Ride Along on an Epic Quest in Teresa Bruce’s Memoir The Drive

Ride Along on an Epic Quest in Teresa Bruce’s Memoir The Drive

Interview by Mark Shaffer

Photographs by Gary Geboy

“We will follow my father’s route into the Peruvian highlands, through the looking glass of the girl I once was. I am ready. I have maps. I am prepared. But it will not matter. Whatever will happen next will do so without any regard for my plan or purpose.” – Teresa Bruce, The Drive

Tragedy is a sneak thief in the night; an unannounced, unexpected intruder who takes the thing most precious to you without reason or explanation and vanishes amid the wailing. Or so it seems.

But tragedy never leaves of its own accord. There comes a time when you either set it a permanent place at the table or drop it at the bus station with a one-way ticket out of your life. In 2003 Teresa Bruce packed hers up in a camper along with her new husband, old dog and a contraband pistol and drove it to Bolivia.

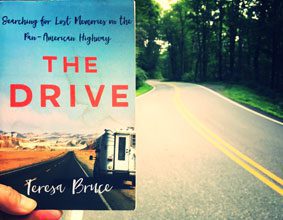

It was the second trip down the Pan American Highway for the author. Thirty years earlier, in the aftermath of her baby brother John John’s death in a freak accident, her father loaded his wife and two small daughters into a behemoth of a homemade camper trailer and fled Oregon for the tip of South America and ultimately, South Africa. I’ve heard bits of t his tale for years, usually in the roseate glow of a Pigeon Point sunset sipping tequila. But the scope and magnitude of those journeys somehow evaded me until they all came together in her new memoir, The Drive: Searching for Lost Memories on the Pan American Highway.

his tale for years, usually in the roseate glow of a Pigeon Point sunset sipping tequila. But the scope and magnitude of those journeys somehow evaded me until they all came together in her new memoir, The Drive: Searching for Lost Memories on the Pan American Highway.

In 2003 Gary Geboy and Teresa Bruce were newlyweds living successful jet-set lives in Washington, DC. He was a cinematographer and she was a Vice President at a global public relations firm. They often worked and traveled together and owned a house on Capitol Hill. And they chucked it all for a Ford F-350 topped with a retrofitted vintage camper and a mission to find the remnants of her childhood, still locked in her father’s cobbled-together camper somewhere in the wilds of Bolivia.

***

Teresa Bruce: This sounds weird, but it wasn’t even my idea. It was Gary’s when I introduced him to my parents and he heard about the first trip. That childhood trip for us was the story of our family. I call it the slide show version of our history because it accompanied these slide shows that my dad took. When you’ve lived with that and grown up with it, it’s the version of the truth of your family that you know. And when you introduce someone new into the family - like your brand-new husband - he’s thinking, Oh my God, this is the strangest, craziest story I’ve ever witnessed. And when he realized how much had been left out of my life by not having my brother there, I think that’s when he said, “We should see if we could do this.”

The motivation wasn’t like, I’m going to go and write about finding this camper of my childhood. The most conscious thing, I think, was the feeling that I needed to say good-bye. Because I didn’t get to do that. I was a kid and any tragic, accidental death - as we all now know – leaves you with that sense of “I wasn’t prepared.” Not that you could ever be prepared. By the time we retraced the journey and get all the way to the end, it hit me that it wasn’t about saying good-bye to my brother, it was to understand that he was with me all along. I think that’s the deepest take-away from the book: when you love somebody and they’re part of your family they don’t disappear. It’s not so much about letting them go, but about realizing how much they’re still a part of you. They’re in your blood and your soul and your heart and your memories. Even though he was just a child, his person formed our family. I think it took this search to find a way to say good-bye to realize that he was there all along.

The motivation wasn’t like, I’m going to go and write about finding this camper of my childhood. The most conscious thing, I think, was the feeling that I needed to say good-bye. Because I didn’t get to do that. I was a kid and any tragic, accidental death - as we all now know – leaves you with that sense of “I wasn’t prepared.” Not that you could ever be prepared. By the time we retraced the journey and get all the way to the end, it hit me that it wasn’t about saying good-bye to my brother, it was to understand that he was with me all along. I think that’s the deepest take-away from the book: when you love somebody and they’re part of your family they don’t disappear. It’s not so much about letting them go, but about realizing how much they’re still a part of you. They’re in your blood and your soul and your heart and your memories. Even though he was just a child, his person formed our family. I think it took this search to find a way to say good-bye to realize that he was there all along.

Mark Shaffer: The title, The Drive, is a huge understatement. How many miles and how many countries?

TB:13 countries and about 17,000 miles. If you factor in the first trip, it’s quite a few miles, that drive. (Laughs) Yeah, it’s a road trip.

MS: And it’s Latin America. Parts were dicey enough when you and Gary set out, but back in the early 70’s “dicey” was a gross understatement. Your parents and two little girls set off into the unknown in this hulking homemade camper that weighed, what, 14,000 pounds?

TB: Yeah. And if you know anything about campers that’ about 12,000 pounds too many.

(Laughter)

MS: Both trips presented some very serious situations.

TB: It’s strange. When my parents started off in 1973 they knew next to nothing about the Pan American Highway. There was a National Geographic article that my dad read. My parents didn’t speak Spanish, they’d never traveled there, they didn’t follow politics, they had no idea that students were being “disappeared” in Mexico or that there was a civil war in Guatemala wiping out the indigenous population. They had no idea.

For the second trip, I over-prepared. I read everything there was to know. I went to the Library of Congress and stalked every newspaper article about every country. And it made me feel like I could control this, I could figure out where to avoid. But in the end the only place that we decided to avoid was Columbia, which ironically was totally safe when they were there and not safe when we were passing through. Which was a real heartbreak because I remember that vividly as a kid. That country and Venezuela were among my parents’ favorites; the slide show stars. There were these incredible mountains and jungles and water and food. It was a high point. But it wasn’t worth [the risk].

MS: You could subtitle one of the early chapters “Gary Goes All In.”

TB: (Laughs) Yeah. Gary could convince me of anything.

MS: You’re newlyweds, have successful careers in D.C. and a nice house on Capitol Hill and you chuck it all to do this thing. You decide to do it in a similar, but more practical fashion with a retro-fitted vintage camper. But you also repeated one of you dad’s biggest mistakes.

TB: Yes. I’d say it was the only bad decision of the trip. Because I’d over-prepared and read all of this negative stuff, and recalling some of the things that happened on the first trip, I got so paranoid I decided to buy a gun. As a DC resident, I couldn’t, so I convinced my poor father-in-law in Wisconsin to do it for me. And it was literally an albatross around my neck through 13 countries. It made me physically ill from the worry and the guilt and the fear that if it was discovered Gary would be thrown in jail – because they would’ve assumed it was his. I’m not the kind of traveler who thinks everyone’s out to rob or murder me, but having that gun almost made me into that person. There’s a part of the book in Guatemala where I go for the gun because I’m terrified of something - something ridiculous, as it turned out.

TB: Yes. I’d say it was the only bad decision of the trip. Because I’d over-prepared and read all of this negative stuff, and recalling some of the things that happened on the first trip, I got so paranoid I decided to buy a gun. As a DC resident, I couldn’t, so I convinced my poor father-in-law in Wisconsin to do it for me. And it was literally an albatross around my neck through 13 countries. It made me physically ill from the worry and the guilt and the fear that if it was discovered Gary would be thrown in jail – because they would’ve assumed it was his. I’m not the kind of traveler who thinks everyone’s out to rob or murder me, but having that gun almost made me into that person. There’s a part of the book in Guatemala where I go for the gun because I’m terrified of something - something ridiculous, as it turned out.

MS: You’re the only person I know who’s pulled a gun on an earthquake.

TB: You can’t shoot earthquakes. The topper is that Gary tried to chase it off with a broomstick.

(Laughter)

But by the time we got to Nicaragua and had guns fired over our camper in the middle of the night in Sandinista country, I’d come to my senses. I’m not going to let it steal the whole trip from me. That was a big relief, but I still had the damn thing and couldn’t get rid of it.

MS: All the opportunities you had to just drop it in a river in the middle of a jungle, why didn’t  you?

you?

TB: I guess it didn’t occur to me until we got to the Beagle Channel. I guess I was still thinking, maybe, maybe, maybe. It was kind of a conundrum. But at that point we figured, why not toss it in and let it rust away into obscurity?

MS: Your road map was your mother’s journal from the first trip. She was a bit cryptic.

TB: (Laughs) Very.

MS: Even so, you were able to connect the dots on the map and also reconnect with people who you knew as a child. Some of my favorite moments in the book come from these remarkable individuals.

TB: Me, too. That changed the whole trip. It became richer. Everyone has so many sides and my parents were only able to see one side because they were still dealing with grief. So, they accepted the help of these good Samaritans and moved on and never wanted to think about it again. Those were the lowest moments of that trip, when really bad things happened: I had malaria, my sister had her face smashed in. My parents had no interest in maintaining any of those relationships or ever reaching out to them. But going back was great. I was able to say,”Thank you.” And I had no idea how worried they were about my family. We were this American family in a camper and there simply were no American families in campers in Latin America in 1973. They didn’t think we’d make it. And I didn’t realize how much of an impact our destitution had made on these kind angels along the way.

MS: Many of them had suffered hardships and losses of their own in the interim.

TB: One of my favorite parts is the dentist in El Salvador.

MS: Mine, too.

TB: When he asks me to take a piece of his [late wife’s] jewelry with me, it’s the last line in that chapter: “In that gesture is all the sweetness of El Salvador.” Finding these people gets you past the wars, the poverty and the headlines and it shows you that we’re all the same. Same with the woman in Bolivia. It was a country erupting by the time we were there but, yet she had this grace and explains that all anybody wants is a little kindness and that is what made this trip special for me - not necessarily finding the camper and all that. Those people made it important.

MS: Had things not turned out the way they did, how would that have affected you?

TB: You know, by Ecuador we figured it’s not going to happen. But by then we didn’t really care. I mean we wanted to find it, but these interactions were what was real and important and we had begun to realize that by then.

TB: You know, by Ecuador we figured it’s not going to happen. But by then we didn’t really care. I mean we wanted to find it, but these interactions were what was real and important and we had begun to realize that by then.

MS: In the end, you literally discovered the blueprints for what could have been your life.

TB: That’s when I realized how strong my mother had been when we’re looking at the plans my dad had to build a homestead [in Bolivia]. It would’ve changed our future. We would’ve never had the experiences we’d had and then to realize how strong my mom was to put her foot down after 61 breakdowns and all those miles was a revelation.

MS: It’s a very cinematic story. As a screenwriter, have you given that any thought?

TB: Yeah. It would be a difficult film to make because there are so many locations, but I’d love to take a stab at it. It would be a beautiful movie, the locations would be amazing.

MS: Who plays Gary?

TB: Hmm. I’m not sure. But I think Scarlett Johannson should play me.

(Laughter)

MS: Gary’s photos set the chapters up beautifully.

TB: I think very visually and his photos were the cues that brought it all back and helped me feel it and smell it all over again.

“If I could fill my life with paintings of the way the land arches to meet the convergence of clouds in a Patagonian steppe, I would never need windows.” – From The Drive

MS: How cathartic was writing this?

TB: The interesting part was discovering the truth of memory. I had this slide show memory of our history - my dad literally put on slide shows along with stories of the adventures. And yet, I saw in those photos my terrified mother. I’m a walking skeleton, and reading entries from my mother’s journal like, “I think we’ve had it” - utter desperation. The catharsis was the trip itself.

TB: The interesting part was discovering the truth of memory. I had this slide show memory of our history - my dad literally put on slide shows along with stories of the adventures. And yet, I saw in those photos my terrified mother. I’m a walking skeleton, and reading entries from my mother’s journal like, “I think we’ve had it” - utter desperation. The catharsis was the trip itself.

There was a moment in Peru near where my mom wrote that entry that I realized the reason I’ve tried to control everything my whole life is that I wasn’t able to control anything when I was seven. The whole world turned on its head. Everything bad happened on this trip and no one could fix it, so I felt like I had to. I had to control things. That was a moment of revelation at 15,000 feet. But you can’t control when people are going to leave. You can’t control what’s going to happen. You can only control how it’s going to change you. And ultimately that’s very freeing to be taught a huge road trip lesson which is like, “Yeah, your plans? Not a bit of difference to the powers that be.”

DRIVE ON

Join author Teresa Bruce and photographer Gary Geboy for a special presentation on The Drive, 5:30 - 7:30 August 9th at NeverMore Books 702 Craven St. Downtown Beaufort.

Take The Drive online at www.teresabrucebooks.com and ride along on the daily blog at teresabruce.me. On Facebook it’s The Drive – by Teresa Bruce and Twitter is @writerteresa