PART 10: The Struggle to Survive

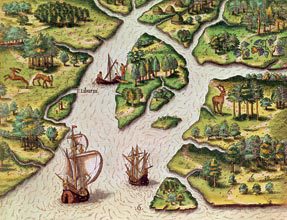

As soon as Menendez destroyed the French settlement near Jacksonville, he headed to Port Royal Sound to build a military outpost at Santa Elena. However, by 1569, Santa Elena was a true settlement. It mirrored a typical town in continental Spain. The town included every trade that one would find in Spain. It had a tailor, blacksmith, carpenters, cooks, a tavern owner, a pottery maker, money lenders, traders, farmers, priests, and soldiers. The town operated within a social hierarchy the same as in post-medieval Spain.

As soon as Menendez destroyed the French settlement near Jacksonville, he headed to Port Royal Sound to build a military outpost at Santa Elena. However, by 1569, Santa Elena was a true settlement. It mirrored a typical town in continental Spain. The town included every trade that one would find in Spain. It had a tailor, blacksmith, carpenters, cooks, a tavern owner, a pottery maker, money lenders, traders, farmers, priests, and soldiers. The town operated within a social hierarchy the same as in post-medieval Spain.

There were commoners (the troops, servants, farmers, fishermen, and day laborers). There was also  an evolving middle class (the master craftsmen; the professionals and merchants). And there was the nobility – the leaders of the civil government and the commanders of the Fort.

an evolving middle class (the master craftsmen; the professionals and merchants). And there was the nobility – the leaders of the civil government and the commanders of the Fort.

The living conditions were similar to that of a Spanish town. A commoner’s house was small. It had one room with one window. The walls were made with daub, a kind of mud plaster that surrounded small vertical branches. The roofs were covered with thatch, just as they were in Spain.

The typical family would own one bed, one trunk, a table, a few chairs, and some kitchen utensils. That is it. Their home would be on a 50′ X 100′ lot. The nobles lived on a 100′ X 200′ lot. To give you an idea of the difference in living conditions: Pedro Menendez and his wife moved into their Santa Elena home in July, 1571. The household goods that their servants unpacked included embossed leather wall hangings, beds with scarlet fringed canopies and lace and carmine taffeta coverlets. They also unpacked fine bed and table linens, carpets, a red satin bed, seven saddles and their tack. They also had to find room for a pewter service for 36, candlesticks, a silver ewer, kitchenware, and a keg of flaxseed and hempseed.

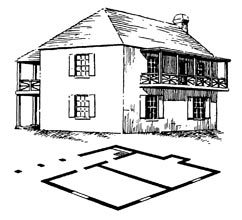

The late Albert Manucy projected what kind of house a noble would have built on Santa Elena or St. Augustine in 1571. (See left.) This is a description of the plot plan and the house’s features: “The plot plan would show a two story home. It would have two large storerooms on the first floor and stairs to the second floor. The second floor would include a kitchen, two or three bedrooms, and a living/dining room. A second floor balcony would be attached to one side of the second floor. The house would open directly to the street. The lot would be totally fenced. Behind the house would be an arbor, a well and flower garden. There would also be an outside kitchen, kitchen hearth and vegetable garden with a corn crib. A chicken roost would be near the outside kitchen. The lot might also include a smokehouse behind the house. Inside the fenced lot would also be a corral with a well and a stable for horses.”

The late Albert Manucy projected what kind of house a noble would have built on Santa Elena or St. Augustine in 1571. (See left.) This is a description of the plot plan and the house’s features: “The plot plan would show a two story home. It would have two large storerooms on the first floor and stairs to the second floor. The second floor would include a kitchen, two or three bedrooms, and a living/dining room. A second floor balcony would be attached to one side of the second floor. The house would open directly to the street. The lot would be totally fenced. Behind the house would be an arbor, a well and flower garden. There would also be an outside kitchen, kitchen hearth and vegetable garden with a corn crib. A chicken roost would be near the outside kitchen. The lot might also include a smokehouse behind the house. Inside the fenced lot would also be a corral with a well and a stable for horses.”

Before Santa Elena could fulfill any of its goals to expand, it had to survive. Santa Elena residents faced the same problem that later existed in St. Augustine and Jamestown. They had to have a continuous supply of food . . . just to survive. However, the first troops and settlers looked upon Santa Elena as if it were Spain. They did not have the advantage of knowing what prior settlers had grown on our sandy shores. So, they brought with them barley and wheat seeds and grapevines. They quickly withered. They also unloaded the types of animals that thrived in Spain – cows, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens. The native bears and “wild cats” ate most of those animals. The pigs survived, but only because they went into the woods. Santa Elena, like St. Augustine, Jamestown, and Plymouth, had to rely on one source to keep them alive – the local Indians. They knew what grew in the Lowcountry. It was corn, melons and squash. It was also fish, crabs, oysters, wild turkey, and deer.

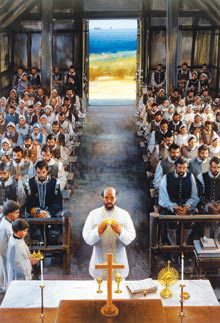

Governor Menendez had a ‘John Wayne’ persona. He was a swashbuckling explorer, a risk taking entrepreneur, and a businessman. He had strong leadership skills. When he met with the leaders of the Native Americans along the coast, they immediately respected him. Pedro Menendez treated the Indians with respect and honored most of their traditions. But that was not the case for others in his command. Spain’s culture worked against their very survival. By Spanish tradition, people were largely placed into two groups: nobles or commoners. There was an evolving middle class of professionals. But it was small. Thus, the Santa Elena troops, who were not well trained, approached the native Americans as if they were serfs. Their message was, “We will give you protection if you agree to convert to Catholicism and pay us a continuing tribute.” That tribute would either be food, goods, or service. Initially, the tribes would agree. But as the settlers became hungry, they demanded food or just stole it. That angered the Indians to the point that it was not safe for the settlers to go to the water to fish.

The flash point was 1576 when the Indians burned the entire town. The town settlers immediately moved to St. Augustine. And St. Augustine became the new capital of La Florida after 1576. The Spanish rebuilt Santa Elena the next year –1577. This time they covered some of the roofs with lime-based cement. Now it would be more difficult for the Indians to set Santa Elena on fire. It was still destined to be a major settlement for the next ten years.

Admiral Menendez saw England as their most feared enemy. The English had already made probes in the mid-Atlantic and New England coastline. Moreover, they had the Navy and the bank account to mount a serious attack on La Florida. In June of 1586, England’s Sir Francis Drake took a fleet of ships and scourged the Spanish Caribbean and sacked Santo Domingo and Cartagena.

St. Augustine was next. Drake burned St. Augustine in early June and headed for Santa Elena. But the admiral mistakenly overshot Santa Elena. Still, this raid showcased England’s sea power. Spain immediately issued orders to consolidate Santa Elena into St. Augustine. It no longer had the resources to protect both settlements.

What did Santa Elena look like at the time? Chester DePratter, Director of Research for the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, told us that they have only uncovered 2- 4% of Santa Elena. Thus, the archaeologists have only pinpointed several forts, the town plaza, and a few other buildings.

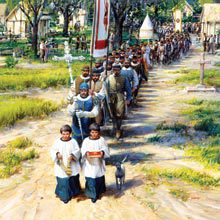

The town had three dominant structures: the church; the fort; and the town plaza. The National Geographic Magazine printed an article in 1988, with a picture (left) that showed how the church might have looked.

The town had three dominant structures: the church; the fort; and the town plaza. The National Geographic Magazine printed an article in 1988, with a picture (left) that showed how the church might have looked.

The town was laid out exactly as they would plot a town in continental Spain. What is amazing is that this 16th century town is now six inches under the ground on Parris Island. Furthermore, it is considered the most pristine and untouched Colonial Spanish archaeology site in America. Tim Herrington is the head of cultural and natural resources on Parris Island. Dr. Stephen Wise is the base’s museum curator and cultural manager. In my opinion, the preservation of Santa Elena is largely due to their diligence, and that of their archaeologist, Kim Zawacki.