By Margaret Evans, Editor

By Margaret Evans, Editor

In the preface to his Pulitzer and Tony winning play Doubt: A Parable, John Patrick Shanley wrote, “There is a symptom apparent in America right now. It’s evident in political talk shows, in entertainment coverage, in artistic criticism of every kind, in religious discussion. We are living in a courtroom culture. We were living in a celebrity culture, but that’s dead. Now we’re only interested in celebrities if they’re in court. We are living in a culture of extreme advocacy, of confrontation, of judgment, and of verdict. Discussion has given way to debate. Communication has become a contest of wills. Public talking has become obnoxious and insincere. Why? Maybe it’s because deep down under the chatter we have come to a place where we know that we don’t know… anything. But nobody’s willing to say that.”

While savoring these searing words last week, I couldn’t help pondering the fact that Shanley’s play was published in 2004, the same year Facebook was introduced to the world. Two years later, Twitter would make its debut, and the rest, as they say, is history. Fifteen years ago, Shanley was chiseling away at the tip of an iceberg. Today, his words feel even more relevant than they did then.

As I prepared to interview my friend Gail Westerfield about her role in Coastal Stage Productions’ upcoming production of Doubt, I decided to curl up one rainy holiday afternoon and watch the movie version, which I hadn’t seen since its premier in 2008. If you’ve never seen the play or the movie, here’s the official synopsis: “In this brilliant and powerful drama, Sister Aloysius, a Bronx Catholic school principal, takes matters into her own hands when she suspects the young Father Flynn of improper relations with one of the male students. The action takes place during the fall of 1964.”

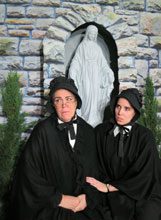

Gail has landed the role of Sister Aloysius, which earned Meryl Streep an Oscar nomination. You could call it the role of a lifetime. Gail’s director Luke Cleveland forbade her to re-watch the film – directors always want you to “make the character your own” – but she disobeyed him and has more than a few thoughts on the movie, the play, and all things Doubt…

Gail Westerfield: The film is quite different from the play, which is somewhat surprising given that Shanley wrote the screenplay anddirected it. As with all filmed plays, a lot of other locations and plenty of characters have been added in, and there are a few scenes that just aren’t in the play at all. The play only has four characters, so you never see the children in the school, for example; you only hear what the adults say about them, which is really effective, actually. All the scenes in the play take place in Sister Aloysius’ office, the garden, or the church, so it’s a very constricted world, which, again, I think is quite apt. There is plenty of dialogue in the film that is verbatim from the play, but there was also a lot that was missing, which in my opinion, made the story and the ideas less compelling and powerful than they are in the play.

Margaret Evans: In the movie, Sister Aloysius – played by Meryl Streep – is not particularly likable. She’s a conservative, authoritarian stickler for the “rules” – though we later learn that she’s not above breaking those rules in pursuit of what she deems to be “truth.” She’s often unpleasant and sometimes downright awful. But, as I watched the film the second time around, I found myself feeling a certain amount of sympathy, and even affection, for this character. I also kept thinking, “This woman is nothing like Gail.” How difficult has it been for you to “inhabit” this character (no pun intended)?

GW: Thank you for this question; it’s something I’ve thought about a lot and love to discuss! (Also, thank you for thinking I’m nothing like her. I love her, but she’s . . . flawed.) I hadn’t seen the movie since it came out, but I remembered thinking Streep’s character was much as you describe her – very pinch-faced, conservative, humorless, and a scold, which is putting it very charitably. She seemed mean and judgmental. Like you, when I watched it again, I appreciated her more, but I was blown away by how different Luke’s and my interpretations of the character are from Shanley’s and Streep’s!

There is so much fantastic stuff in the writing that tells you who Sister Aloysius is, how she sees herself, how others see her. There are also some clues in the script that aren’t overtly stated that have allowed me to make some fun choices. I am still evolving a biography of her, working on some ideas about what her life – and her faith – were like before she became a nun, what led her to make such a massive choice, why she chose the Sisters of Charity, as opposed to another order, and why rules and order – and their enforcement – mean so much to her.

I’m Meisner trained, not a Method actor, but it seems so key to do background research on the Church and priests’ and nuns’ roles in it, especially before the advent of Vatican 2. That’s been really helpful, and Julie Seibold, who’s playing Sister James, has a friend who’s a former nun who is coming to rehearsal to answer questions; Luke also has a friend who’s a priest, whom he’s been consulting to get details right.

Another thing I’ve found myself doing for the first time after decades of acting is thinking about a few people I know who have some of Sister Aloysius’ more “difficult” traits to help me understand, honor, and love those aspects of her.

When I was freaking out many years ago about playing a character that I had nothing in common with, who was strong-minded and wasn’t particularly charming or likable, my fantastic acting coach told me that I had to start by finding one trait in that character that I loved and one trait that she loved about herself. It wasn’t easy, but it made all the difference when I was able to do it, and since then, I have done that as a first step for every character I’ve played, especially the more problematic ones.

It’s such a great way to make a character that other characters see as almost two-dimensional into a fully fleshed-out, complex human. I’ve played Nurse Ratched in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest twice now, so finding the humanity and vulnerability and humor in Sister Aloysius is a comparative piece of cake! She’s definitely not an easy person to love or understand, but I love and understand her more every day.

ME: The film’s ending leaves the audience – or this member of it, anyway – in a great deal of “doubt.” We’re not exactly sure what we’ve just seen. We’re not sure what actually happened, and we’re not sure how we’d feel about what happened, even if we did know. We “doubt” not only our powers of perception, but even our own understanding of right and wrong, good and evil. This theme of “doubt” infuses the whole story, starting with the priest’s first sermon – about religious doubt – until the bitter end, when the ever-certain Aloysius seems to be questioning her own actions… and even her faith. The film really unsettled me; it left me with more questions than answers, in that rare way that only great art can.

GW: Exactly! That’s what’s so wonderful about the play and why it is “great art”: It assumes an emotional and spiritual intelligence in its audience, letting them consider all four characters’ words, actions, and perspectives, to come to their own conclusions, even if the conclusion is that they don’t know what to think and feel. It is so rich that I truly believe someone could come to all six performances and get more out of it each time.

Luke is planning to have talk-backs after each show, so audience members who want to discuss the play with the actors and each other can have that opportunity. I’m especially excited about this because it will be so cool to hear how people are affected by exactly what you experienced: that there are no easy answers here.

ME: All four of these characters seem to have different “takes” on Christianity – what it means and how it should be lived out. Does one of them speak for you?

GW:You ask the best questions! I was raised in the Disciples of Christ, mostly, though we went to a nearby Methodist church for many years of my youth because it was very close to home. Disciples of Christ is quite a liberal Christian faith, and our church, anyway, didn’t shy away from issues of social justice, so I really took to it in my later teens and 20s. I have a super-clear memory of telling my beloved minister at the time that I had a hard time reconciling my love of a liberal church – and my deeply held I-should’ve-been-a-hippie desire to have “church” out in a field of flowers – with my fascination with Catholicism, especially the incense and huge stained glass windows and the gold cups and icons and the Latin. The ceremony. My minister wasn’t surprised at all about this dichotomy. He said, “Well, of course. That’s theater.” Ha! He was so right, and I’d forgotten that, but it seems apt, though I don’t think it answers your question.

Years ago, I was working on ghostwriting a book for a priest (who unfortunately passed away before the project was completed) who fell in love and left the church to marry. He was a very energetic guy – in his 80s when we were working together – with a memory way better than mine, who’d been through so much of the Church’s 20thcentury history. He was as open-minded as this play’s Father Flynn, and as convinced of the need for the Church and its people to modernize as Flynn suggests – being friendlier, more of a family to parishioners – but he also understood why others objected to that and desired the authority, order, and mystery that, in Doubt, Sister Aloysius advocates, which, like so much, was changing in the ‘60s. I could go on and on about how the conversations I had with him have helped to shape my understanding of the period and of the roles priests and nuns had in the Church then and now.

ME: Is there any way in which you relate to Aloysius personally? As loathsome as she can be, it struck me that she is also a feminist of sorts – a strong woman going up against the patriarchy of the Catholic Church, and actually getting things done. Also, it seems she truly believes she’s protecting a child, and she’s fierce about it.

GW: Absolutely. I completely agree. I actually think her issues with the church hierarchy are a lot clearer in the play than they are in the movie. She’d sooner die than think of herself as a feminist, but she totally is. She doesn’t necessarily question the inherent patriarchy of the Church, but she observes pretty early on the gulf that exists between the convent and the rectory.

I keep using the term “avenging angel” for her, and that’s one of the things I relate to in her character, because I believe her ferocity in protecting children is not because she hates men or the patriarchy, certainly not the Church itself, but because she sees they need protection. She is certain she knows a predator when she sees one, and she’s savvy enough to know that she can’t follow the rules to stop him because other men wrote those rules, so he will not be stopped.

Aloysius is fiercely intelligent, but she also is full of feeling that she doesn’t allow herself to express to others. This is so fun to play with, as is playing someone with such strong convictions about everything. I relate to that, and have experienced the scorn of people who see that as rigidity, “intolerance” as Father Flynn calls it. It’s fascinating to me to see how all of this holds her up – until it doesn’t anymore.

ME: Tell me a little about your cast mates and director.

GW: Right from the beginning, it has been a blast to act with these wonderful, generous actors: sweet Julie Siebold, whom I’ve mentioned; Brooke Pearson, who is an incredible Father Flynn, and Paulette Edwards, who was simply born to play Mrs. Muller; I’ve literally gotten goose bumps ever time we do her scene, including twice in auditions! We all have great chemistry, and we trust each other, which is essential to make telling a story like this successful. Luke Cleveland, our director, is extremely generous. He’s also passionate, energetic, and very imaginative. He has given me some great ideas, and he’s very much about collaboration with and among the cast.

ME: Here’s your chance to really sell it, Gail! Why should people come see this show?

GW: Because it’s a drama and concerns the Catholic Church, I think some people might shy away from it, so I appreciate the chance to tell them that it will be a wonderful, thought-provoking, but also funny evening. The play is relatively short, and the production will be fast-paced, so it’s not an endless, talky drag by any means.

For some time, there has been a shortage around here of live dramatic theater, so I demand (a la Sister A.) that all the people who have been telling me for the last 5½ years that they want to see that show up at AMVETS for Doubt! I would also love to see younger people there, who maybe haven’t gotten to see a lot of quality drama on stage. As someone who grew up only seeing musicals – and some very good ones – I found my first times seeing – and then being in – “straight” shows to be unforgettable. I still think there’s nothing like the charge of energy you get from live theater, whether you’re on the stage or in the audience.

I have no “doubt” that this play will inspire conversation, but I also believe it might make some want to get involved with this art form.

ME: And I have no “doubt” we theatre lovers are in for a profound treat. Thanks, Gail, and break a leg.

Doubt: A Parable opens Friday, January 24thand runs for two weekends at the AMVETs in Port Royal. For tickets, call 843-717-2175 or visit www.coastalstageproductions.com

Above: Gail Westerfield (left) and Julie Seibold in ‘Doubt’