By Margaret Evans, Editor

My advance copy of Our Prince of Scribes: Writers Remember Pat Conroy had been languishing on my bedside table for weeks. I couldn’t bring myself to pick it up.

There were reasons for my reticence. For one, my beloved friend, mentor, and sometime-employer had been gone for almost two and ½ years now, and I was loath to rekindle the grief that had been such a long time leaving.

But to be brutally honest – and Pat demanded nothing less than brutal honesty – there was something else going on, too, I think. Something ugly that felt like… insecurity? Possessiveness? Jealousy?

There was some nasty, wormy creature burrowed in my soul that dreaded an encounter with a host of other writers waxing eloquent about my Pat Conroy – many of them better writers than I am, who knew him better than I did, and surely had memorialized him better than I had. The thought of it stung. How could I compete with all those real writers – Josephine Humphreys and Mary Hood, Rick Bragg and Ron Rash! – not to mention all those Hollywood celebrities (Barbra Streisand and Michael O’Keefe!) and especially all Pat’s true friends, the ones who’d really known him? I wanted to be generous and large of heart – it’s the Conroy way – but the nasty, wormy creature was coiled up and hissing.

Pat used to say (only half joking) that writers are the biggest a$$holes in the world – himself included – and here I was, living proof of that maxim. The realization shamed me even as it tickled me, so I finally sucked it up, rose above the worm, and reached for the book, which was now practically glowering at me from my nightstand.

And the moment I started reading, I remembered. I remembered the truth I’d temporarily forgotten in my anxiety – that there’s enough Pat Conroy to go around. There always was and there always will be. His was not a stingy love, doled out in skimpy bits to only those who earned it – or those in his inner circle, or his circle of fame and accomplishment. He was far more lavish and indiscriminate with his affections. Pat was a bottomless pit of love, an overflowing fountain of love, and those who got close, even if only through his books, typically felt our hearts expand to receive that love. And we became better for it.

How much Conroy Love you got was limited only by your capacity to receive it. He was always giving; it was simply a matter of taking. And the truth is, I wasn’t always up to the  task.

task.

I have a fundamental flaw – I’ve always known it – that makes it hard to fully grasp the hand of friendship when it’s offered. There’s something in me that struggles with the vulnerability required of authentic friendship. I lack the courage to be truly seen and known, because if anybody truly saw me and knew me – in all my deep, dark ugliness – they couldn’t possibly like me. Or so I tell myself. So eager am I to be liked that I regularly sabotage my chances of being loved, for such intimate exposure is the stuff of real friendship. The stuff of love.

Of course, Conroy knew all that about me. We never spoke of it, but the man saw right through me, and I knew it. He often chided me for things like being too nice, or playing it too safe, or not putting myself out there. Though I never told him, he knew I feared failure as much as I feared friendship. Pat Conroy had ambitions for me, and I disappointed him regularly by neglecting to pursue them. Time after time, he threw me the ball and I dropped it.

“Kid, I want you to gather up a bunch of your best interviews and send them off to Southern Living and Garden & Gun,” he’d say. “I’ll write you a letter to go with them.” (I never did.) “Kid, you do something few writers can do; you create a whole world in a column,” he’d encourage me. “You need to publish a collection of your best. I’ll write the foreword.” (I still haven’t, and now he never will.)

I got my first editing gig, in the early 90s, thanks to an interview Pat graciously gave me when I was a 20-something-year-old shop girl and his neighbor on Fripp Island. The publishers of the now defunct Beaufort Magazine were so impressed with that interview – or, more likely, my acquaintance with the already iconic Conroy – that they hired me to edit their magazine fulltime, a job I enjoyed till the publication folded six years later.

Over the 25 years I knew Pat Conroy, he was always reaching out to me, giving me one opportunity after another to raise my game, to be more than I was. I still can’t figure out why, exactly, except that for some inexplicable reason, he loved me – love was just what he did – and he knew how I was. He knew I’d never ask him for help, that I would never “impose” on my celebrity friend – or anybody else – because I was a “nice Alabama girl” who didn’t believe in herself. It drove him nuts, but he got it. And he never gave up on me. Three years before he died, he reached out – again – and hired me as his editorial assistant at Story River Books, the publishing imprint he started for the sheer love of writers (those a$$holes!) and readers. “Kid, I’m training you to take over the Beaufort office,” he said, “so I can get back to novel-writing.” We had some wonderful times working together on that project, but all too soon, he was gone. His novel was left unfinished, Story River closed up shop, and the “Beaufort office” never came to be.

There were sometimes long stretches of silence between us – years, even – but he would always pull me back into his charmed circle. (Pat was a big believer in circles, and once you were in his orbit, you’d always come back around.) Nine years ago, he called me out of the blue – we hadn’t talked in ages – saying he wanted me to have the “first interview” upon the publication of his novel South of Broad. He dropped off an advance copy at my office and I took it with me on a family trip to San Francisco, my husband’s hometown. I vividly remember sitting in our hotel bed, reading that sprawling behemoth of a novel – part of which, ironically, is set in San Francisco – and bursting into tears when I came to the surprise cameo appearance of a character – a young Charleston Post & Courier reporter – by the name of Amelia Evans.

That’s my daughter’s name.

Pat Conroy was always doing stuff like that for the (many, many) people he loved. Even those of us, like me, who didn’t deserve it . . . who weren’t large enough of spirit, who didn’t love ourselves enough, to fully receive his enormous love, or properly return it. You didn’t have to earn Pat Conroy’s love. It was unconditional and it was inexhaustible.

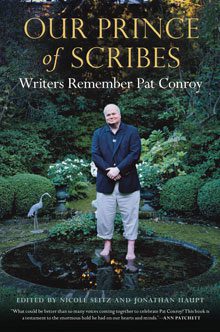

And this is the beautiful truth that blooms again and again – in 67 marvelously varied flowers – as you read Our Prince of Scribes: Writers Remember Pat Conroy. Not that Pat Conroy was a saint – he wasn’t – but that he was a man whose capacity to love was almost other-worldly. In these essays, you’ll meet a man who was troubled, tormented, angry, scathing, outrageous, hilarious, tender, noble, brave, and generous beyond measure. But most of all, you’ll meet a man who damn-well knew how to love.

And thanks to the devoted efforts of co-editors Jonathan Haupt and Nicole Seitz, and the work of 67 very fine writers, his legion of fans will come to love Pat Conroy even more than they already do.

The Pat Conroy Literary Center will host a book launch event for Our Prince of Scribes at Bluffton’s historic Rose Hill Mansion from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. on September 18. To reserve your ticket, visit https://rosehill-scribes.bpt.me by September 15. For more information, visit www.patconroyliterarycenter.org