Part 6: Did America Really Start Here?

Dr. Rowland made a rather extreme statement. He said, “America started here –not in Jamestown, Plymouth Rock, or St. Augustine.” If America really began “here,” we will have certainly identified a gigantic asset for not just South Carolina . . . but for our country. But can we prove that America began here . . . in Beaufort County? In South Carolina? I believe the answer is “yes.”

You and I first formed our ideas about where America began in the classroom. Later on we were influenced by the promotional material that was distributed by Jamestown, Plymouth, MA and St. Augustine’s Chamber of Commerce. I took the time to review several of the American history textbooks that our 7th and 8th grade students read. To generalize, this is what they say:

“The Spanish were the first to send a number of explorers to America. They failed at trying to establish settlements. The first major settlement was an English settlement at Jamestown in 1607. The second major settlement was at Plymouth, MA, in 1620. That is where the Pilgrims landed. The Spanish did establish a secondary settlement at St. Augustine. It is the nation’s oldest continuously existing city.”

This may sound correct. But it is not. When I started to dig into this issue, Larry Rowland suggested that I first understand the economic and political situation that the three major European powers were in at the time. He said with firmness in his voice, “When you understand how France, Spain, and England were relating to each other in Europe, you will then understand how they entered America.” It made sense. So I went back to school. This is what I learned. This was Europe around the mid-1500. When Spain’s King Charles V died he left his son, Philip II, with an empire that included Spain, the Spanish Netherlands, Naples and the American colonies. Spain’s economy, however, was based on conquering territory and extracting valuable assets . . . like gold from Peru and silver from Mexico. Spain was not a trading country. It relied on the Dutch in their Netherland’s “colony” to do their trading. One would think that with the 339,000 pounds of gold that Spain had extracted from Central American mines that Spain would be wealthy. It wasn’t. It was on the edge of bankruptcy. Spain was spending more than it took in. While it was extracting gold and silver in Central America, it was plagued with a protestant rebellion in the Netherlands and a war with the Turks in Italy. Meanwhile, English and French privateers (i.e. commerce raiders) were attacking its ships in the Caribbean. Spain also saw itself as the standard bearer for Catholicism. And, as the Spanish Inquisition showed, it was willing to use a firm hand against any country that gave any support to Protestants.

This was Europe around the mid-1500. When Spain’s King Charles V died he left his son, Philip II, with an empire that included Spain, the Spanish Netherlands, Naples and the American colonies. Spain’s economy, however, was based on conquering territory and extracting valuable assets . . . like gold from Peru and silver from Mexico. Spain was not a trading country. It relied on the Dutch in their Netherland’s “colony” to do their trading. One would think that with the 339,000 pounds of gold that Spain had extracted from Central American mines that Spain would be wealthy. It wasn’t. It was on the edge of bankruptcy. Spain was spending more than it took in. While it was extracting gold and silver in Central America, it was plagued with a protestant rebellion in the Netherlands and a war with the Turks in Italy. Meanwhile, English and French privateers (i.e. commerce raiders) were attacking its ships in the Caribbean. Spain also saw itself as the standard bearer for Catholicism. And, as the Spanish Inquisition showed, it was willing to use a firm hand against any country that gave any support to Protestants.

Spain believed that it had a good reason to be the world zealot for Catholicism. In 1494, the Spanish Pope, Alexander VI, issued a degree  which gave all unclaimed world lands to either Portugal or Spain. The Treaty of Tordesillas split the “New World” between Spain and Portugal. The line of demarcation gave most of North and South America to Spain. Brazil was given to Portugal. In King Phillip’s eyes, America was his. King Philip only had one problem. The French and English did not agree.

which gave all unclaimed world lands to either Portugal or Spain. The Treaty of Tordesillas split the “New World” between Spain and Portugal. The line of demarcation gave most of North and South America to Spain. Brazil was given to Portugal. In King Phillip’s eyes, America was his. King Philip only had one problem. The French and English did not agree.

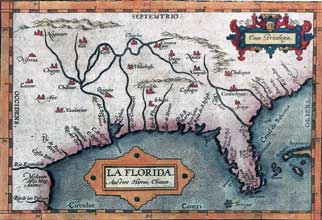

La Florida stretched from the Keys to France’s Newfoundland. And it stretched from the Atlantic to the Mississippi River. Remember, in 1492 no one knew what land existed west of the Mississippi River. La Florida included half of today’s United States. This is an early view of the map.

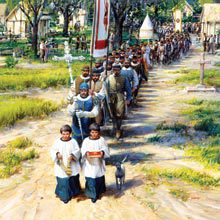

The only problem was that the other major European countries did not accept the Pope’s mandate. Spain also had an emotional tie with the unsettled America. In 1526, Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon, a wealthy Spanish lawyer from the colonial capital of Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), tried to establish a settlement in South Carolina. He called it San Miguel de Gualdape. It failed after a few months. In 1528 Panfilo de Narvaez landed at Tampa Bay with 400 men. It failed. Hernando de Soto landed near Tampa Bay in 1539 with 600 men and ten ships. He wandered for three years through the Southeast. Then, in 1559 Tristan de Luna led 1,500 soldiers and settlers to Pensacola Bay. A storm demolished his fleet. Spain paid a big price for these “probes.” In the mind of King Philip II, he already owned America. It was just a matter of when he could afford to mine his claim.