The quintessential Lowcountry artist talks about his life, his work, the future of art without public funding, the culture of rice, copycats, and the joy of coming home.

When Jonathan Green came into the world, he brought with him an inescapable sign of his specialness. He was born wearing a caul, an inner fetal membrane that covered his head at birth. In some societies, this is interpreted as a token of great luck or that this child will never know death by drowning. But in the Gullah society along the South Carolina coast, it insures that the child is touched by an uncommonness and magic that will bring inordinate grace to the community. From the beginning, Jonathan Green was marked and grew up known as “the child of the veil.” – Pat Conroy

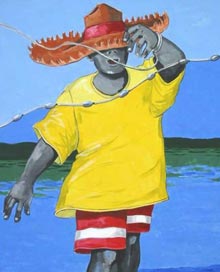

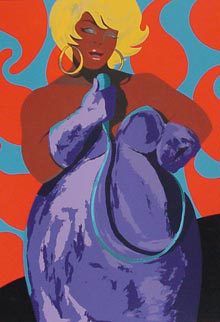

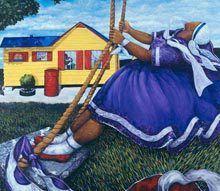

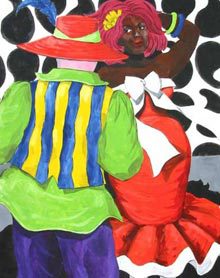

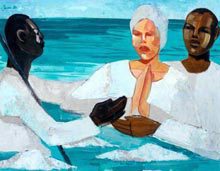

I’d heard he was “enigmatic.” This made me nervous. Much like the figures in his iconic paintings – most of whom look away from the viewer, lost in concentration or some sacred reverie – I feared he might be private… reserved… a little standoffish. What I encountered, instead, was a man just as warm and welcoming as the exuberant, sun-drenched landscapes those cryptic figures inhabit.

What can I tell you about Jonathan Green that you don’t already know? With the possible exception  of writer Pat Conroy, no living artist has done so much to capture the world’s imagination and focus it squarely – longingly – on the South Carolina Lowcountry. His career has been one long series of bright, beautiful postcards from his native land. “Wish you were here,” they whispered and sang… even though the artist, himself, was not.

of writer Pat Conroy, no living artist has done so much to capture the world’s imagination and focus it squarely – longingly – on the South Carolina Lowcountry. His career has been one long series of bright, beautiful postcards from his native land. “Wish you were here,” they whispered and sang… even though the artist, himself, was not.

Now, more than 35 years after leaving this place with which his name is practically synonymous – first for Chicago, then Naples, FL – Jonathan Green has come home. He spoke to me by telephone from his new studio in Charleston…

Margaret Evans: Jonathan, what possessed you to leave Naples after 25 years and return to the Lowcountry?

Jonathan Green: Well, so much of my work has always been here in Charleston. Exhibitions, public speaking engagements… so much of it was here. The travel expenses were adding up, and frankly, the recent economy has been terrible for artists. So, I figured this would be a great opportunity to slightly alter my lifestyle. I would be closer to my work, closer to my subject, and more important, closer to most of my relatives. Many of my people are getting older and even dying… This just seemed like a perfect opportunity at a perfect time.

ME: You’ve said that 95% of your relatives are still in the little town of Gardens Corner, where you grew up. It’s not too far from Charleston. Do you make it over there very often?

JG: (Laughs) I’m in church every other Sunday serving as an usher.

ME: They must love having a famous artist in the congregation…

JG: Well, I don’t know about that. (Laughs) They love having me, I guess. The people at my church see me as the person they knew as a baby and watched grow up… someone who moved away, but who has continued to participate in the community, and give back to the community, over a lifetime… who has remained close to his mother and the rest of his family… That’s who I am to them. A “famous artist” means very little to them compared to Jonathan Green, the child they knew… the child who grew up with the veil.

ME: So it’s been a good move, then? You’re glad you did it?

JG: Ecstatic. It’s been natural and easy. And you know, I’m just so fortunate that I had a place to come back to. Most people, once they’ve left home, find it very difficult to return. I think Thomas Wolfe talks about this, doesn’t he? (Laughs) You know, I read that a long time ago, and I refused to believe that from him… All of my career as an artist, I just refused to believe that you can’t go home again.

ME: Well, some would say you never really left, judging by your work. And now, with this move, you’ve decisively proved Wolfe wrong! Sounds like it’s been good on a personal level. How about business-wise? I’d guess Charleston is a pretty good location for Jonathan Green, the artist.

JG: A great location. And since moving back here, I’ve started something new. I’m now doing works on paper, which are only a fraction of the cost to create. This has helped to spur a whole new generation of collectors.

ME: Speaking of a whole new generation… lots of people are worried, right now, about the future of the arts – not just in South Carolina, but across the country. The U.S. House of Representatives is looking to make deep cuts to the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA); and closer to home, our new governor, Nikki Haley, has proposed doing away with the SC Arts Commission. At the risk of asking an all-too-obvious question… do you think this is a bad idea?

JG: (Laughs) Of course it’s a bad idea! But you know what? It’s also a wonderful opportunity. It’s an opportunity for us as a community – as educators, as supporters – to realize that until we, as individuals, support our own arts, then we cannot propose a culture. We cannot talk about a culture. If people are not supporting the arts, then they don’t really care about the culture. Until there are art classes at every level of school, churches collecting art, various institutions collecting art – fraternities, sororities, clubs, corporations, you name it – then we simply can’t propose a culture. Everybody should be supporting the arts.

ME: So, not just the government? Is that what you’re saying?

the government? Is that what you’re saying?

JG: Everybody. This is kind of a wake-up call, I think. I’m actually excited – quietly – that they’re proposing to take [state and federal funding] away. Because it’s going to wake people up! All people. You know who should be the main supporters of the arts? Grandparents. They’ve lived long enough, they’ve seen enough, and they know art works. It’s an integral part of a child’s development.

ME: You do a lot of work with children. Do you see education as an important part of your role as an artist?

JG: I think the goal of artists is to educate all people. I’m particularly interested in children because I’m a believer that art should be part of every aspect of a child’s development. What’s the first thing a young child does? He picks up something to make marks on. That’s an early form of self-expression. When a child is in trouble, what’s the first thing the police department psychologists do? They get the child to look at and draw pictures.

ME: And studies have shown that training in the arts improves student performance in academics, right?

JG: In everything! Absolutely. It’s like this: Say you have a blueprint for life. If you removed 40 % of the image of the blueprint, it would be pretty difficult to follow. When you remove the arts from the lives of people, it makes them very difficult to draw into a community and a culture.

When we reach the age of maturing and changing and developing, we need the arts in our lives to help us express and process that change. Look at many of the kids today who are disturbed or troubled… You’ll find they don’t have any arts. They don’t have a culture. All over the world we have festivals, symposia, seminars, about moving from childhood into adulthood via dance, music, visual performance, body paint … expression. But in so much of our modern American culture, we don’t have any of that; so the kids don’t know what to do when they reach the age of 10 or 11. They don’t know how to express themselves, how to decorate or adorn themselves for specific rites or festivities. It creates this major void their lives, and they really don’t know what to do with themselves for about five years.

know how to express themselves, how to decorate or adorn themselves for specific rites or festivities. It creates this major void their lives, and they really don’t know what to do with themselves for about five years.

ME: It seems to me that ignoring arts education is like teaching to only half the child. You’re ignoring a big part of the human brain… the whole right side, really.

JG: You’re exactly right.

ME: My daughter is a 4th grader at Lady’s Island Elementary. You came to visit her school last year, and spent a great deal of time with the kids. When I told Amelia I was interviewing you today, she was over the moon. She fancies herself quite the little expert, too. She said, “Mom, don’t be nervous. He’s really, really nice.”

JG: (Laughs) I’m their hero, because they know I’m giving them something they can enjoy, appreciate, and live by forever. And with this gift of art, they can influence other people, too.

ME: You are their hero, Jonathan, I can tell you that. Lady’s Island is the arts-integrated elementary school here in Beaufort. My daughter has extensive classes in visual arts, music, drama and dance several times a week, along with all her academics. I could not be happier to see the kind of bright, well-adjusted kids that are coming out of this school.

JG: They’re going to be great people! And they’re going to change the culture and community where they came from.

ME: Shifting gears a bit… Here in the Lowcountry, it’s impossible to turn around without seeing artwork that’s been influenced – sometimes quite heavily – by Jonathan Green. How do you feel about that?

JG: I love it! I copied when I was young, and a student, and I know that it’s through the copying, through the mimi cking of other artists, that you learn about the materials of art. Not only that – you learn other ways of expressing imagery that speaks to your culture. If I’m a vehicle for more people to become immersed in art, then that’s a wonderful position to be in!

cking of other artists, that you learn about the materials of art. Not only that – you learn other ways of expressing imagery that speaks to your culture. If I’m a vehicle for more people to become immersed in art, then that’s a wonderful position to be in!

ME: What a generous response. You know, you’ve got quite a few adult “copycats” too – not just students – and some of them seem to be doing pretty well.

JG: (Laughs) Some of them are doing better than I am!

ME: I don’t know about that, but they seem to be having a good deal of success painting in the style you popularized. To be fair, they all have their own variations on the theme…

JG: Sure they do! That’s part of making the art your own. They’re not taking anything from me, really… they’re just borrowing. I’m flattered.

ME: You’re also very gracious. And you’re bringing that gracious spirit here to Beaufort on Friday, March 4th, as an honored guest and speaker at the USCB Center for the Arts. What will be the focus of your lecture?

JG: I’ll be talking about my life as an artist coming out of the rice culture. My ancestors planted rice as late as, say… well, my great aunt, Emily Albergotti. That was as recent as 1960. As a child, I got to see the fields… got to see people winnowing the rice….

ME: And you’ve launched something called the Lowcountry Rice Project. Can you tell me a little about it?

JG: Well, it’s an educational effort. I’m working with a group of organizations, including USC, the College of Charleston, Penn Center, the Charleston Public Library, and several other major entities that deal in history and culture. We created this project around rice, in part, so that we could use “RICE” as an acronym for Race & Culture. But also, because it’s just a very natural connection.

Rather than talking about enslaved Africans being slaves, we want to focus on their incredible contribution to the rice economy, which lasted well over 200 years. It literally built the Southeast. We want to look at all that it took to prepare the rice fields: Moving hundreds of cypress logs, 10 to 15 feet in diameter, creating the dykes, the infrastructure… Who were these people who made this possible? Where did they come from? How was it that Europeans knew about them, specifically? And why did they export well over 10 million Africans to North America? With the Lowcountry Rice Project, we hope to educate people about this shared heritage of ours… to create a platform for honest, informative discussions around the culture of rice.

ME: As I listen to you, Jonathan, the two words that keep coming up are “education” and “culture.” I know you see yourself as an educator. But you also see yourself as a keeper of the culture, don’t you? And specifically, the Gullah culture… a culture that’s otherwise slipping away?

JG: Absolutely. And really, that’s my job. That’s what I’ve done all my life, and will continue to do for the rest of my life.

ME: We’re all very excited that you’ll be here for “Celebrate the Arts.” It’s the first community-wide Arts Festival to be hosted by USCB since it committed to an emphasis on the visual arts here at the historic Beaufort campus back in 2009. The university has also just created the Center for the Arts, and is producing some wonderful theater productions. What do you say to all of the above?

JG: Glorious! Wonderful! Perfect!

ME: Just like this conversation. Thank you so much, Jonathan. I look forward to seeing you March 4th at USCB.

Read more about “Celebrate the Arts” at USCB.

Read more about Jonathan Green.