Jake was careful not to appear too pathetic or come off like some kind of psychopath who would seek out a water tower and go on a shooting rampage. He was misunderstood by the upper class and unappreciated by his peers. But his letters always ended on a hopeful note. Soon that hope was entirely built around Sarah. Yes, Sarah was someone who finally understood him and his tortured life.

Although they talked on the telephone, Jake was best with pen and paper. He was at his best when writing a story—in his case an ongoing tragedy. After mailing his letter he would anxiously wait for her reply.

From time to time Sarah would come down from Williamsburg; or he would drive up from Charleston. These weekends never lived up to his expectations. Their one-on-one conversations were never as artful as the written word. Sometimes, after her visit, he would sit down and write her a letter that said what he had not said; or should have said; or meant to say. It was as if he had to correct the record before their relationship could go forward.

I have always wondered what might have happened if you had argued with me, really fought with me and refused to end our relationship. I was surprised when you didn’t try harder….

Sometimes when he was alone with a gin and tonic he wondered the same thing. Should he have fought, kicked and screamed when she said, “This isn’t working is it?” He wondered what course his life might have taken if he had persuaded her to stay with him. He knew that he could have persuaded her if he had really wanted to. But something in him said, “Stop. Enough. Let it end.”

After a second drink he would remember her passion—a passion that was an indistinct notch shy of anger. He would remember that she was opinionated and their marriage would have been a series of struggles that would have left them both dazed and bleeding. And yet he would always wonder if being married to this extraordinary girl would have been worth the pain that came with Sarah’s passion.

I’m happily married and do not intend to tell my husband about this letter or this request. My husband is a good, decent man and I have no right to destroy his happiness…and this letter would do that. And so, right here on the front end, I’ve got to ask you for your discretion. Do I have that? I must have that assurance.

Sarah would have his discretion. She could have anything she wanted from him.

I have lost my son. No, to be honest and precise, we have lost our son…you and I.

As he reread the two words, our son, Benjamin reappeared at his door.

“What’s wrong, sir? Are you sick? Should I call an ambulance?”

####

“Ten Days in Brazzaville” is available locally at The Beaufort Bookstore (Beaufort Town Center) and McIntosh Book Shoppe (Old Bay Marketplace, Bay Street). Order the book online at www.lulu.com or download it as an eBook at www.amazon.com. For more information or links to online purchase sites, visit www.scottgraber.com