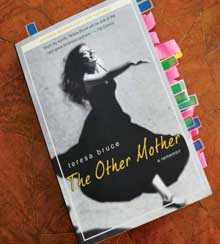

A conversation with award winning Beaufort writer Teresa  Bruce about her upcoming book, “The Other Mother,” and the transformative power of chance encounters.

Bruce about her upcoming book, “The Other Mother,” and the transformative power of chance encounters.

Many years ago during his travels in Africa, Ernest Hemingway got to know a fearless young woman named Beryl Markham who showed him a bit of a memoir she was working on. The notoriously egocentric Hemingway immediately dashed off a letter to his editor, the legendary Maxwell Perkins. “She has written so well, and marvelously well,” Hemingway concedes, “that I was completely ashamed of myself as a writer. I felt that I was simply a carpenter with words, picking up whatever was furnished on the job and nailing them together and sometimes making an okay pig pen.”

This is sort of how I feel about my friend, Teresa Bruce.

“For a brief, thrilling moment, the Whale Branch River Bridge releases all who travel over it from gravity. You look down from an Osprey’s eye view into a fish-full ribbon of life. The water is a shimmering membrane, wide and porous. Salt and sweet, past and present glide through in opposite directions.” – From “The Other Mother” by Teresa Bruce, copyright 2013, published by Joggling Board Press

See what I mean? This was her first impression of the Lowcountry driving into Beaufort as a young reporter for WJWJ TV in 1989. Soon after, she met Byrne and Duncan Miller and everything changed. The Millers were not your typical Beaufortonians. They were exotic elders, bohemians from another age. Byrne wa s a pioneer of modern dance and founder of her eponymous local dance theater. Her career took root on the burlesque stages of the Great Depression. He was a pioneer, as well, one of the original Mad Men of Madison Avenue and a deeply frustrated novelist. Teresa soon finds that she’s been “collected,” joining scores of other “brothers and sisters by Byrne.” Her book – her “rememoir” – about the complicated relationship with her Other Mother gets a local release in September followed by a national rollout November 5th. Critical buzz is already building.

s a pioneer of modern dance and founder of her eponymous local dance theater. Her career took root on the burlesque stages of the Great Depression. He was a pioneer, as well, one of the original Mad Men of Madison Avenue and a deeply frustrated novelist. Teresa soon finds that she’s been “collected,” joining scores of other “brothers and sisters by Byrne.” Her book – her “rememoir” – about the complicated relationship with her Other Mother gets a local release in September followed by a national rollout November 5th. Critical buzz is already building.

The following interview took place on Sunday afternoon in the house the author once shared with Byrne Miller, one she now shares with her photographer husband, Gary Geboy.

Teresa Bruce: [The book] is kind of memoir – slash – interpretive biography in the sense that I tell my story of the young Teresa Bruce when she showed up in Beaufort at twenty-something, and then Byrne’s story. But Byrne’s story begins much earlier. The paths are not parallel. They’re like two movements of a dance and they eventually intertwine and the story zigzags back and forth. How do I get in her head and make this happen?

[Thinking of] the book as a dance in two movements really, really helped it jell conceptually for me because it was hard. I mean it’s about a woman whose story begins fifty years before I’m born. So how do I tell that story? I wasn’t there. I wasn’t part of her extended family. She’s not famous. There aren’t tons of biographic or archival information. What there is is at the library, and I used a lot of it.

Mark Shaffer: As you mentioned, Byrne’s not famous or all that well known. What makes her important?

TB: That’s a really good point. She is important. In some way or another I think she changed the lives of everyone she was close to that she sucked into her circle. Wherever she lived and danced around the world – and there were many places – she said that she “collected” children. It started out that they were dance students and then gradually, as she got older and moved into presenting dance rather than performing, it wasn’t so much dancers as media people, reporters, writers, other artists and people in the larger community. She just had this amazing thing. I call it an exuberant positivity. She had exacting standards. She did not suffer fools gladly. She had no patience for mediocrity of any sort. One of her sayings, which I call “womenisms” in the book, is “mediocrity is distasteful.”

It wasn’t like she was that woman who was so nice and complimentary to everyone. She was not that person. But she drew out what was special in you and what your dreams were and what your ideas were and she somehow made you feel like you could do it.

She had such incredible challenges in her life and she managed to overcome them through this sheer force of will. Another womenism is “she had a whim of iron, and it rejects rejection.”

MS: I love that.

TB: A whim of iron. If you said “no” she would say, “Okay, then. How about this?” She would not give up.

People always thought she lived this sort of charmed life because she had this idyllic marriage to this wonderful, sincere, intellectual, kind man.

MS: It was anything but idyllic?

TB: No. It was idyllic in a way, but she made it idyllic. She overcame so many things. I think the book is going to be a big surprise to people who only knew Byrne in one capacity as this figurehead of this amazing dance theater. They’ll discover that the woman behind that confident façade was a really complicated person who had to battle for everything.

She grew up in an upper middle class Jewish immigrant family in New York. When she married Duncan she was very young. She was older than he was, but she was very young and they were in the Great Depression. They had nothing. They had to scratch for everything. She had two daughters. One was killed by a drunk driver and the other was diagnosed with schizophrenia as a four or five year old. And that was back in the day when the treatment was electroshock therapy. And she married a man who had . . . issues. He suffered with mental illnesses, too. She had to cope with all these things and yet still achieved so much with such positive energy. She was a force of nature.

MS: What drew the two of you together?

TB: Well, it’s funny. I’m a dancer – had been a dancer – and people always thought that’s what connected us. But I was actually a reporter for WJWJ TV and I was assigned to cover Duncan Miller, Byrne’s husband who was getting experimental Alzheimer’s treatment at the Medical University of South Carolina. Byrne had orchestrated a public relations assault on the university because they had discontinued his treatments. What drew me to her was this amazing love between them. I had never witnessed something like that. It was literally transformative. You were just in awe of this power couple who were so gentle and committed to each other.

At the time, when I met Duncan, he could barely speak. He was in a wheelchair and yet there was so much power between them. I discovered later that this happened to everybody, every reporter who met them. If you were doing a story about Byrne you put in something about Duncan, because whenever you were around them, you witnessed this chemistry they had and it was almost intoxicating. You couldn’t help but try and figure out what their secret was.

So I actually met Byrne through Duncan and started covering him and his struggle to try and get through the end of life with dignity. She was a large part of that. And then I discovered The Byrne Miller Dance Theater, and she’s bringing in these amazing modern dance companies to this little town. When I was a twenty-something transplant I thought there was nothing going on in town. And here comes Byrne and she’s bringing in Martha Graham, you know? It was an eye-opener.

MS: Obviously, you became very close. Did that evolve over time or did she “collect” you immediately?

TB: I realized pretty quickly that I was one of her collected daughters. I was not alone. There are many, many of us. And it felt great to be part of this community of people who were important to her. If she’d been a drug dealer I would’ve been out there selling drugs.

(Laughter)

MS: She might have been your Fagin.

TB: She was amazing. I found myself not having the appropriate journalistic objectivity when it came to her. And that was common. But eventually we got closer and closer and I got more involved in the dance theater. I was on her board for a while. Then when Duncan died we got even closer. At one point she had a blood clot in her leg and if she moved it could have been fatal. The doctors told me she couldn’t move. I thought they’re crazy. There’s no way a dancer can’t move and the only way this is going to work is if I’m her jailer/best friend. So I moved in with her.

There’s a neat part in the book about that, about this little dance we developed. I was so worried that she would forget about the blood clot and wake in the night and try and get up. I had to listen to the quality of her breathing and try and anticipate [her needs] and it became like a kind of dance.

MS: There are collected daughters and sons all over, some still in Beaufort, right?

TB: Many are still in Beaufort. I met them mostly when she turned 89. We had a big party and invited all of her collected children. It was amazing. They came from all over the country and it was as if we’d all known each other since birth. It was the craziest thing. One of them – my brother – is a Navajo elder who lives in Arizona. And you could tell with every one why she had picked them. We all had something in common. It was more than her, but through her.

I’ve kept in t ouch with them and I interviewed as many as I could for their recollections of Byrne. And it was funny, the stories we all remembered: how she and Duncan always held hands, how Duncan always told her she was beautiful and he watched her undress every day of their sixty years of marriage. These are the things she told all of us at various points in our lives. And we all remembered.

ouch with them and I interviewed as many as I could for their recollections of Byrne. And it was funny, the stories we all remembered: how she and Duncan always held hands, how Duncan always told her she was beautiful and he watched her undress every day of their sixty years of marriage. These are the things she told all of us at various points in our lives. And we all remembered.

Read Part Two of this Interview.

Read our review of ‘The Other Mother.’

GET MORE ONLINE:

www.teresabrucebooks.com

www.jogglingboardpress.com

www.garygeboyphotography.com

Follow Teresa’s blog at teresabrucebooks.wordpress.com