Chilled Big: How our hot film scene got iced and what can be done to thaw it out

“It wouldn’t be a movie made from my book, I can tell you that. It just wouldn’t be. Nothing any of these legislators can do will have as lasting an impact on tourism, on business – on anything else – than getting a movie made in South Carolina.”

– Author Pat Conroy on the possibility his books might not be filmed SC

The weekend prior to the opening of the fourth annual Beaufort International Film Festival, something akin to David’s slaying of Goliath happened in theaters around the country. A tiny, unheralded, poorly reviewed film adaptation of Nicholas Sparks’ novel, Dear John, knocked James Cameron’s behemoth sci-fi spectacle, Avatar, from atop the box office charts. Granted, Avatar’s race was almost run. The all-time top domestic and worldwide grosser was due to be toppled after dominating all comers for months and sucking up more than $700 million in domestic ticket sales. But Dear John’s opening triumph had a special resonance for anyone associated with the film industry in South Carolina. Shot back in 2008, Dear John is the last “big” movie to film in the state, making its title all the more ironic. And “big” is a relative term. The average budget for a major studio production is easily north of one hundred million dollars. Avatar is reported to have cost more than three times that amount. Dear John comes in at a relatively meager 25 million dollars, most of which was injected directly into South Carolina’s habitually anemic economy. Meanwhile our neighboring states continue to do big and bigger business with Hollywood. Dear John is both a reminder of how things used to be and a faint glimmer of hope for a return to those days – a very faint glimmer.

“This is an industry [in South Carolina] that is facing some tough headwinds,” says State Film Commissioner Jeff Monks. “When our incentives were reduced and our competitors’ incentives increased, South Carolina fell off the charts in Hollywood.”

There it is, the “I” word: incentives. Quite possibly the most important and pervasive term associated with modern American filmmaking apart from “CGI” and “directed by Steven Spielberg.” The concept is simple: offer television and film productions incentives in the form of tax rebates – a certain amount of cash back per dollar spent, often with a liberal cap on the total refund. I won’t bore you with the math. There’s plenty of it and it’s probably best explained by a tax attorney or anyone who’s ever cashed a production company paycheck. Often there are stipulations and codicils aimed to encourage hiring from within the indigenous talent pool – provided there actually is one. This too becomes a problem since the talent pool tends to go where the movies are actually being produced (which is not here). The bigger the incentive package, the bigger the project it attracts. It’s literally like fishing: the bigger the bait, the bigger the fish. Our neighbors are hooking marlin in deep water while we’re back at the pond with a cane poll and a can of worms.

In short, with our current incentives structure South Carolina is simply not in the hunt for the big fish. And at risk of running the analogy aground, this is pretty tough to swallow with so many trophies on the wall.

In short, with our current incentives structure South Carolina is simply not in the hunt for the big fish. And at risk of running the analogy aground, this is pretty tough to swallow with so many trophies on the wall.

What the hell happened?

“In 2006 the SC Department of commerce decided that our incentives were too aggressive,” explains Monks. “This is after they had just been passed and instituted and we recruited seven feature films, two television pilots and our first ever TV series.” Here’s where it gets weird. Essentially, the State Commerce Department, under brand new Sanford appointee and former Southland Log Home CEO, Joe E. Taylor, Jr. determined that the incentives were too lucrative. Department bloodhounds sniffed out a loophole in the legislation – legislation passed with the bi-partisan support of both houses – and dramatically slashed the entire program. A fairly competitive, across-the -board wage rebate of 20% was cut to 10% for non-state residents and capped at $3500 per person. At the same time more than a dozen other states either created brand new packages or boosted existing incentives as the competition for bigger more expensive projects heated up. In essence, the state changed the rules in the middle of the game. Literally overnight we yanked out the “Welcome” sign and planted “Keep Out!” in its place. This is almost literally like having the lottery folks roll up to your front door with a tractor trailer full of cash while you step out on the porch with a shotgun and yell, “Get off my lawn!” And they did. In the aftermath, the Commerce Department slogan “South Carolina means business” might as well include a parenthetical (Any business but the film business).

A nasty shock wave rippled through Hollywood. After decades of building South Carolina’s reputation as a prime feature film location brick by brick, the fiscal temblor that rumbled west out of Columbia reduced the walls of good intentions to a dust bowl of ill will. Anyone who deals with “The Industry” knows Hollywood’s like an elephant, it’s got a long memory.

The Competition

Robert Redford’s upcoming historical drama, The Conspirator, recently wrapped production after several months of shooting in and around Savannah. The Civil War era picture deals with the aftermath of the Lincoln assassination and the trial of Mary Surratt, the only woman charged in the conspiracy. Both Charleston and Beaufort were considered by the producers, if only briefly.

“Incentives were the deal breaker,” says Carlotta Ungaro, President of the Beaufort Regional Chamber of Commerce. “Deal breaker for us, deal maker for Georgia.”

“Incentives were the deal breaker,” says Carlotta Ungaro, President of the Beaufort Regional Chamber of Commerce. “Deal breaker for us, deal maker for Georgia.”

According to the Georgia Film Commission during fiscal year of 2008-2009 television and film projects dropped $641 million in the state with a total economic impact of $1.15 billion. And our neighbors to the south appreciate the importance of promoting their product. All a film or TV production has to do to raise the state’s flat 20% rebate to 30% is slap an official Georgia peach logo at the end of the credits. But Louisiana leads the pack with a base incentive package of 30%, with flexibility to boost that another 5%. The state film office website currently lists a jaw-dropping 63 feature films shooting over the past 15 months. Let’s not forget the 13 television series, as well, and all of this in a state with significantly less location diversity and infrastructure than South Carolina.

“Of all the industries out there, the film industry is the most sensitive to incentives,” says Ungaro. The Chamber also oversees the Beaufort Film Commission and is pushing for a more competitive incentive package. In other words, throw Hollywood a bone and as Ungaro points out, “Everybody’s throwing bones. If we want in we’ve got to play the incentives game.”

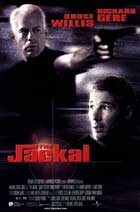

Movie money is easy money and a lot of it used to pump through this state in the form of blockbusters like The Prince of Tides, Die Hard With a Vengeance and Forrest Gump.

A big budget film means a massive and immediate cash flow into the local economy. Hotels are booked, restaurants and bars are filled, local suppliers watch sales spike. Jim Passanante was born into the business in Hollywood, but moved to the Lowcountry with the movie boom in the early ‘90’s. The scenic artist and set-builder has more than 70 feature films to his credit, including Gump, Big Fish and The Conspirator. For Passanante and his peers getting South Carolina back in the film business is a no-brainer. “I was the painter on Die Hard III,” he says. “I spent $350,000 dollars on paint. I had 52 people working for me. I had a payroll of about $165,000 a week. Plus all these people had per diems. So think of how much money was put back in the community.” The local paint store threw his crew a thank you barbecue when production wrapped. “They’d never had anybody spend that kind of money,” he recalls. “Get the tax incentives back and you’ll have more movies than you know what to do with.”

Besides the immediate local economic impact, there is the long term. The film and television business attracts all sorts of support businesses. Many of them are high tech and green. And then there’s the Forrest Gump Factor. Soon after that big budget movie spends millions o

Besides the immediate local economic impact, there is the long term. The film and television business attracts all sorts of support businesses. Many of them are high tech and green. And then there’s the Forrest Gump Factor. Soon after that big budget movie spends millions o f dollars and employees hundreds of people, it opens on thousands of screens across the country and the globe. “You’re marketed to the world,” says Ungaro.

f dollars and employees hundreds of people, it opens on thousands of screens across the country and the globe. “You’re marketed to the world,” says Ungaro.

It simply makes sense for a state dependent on tourism to pursue that kind of spotlight. That’s not going to happen until the attitudes and policies shift in Columbia, something Ungaro and others are urging local legislators to champion. “We are dependent on the policies of our state,” she explains, “because Beaufort’s not going to get a look if the [movies] are not looking at the state.”

Email Mark Shaffer at backyardtourist@gmail.com